Spoiler warning: This thing has spoilers. So we’re warning you about them. Don’t read if you haven’t played Tacoma or don’t want to know what happens in it.

Fullbright likes misdirection. Like Gone Home, the developer’s new game Tacoma plays with our assumptions about a well-defined gaming genre. Instead of horror, though, Tacoma tackles sci-fi, with a familiar setup: a solitary figure approaching an abandoned space station to figure out what happened to the workers who used to live there. Instead of aliens what you find are the fragments of regular lives lived in an irregular environment, lives dictated and defined by the work and the employer that sustains them. What you find is a metaphor for how we let work isolate and suffocate us.

As soon as you start getting to know the six workers who were stationed on the Tacoma you learn about the toll this job takes on their personal lives. They all have family they’ve had to leave back on Earth during the length of their assignment. A few of them have seen their romantic lives reshaped around the limits of the job, from makeshift relationships forged on the Tacoma out of loneliness more than anything else, to one staffer who accepted a limiting and less lucrative position because her lover and coworker couldn’t get a better assignment anywhere else. One worker is so closed off to her coworkers that her closest relationship is with the ship’s AI, ODIN, who, despite being a disembodied robot voice programmed with artificial emotions, is clearly working hard to win her over.

Early on you’ll come across the word Loyalty, capitalized as such, in emails you hack into and conversations you eavesdrop on. You’ll learn that by 2088, the year the game is set in, this concept defines labor. Instead of retirement plans or 401(k)s, workers build up Loyalty the longer they work with a company. In the story of one worker on the Tacoma you’ll see what happens when somebody isn’t loyal to a company: after graduating from Hilton University (because businesses directly own the schools in the future) he leaves the company for one of its competitors, Carnival. (Yes, the cruise line.) Later he leaves Carnival for Venturis Corporation, the fictional company that owns the Tacoma. Throughout his private quarters and office you can find rejection notices from all three companies, informing him that despite his knowledge and experience they wouldn’t hire or promote him due to his lack of Loyalty. He was expected to stay with Hilton for the length of his career, all on the promise that the company would be loyal to him when he was no longer able to work.

Here are the spoilers: of course the company isn’t loyal to the workers. In time you find out the “accident” that stranded them on the Tacoma was staged. Venturis hoped to sacrifice them in a planned disaster to help out its bottom line. The workers’ livelihoods would be destroyed if they weren’t loyal enough to the company, while the company plans on destroying their very lives for its own possible gain.

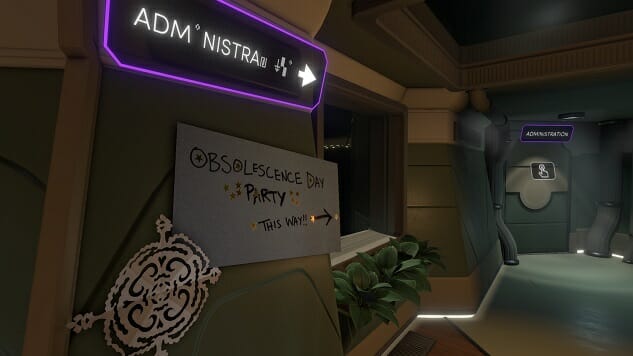

Tacoma’s critique of capitalism is far from subtle. The owner of the Tacoma wants to murder its crew, literally subordinating their existence to the company’s business. The six staffers on the Tacoma are established as disposable in the eyes of their employer early on, when you learn that the only reason they’re even on the space station and weren’t all replaced by artificial intelligence is because of a legal victory won by a union. (The fact that human workers were legally barred from being made obsolete is celebrated as a holiday.) Six is the smallest number of employees that can be legally assigned to a station the size of the Tacoma, and so there are exactly six crew members. Perhaps if companies like Venturis hadn’t fought to cut the workforce as drastically as possible the emotional and mental weight of being isolated in space wouldn’t impact the Tacoma’s crew as acutely as it does.

This all resonates in part because of the medium in which it’s relayed. Venturis’s plan was to suffocate the workers on the Tacoma after cutting them off from their families and loved ones. In Tacoma you can find clear echoes of the horror stories about “crunch time,” the videogame industry term for when designers are expected to work excessive hours every day to meet a project’s schedule, often going days without spending time with their families. After weeks or months of isolation, the workers who suffered through crunch time are often summarily let go once a project ends. Videogame publishers and developers demand almost everything from its designers, and then show them little loyalty in return.

Tacoma might present itself as science fiction. It’s set in a shiny, futuristic space station, with each window a beautiful vista of black and pinpricks of light. But like all good sci-fi, it’s focused squarely on the present. Its depiction of exploitative labor practices and the one-sided relationship between employers and employees, of the marginalization of the worker, might be set near the end of the century, but its message is as current as videogames get.

Garrett Martin edits Paste’s games, comedy and wrestling sections. He’s on Twitter @grmartin.