In Spite of the Cannes Controversy, Netflix Isn’t Committing Cinematic Heresy

Netflix isn’t a threat to cinema, it’s simply providing healthy competition

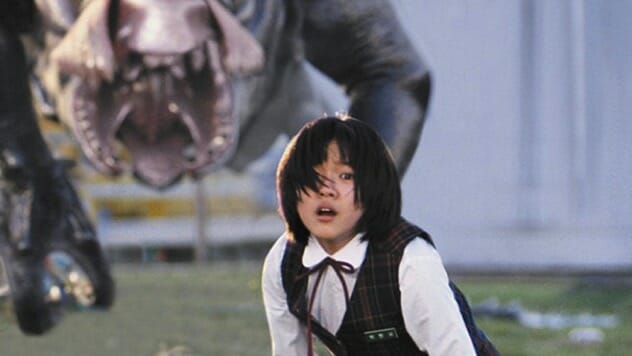

Drowning out the usual palaver—prizes were handed out, deals were made, hideous posters for upcoming movies were unveiled —the biggest story out of Cannes this year was the Netflix controversy. The two movies that Ted Sarandos brought to the Croisette—Bong Joon-ho’s monster movie-cum-capitalist satire Okja and Noah Baumbach’s familial comedy-drama The Meyerowitz Stories—suffered a cool reception before they even played. Audience members booed when the Netflix logo appeared in the films’ opening credits, while prior to their screening 2017 jury president Pedro Almodovar hinted that he wouldn’t even be considering handing out awards to any Netflix productions.

For Almodovar, echoing the sentiments of the French film industry, platforms such as Netflix, while “enriching,” “should not take the place of existing forms like movie theaters.” The implication by the Cannes faithful, above all, has been that Netflix is a threat not just to the existing business model of cinema, but to the purity of the medium itself. In the future, new rules might bar any Netflix movies from appearing at Cannes again. The festival reiterated a commitment to a “traditional mode of exhibition of cinema,” as Netflix went on to play there for the first and potentially last time.

Change is always jarring, and of course film-lovers will appreciate what Almodovar has called “the capacity of hypnosis of the large screen.” But cinema has not just been about the theater experience for some time, distributors have been experimenting with all kinds of different release strategies for years, and Netflix reaching almost 100 million subscribers hasn’t stopped people from going to the theater altogether (though attendance is down in the US, it’s up in Europe). No matter what rules Cannes enforces, change has come, but contrary to how Almodovar and co. see it, home streaming is coming to co-exist with theatergoing—people pay for access to Netflix, as they continue to pay for entry into the cinema.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-