The current surge in interest in better boardgames (German-style, Euro, whatever you want to call them) has led some of the biggest publishers to bring back titles that had fallen out of print or were just in need of a refresh. Two very highly-regarded games are now out in brand-new editions, Reiner Knizia’s Ra and Uwe Rosenberg’s Agricola. A review of the new edition of Ra ran earlier this month; now here’s a review of Agricola.

Agricola is an absolute behemoth in the Eurogame segment; after Settlers of Catan, there might not be another game that’s had as much influence on game development as Agricola has. Uwe Rosenberg’s unlikely hit—currently ranked 8th in Boardgamegeek’s all-time rankings, after a lengthy spell at #1—has inspired many other games that almost brag of their long playing times while ushering in a whole subgenre of games with rulebooks that resemble Russian literature. Yet of the many games that have followed in Agricola’s wake, none has quite captured the magic of the original, which manages to take an incredibly humble theme and a lengthy set of rules and make it somehow very fun.

This new edition of Agricola includes a suggested “junior” way to play that omits the cards that form the heart of the full game and give it many layers of complexity. This introductory game is ideal for younger players or folks who are new to the game as a whole and might be intimidated by learning the game and the mechanic of the cards at the same time. (Or who might play his first game with the full rule set against someone experienced and get absolutely trounced in the process. I’m looking at you, Tim.)

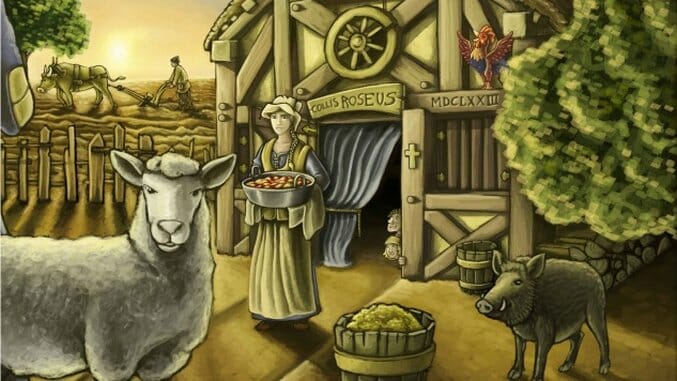

Agricola players are farmers who must feed their families first and foremost, and while doing that, try to build out their farmsteads by plowing fields, planting crops, and rearing animals. A player starts with two family members (oversized meeples in this new edition), and may gain up to three more over the course of the game. The game consists of fourteen rounds, and in one round each player may place each of his/her meeples somewhere on the board to undertake an action. A space occupied by one meeple is then off-limits to other players for the rest of that round, unless another player has a card that invalidates that rule, so there’s a strategy in when and where to place your farmers. The constant battle over the course of the game, however, is between acquiring resources for right now that let you feed your family—there are six harvests at which you must have at least two food tokens per adult family member plus one per baby (new in that round)—and building out your farm to produce more stuff as the game progresses.

The cards are what make the game such a great intellectual challenge, turning something that’s a bit like work into a massive puzzle that involves other players and an internal clock. Players start the game with seven cards that, once played, grant the player certain extra skills, privileges, shortcuts, resources, or something else—but the point is that you tailor your strategy to the cards you play, so every game ends up quite different. This concept, layering skill cards on top of a basic game of worker placement, has become one of the most common underlying structures in Euro games, and you can see Rosenberg’s influence in games as far afield as Seasons, Bruges, and Discoveries.

This new edition has several substantial changes from the previous versions of the game, all done in concert with Rosenberg and the new publishers, Lookout Games and Mayfair Games. The main box only includes components for up to four players; a separate expansion for 5-6 players will come later this year. The old colored cubes for sheep, cows, and boar are replaced by wooden pieces that look like actual animals. The cards have changed, as Rosenberg has tossed some cards he found were too weak or seldom used, replacing them with “power” cards from expansions to the original game. A few space names have changed as well. The rule book is now two documents, with the appendix printed separately, reducing the intimidation factor of the original’s mammoth tome. One benefit of these changes is a reduction in the game’s MSRP by a sawbuck to $60, still on the high end for boardgames, but justified given the game’s components, complexity, and very high replay value.

I tried the card-free version to introduce my daughter to the game, and she surprised me somewhat by saying she liked the game and wanted to play again. She enjoyed planning ahead and appreciated the fact that she’d be rewarded for doing lots of different things—you can lose a point at the end of the game if you end up without any of the five main food resources, or if you can’t feed your family, or if you don’t develop your whole farm. She wanted to try everything anyway, so a scoring system that rewards that actually works well for her sense of fun. Our game took about an hour if you factor out time I spent explaining the game to her. A full game with three or four players using the cards would likely take about two hours, more if this is adult game night and the various farmers decide to bring a little moonshine to the mix. I’d consider this an essential title in any serious boardgamer’s collection, even if you might find the gameplay daunting at first glance.

Keith Law is a senior baseball writer for ESPN.com and an analyst on ESPN’s Baseball Tonight. You can read his baseball content at search.espn.go.com/keith-law and his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.