Many films this year have been especially willing to offer in-depth cinematic explorations of high-profile tragedies that have already been covered in the public sphere, though whether there is any purpose in that is a singular question that should be put to the director of each. Ideas of intent and purpose have swirled around fictional films like Dark Night, Deepwater Horizon, the upcoming Patriot’s Day, and needled-at documentaries like Kate Plays Christine and Amanda Knox. Kim A. Snyder’s documentary, Newtown, is no different. Though it hardly ever feels like it’s exploitative, it’s nonetheless subject to the same question of existence.

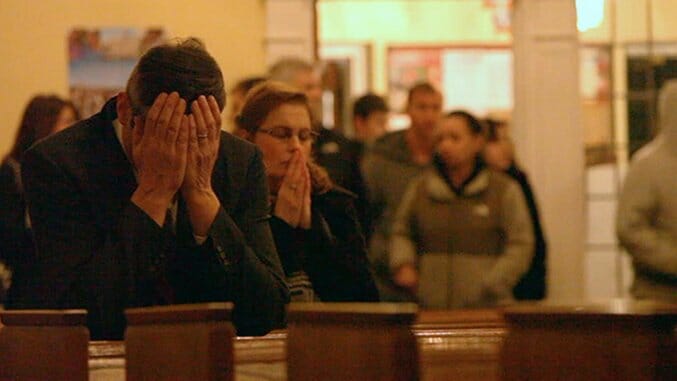

Newtown is a well-meaning, deeply humane film, a snapshot into the day-to-day trials of those affected by the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, where a gunman murdered 20 children and six adults. But it’s also a film that’s more about watching victims find personal catharsis than providing viewers with insight into what that’s like. That’s not to say that there aren’t illuminating, powerful moments in following these peoples’ lives, just that Newtown can’t inevitably focus on whether it’s an issue documentary, memorial or intimate procedural.

The first third of the film presents an immersive experience as it traces the circumstances of the shooting through an interconnected web of witnesses ranging from parents who lost children to EMTs who were scarred by their experiences that day. This format is short-lived, even as these early interviews lead to some of the film’s most goosebumps-inducing moments, such as a surviving teacher remembering how a few of her students were stifling nervous laughter during the shootout, or an EMT speaking about seeing waves of children arrive in ambulances at the hospital.

From there, the film considerably expands its ambitions as Snyder and her crew follow a few select subjects into their private spaces to watch them cope with their scars. With aerial photography, home video and present-day interviews, these scenes attempt to delve into the shared headspace of people in this community. They’re not only the most effective scenes, but some of the only parts when the film feels like it’s transcending material that could be gleaned from news footage or interviews. Interviews are filled with small, everyday details that just wouldn’t come up in a 20-minute interview with a reporter, and Snyder uses these details to create a larger portrait of loss.

There are few ways to better evoke the totality of the victims’ grief than Francie Wheeler admitting that she can’t stop signing cards as Ben’s spirit, her way of remembering her son—or her husband talking about how he struggles to find beauty in the chaos of the universe in the aftermath of the shooting. In these moments, the film seems to know exactly what it is and what it’s doing, helping to untangle these people’s struggle to find closure.

Such scenes don’t really represent the film as a whole, though. Newtown’s approach is all-encompassing, touching on many different subjects: the tight-knit community, the complicated relationship between survivors and those who lost someone, the behavioral shorthand that comes with grief, and, especially, the legislative crusade to change gun control laws. It’s admirable that the film attempts to show such a multi-faceted view of the community and the effects of the tragedy, but it ends up feeling deeply rushed.

In particular, the material that revolves around the survivors’ attempts to persuade legislators only underlines an unfocused structure. This isn’t trying to be Bowling For Columbine, but there’s still a very muddled quality to how Newtown presents the near-futility in pushing regulations related to assault weapons. To be fair, the attempt was a political failure, which may explain why it’s introduced and nearly as quickly discarded, but it still points to the film’s overall lumpiness.

It becomes even more difficult to reconcile these scenes in Washington when they’re placed in the third act at a seemingly climactic moment, only for the film to go on for nearly 15 more minutes. At its best, there’s a bracing forward momentum to the stories of the survivors and their attempts to move forward, but those scenes are placed in a film that can never quite decide what it’s trying to accomplish. Early in Newtown, Bill Cairo, a state trooper, deigns to go into further detail about what he saw in the Sandy Hook classrooms. “Emotionally, [people] need to know, graphically they don’t,” he says, speaking to the outside perception of the shootings.

His words are an encapsulation of human beings’ natural impulse to learn more about even the most vile circumstances, but the quote also unexpectedly serves as a challenge to the film’s intentions. Newtown is a stirring reminder that life goes on, even when the foundation of one’s life is shaken by an event, but when it tries to cover too much, the film invites more questions than it explores.

Director: Kim A. Snyder

Release Date: October 7, 2016