Phone Booth‘s Obsolescence Works To Its Thrilling Advantage

Stumbling upon a public phone in 2023 is like finding a fossil in a sandbox: You’re looking at a relic of a bygone era, tucked away in its ecosystem’s stratum. It doesn’t serve a purpose. It’s there to complement the terroir. Surprisingly, the phone booth’s status as yesterday’s bric-a-brac doesn’t affect Phone Booth, Joel Schumacher’s 2003 psych-thriller, set in and around a New York City call box. Where phone booths are pitiable and obsolete, Phone Booth is taut, sweaty and layered with the post-9/11 paranoia that bled into American cinema throughout the decade; if anything, the obsolescence is to the film’s advantage.

The grinding advance of industry crushes the old to make way for the new. It’s the capitalist way! We ditched cassette tapes for CDs, and CDs for MP3s; VHS for DVDs, and DVDs for Blu-rays and 4Ks; floppy disks for CD-ROMs; faxes for emails. But no commodity switcheroo has had the same social and cultural impact as the smartphone, at whose altar all other phones–rotary phones, dumb phones, landlines–have been sacrificed. Whether iPhones and Galaxies improve our lives is an argument without end. One day, we curse our handheld computers for giving everyone, strangers, friends and especially our parents, unfettered access to us; the next, we’re doomscrolling on Instagram and zoning out on Dungeons of Dreadrock.

Regardless, time’s passage has rendered the smartphone’s predecessors quaint, and opportunities to see antediluvian phone models in the wild are rare. That goes for phone booths, too. Once an essential public good, they’re now largely blinked from existence. Today, Phone Booth, a movie that met with modest scrutiny on release for both being too thin and too heavy-handed, is a reminder of how people used to communicate with each other from a distance, filtered into a singular chamber piece. But the film isn’t quaint at all. It’s nerve-wracking.

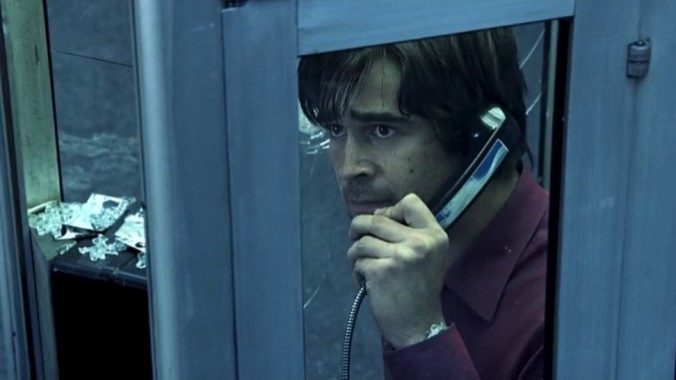

Stuart (Colin Farrell), a PR scumbag greased up with self-absorption, makes a pit stop at a Times Square phone booth; he’s calling his mistress, Pam (Katie Holmes), while his wife, Kelly (Radha Mitchell), is none the wiser. He hangs up. The phone calls back. It’s a man, credited as the Caller (Kiefer Sutherland), who instructs Stuart not to leave the booth under penalty of death. Stuart doesn’t buy the “death” bit, but the Caller gives him a taste of his skills as a crack shot; he knows all about Pam and Kelly, too, enough that Stuart knows the guy means business. When a pimp tries to bust into the booth, this intimate hostage situation blossoms into a murder party. Everyone’s invited, too: Pam, Kelly and Ed Ramey (Forest Whitaker), a police captain on the scene, gulled by the Caller into believing Stuart to be dangerous.

Schumacher’s script is authored by genre legend Larry Cohen, whose 1976 sci-fi-horror-crime procedural God Told Me To feels like Phone Booth’s distant cousin; Both movies orbit killing sprees committed by people who claim a higher calling, though not necessarily a higher power. The various murderers in God Told Me To recite the film’s title when pressed about their motives. They do what they do at the Lord Almighty’s command, lambs heeding their shepherd. The Caller has an actual mission: forcing dishonest men to turn over new leaves, by any means necessary. “You don’t have to thank me, nobody ever does,” he tells a terrified Stuart in their parting exchange. “I just hope your newfound honesty lasts. Because if it doesn’t, you’ll be hearing from me.” Cohen doesn’t give the Caller an explicitly Christian background. He’s just a moralist with goals, plus a really big sniper rifle.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-