On-Gaku: Our Sound Is a Beautiful Portrait of the Power of Music

Being a teenager in a suburban town can be excruciatingly boring. Fun has to be found even when there’s nothing to do, which often manifests in dangerous and downright stupid behavior (we, for example, drove down unlit streets without headlights on as fast as we could just to feel something). This boredom also leads to bone-crushing depression. With no variety in routine, everything feels useless. But then, sometimes, something appears that banishes that monotony and breathes excitement into an otherwise dull existence. That discovery can be revelatory; life can suddenly have purpose. In the case of the trio of delinquents in Kenji Iwaisawa’s incredible debut feature, the animated On-Gaku: Our Sound, they discover the catharsis and power of music.

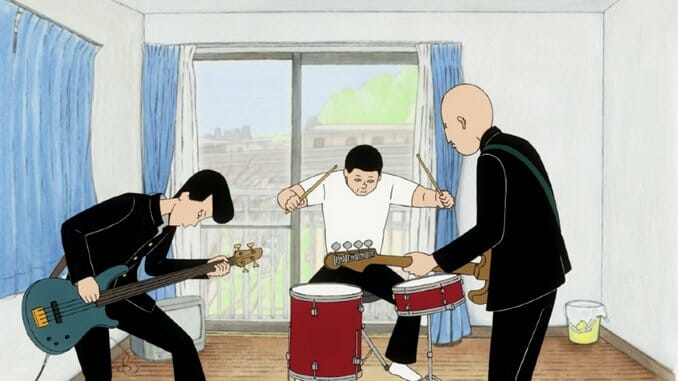

Kenji (Shintarô Sakamoto), Ota (Tomoya Maeno) and Asakura (Tateto Serizawa) spend their days either playing videogames in a secluded classroom or looking for fights with other high schoolers. With nothing else to do, they turn to violence to get their kicks, which has earned them a reputation of being delinquents. But, one day, Kenji decides he wants to start a band. None of them have experience, but that doesn’t matter; this is finally something exciting that will break the monotony of their lives. So with two basses and an incomplete drum set, they write a song. It is a simple one-note bassline, but it awakens something within them. They have finally found joy.

On-Gaku: Our Sound is writer/director Iwaisawa’s love letter both to the power of music and to the manga of the same name by Hiroyuki Ohashi. He took inspiration from Ohashi’s simple and sketchy style and hand-drew almost every single frame of the film himself. His characters are very basic, with short lines making up faces and bodies with no extensive shading or coloring. These initial character designs are building blocks for the masterpiece Iwaisawa is working towards. His backgrounds are much more detailed and full of color, looking like elaborate watercolor paintings that Kenji and crew are merely strolling through. This tension between simple characters and painstakingly constructed backdrops hints at something coming, that there is something more to these literally two-dimensional teens. The potential for beauty is lurking underneath the surface, and when it finally makes itself seen, it is breathtaking.

As the trio pick up their instruments and finally play a note at the same time, the animation shifts into rotoscoping, where Iwaisawa has traced over actual footage to give these characters the appearance of life-like movement. The camera goes from stagnant to kinetic as it moves around the boys who are experiencing something special with a single strum of the strings and bang of the drum. Kenji even grumbles, “That felt good.” Iwaisawa is purposeful with his style, using it not to create something flashy but to create a deep emotional connection to the freedom Kenji, Ota and Asakura have suddenly discovered with music. As the film progresses through more musical numbers, Iwaisawa continues to experiment with form as certain songs evoke different emotions from his characters, whether it is a kindly folk song or a primitive-feeling rocker that reverberates in a listener’s chest.