Lamplight City‘s Murder Mystery Is a Backdrop for an Exploration of Racial and Sexual Discrimination

Games Features Lamplight City

In the first full case in Lamplight City, a woman named Madam Duprée almost dies by being buried alive. Doctors thought she died from cardiac arrest days prior to her funeral, but when they heard a knock coming from inside her casket, they were shocked to find she was very much alive. The prime suspect, Albert Martin, is a Black man who is accused of using voodoo to put Duprée in a trance. As the case continues, it’s revealed that Duprée, a white woman, isn’t exactly an innocent person, as she mistreats and abuses her Black servants. As the culprit of the crime is revealed, the player must decide whether Duprée’s own racism outweigh the crime against her.

Lamplight City is a murder mystery, and as such it runs the risk of falling into classic murder tropes. Even when it does, it attempts to turn them on their heads. It addresses the discrimination women faced in pursuing math and science; it highlights the common struggle of Black people in a world that still considers them to be the Other; and it focuses on the life of people in the LGBTQ community who must hide their sexuality to not be harassed, or worse. The game isn’t afraid to show any of these hardships, and it’s a great game because of it.

Set in 1844, Lamplight City works to highlight the racial and sexual discrimination prevalent during the time. But the game doesn’t present examples of racism or sexism without making a statement about them. It doesn’t shrug it as a thing of its time; rather, Lamplight City uses those uncomfortable moments to show the horrors of bad people. It’s unfortunate that someone was almost killed by being interred, but how sad is it when the attack was in retaliation for the many people she’s harmed in the past?

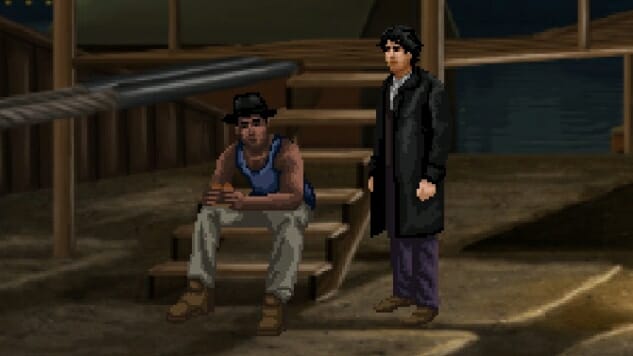

Miles Fordham, the private investigator and main character of the game, is white, but his wife Adelaide is a Black woman working as a hairdresser. Adelaide isn’t a detective, yet she helps her husband in many ways throughout the game. Interestingly, when she does aid Miles during his investigation, she’s often accused to being up to no good. For example, Miles asks his wife to persuade an officer to leave his station, but when she goes and tries to flirt, the officer assumes she’s trying to lure him to an ally to be mugged by “a gang of sambos.” Miles punches the officer in anger. It’s not often that a game allows a puzzle to be solved by punching a racist.

Even when Lamplight City does fall into unfortunate tropes, it still tries to complicate them. Miles’s partner, William Leger, is gay. He hints early in the game that people dislike him and Miles because of their friendship. William, though, is the very first person to die in the game. Killing off LGBTQ characters is an old trope known as “Bury Your Gays.”

Yet, in death, William is ever-present. Even with his body gone, he continues to be Miles’s partner as a narrator. Despite his death, William is still a prominent character within the game. Further, he isn’t murdered because of his sexuality, but rather his involvement as a detective on a crime scene. It’s an interesting spin on a narrative stereotype. Importantly, there are LGBTQ characters, as well as Black characters, who do survive, who are not murdered because of discrimination.

Still, there’s something to be said about the main character being a white, heterosexual man. The help he receives come from people of different genders, sexualities and races, but Miles himself falls right into the classic detective image. Again, Miles complicates the trope as he actively seeks the help of those around him. He recognizes racism and sexism and tries to right those wrongs, but doesn’t stop to address his own privilege.

Lamplight City is aptly named, because it’s a game all about shining a light on the horrors of everyday life. As a point-and-click adventure, it looks like an old take on mystery games, but instead it looks into finding justice in the world’s acts of terror against minoritized people. Its strength is how it challenges tropes, and while it may not always be completely successful, it’s a game that knows exactly what’s wrong with mystery stories, and knows how to fix them.

Shonté Daniels is a poet who occasionally writes about games. Her games writing has appeared in Kill Screen, Motherboard, Waypoint and elsewhere. Her poetry can be seen at Puerto del Sol, Baltimore Review, Phoebe, and others literary journals. Check out Shonte-Daniels.com for a full archive, or follow her for sporadic tweeting.