The Hero’s Road Trip

Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds, / many pains he suffered, heartsick on the open sea / fighting to save his life and bring his comrades home.

—The Odyssey, Fagles translation

This is not a story. It’s a road trip, which, same difference. In a good one, the start is exciting and the finish is satisfying and we end up somewhere else. Somewhere a long way from where we started.

—Alice Isn’t Dead, “Episode 1: Omelet”

Stories, said every one of my English teachers, tell you a lot about a culture. (Also, they said everything is sex.)

For instance, we know without even checking their IMDB profiles that the scriptwriters of The Wolverine were probably American, since we all got up in the middle of the theater and demanded a refund when the Japanese gangsters in it all suddenly pulled out automatic weapons in broad daylight in a country whose annual firearm deaths per capita are a rounding error.

(It wasn’t just me, right?)

The ancient Greek heroes who win are sneaky: Odysseus’s Trojan horse, Bellerophon’s judicious use of air superiority, Theseus’s ball of string in the labyrinth. The ancient Greek heroes who die are your mashers: Achilles meets his end by a dishonorable projectile weapon and Hercules—who never met a problem he couldn’t punch until it died—is killed by treachery.

It’s the scrappy, clever hero who is best equipped to wander through the weird purgatory of the unknown and actually make it back home intact, the Greeks figured. And why wouldn’t they think so? They were a seafaring culture, at the mercy of winds and tides that rewarded knowledge and judgment rather than main strength.

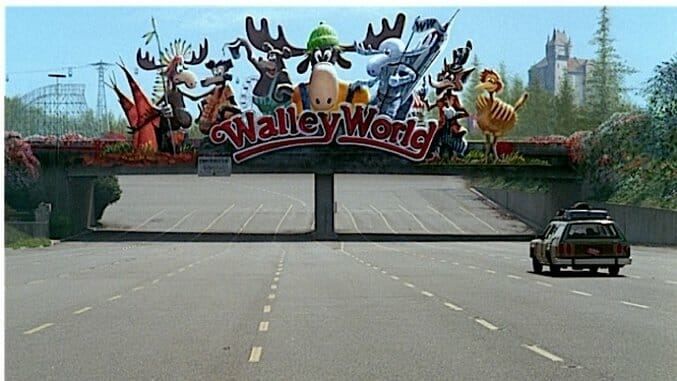

The United States is young yet, but she’s got her weird purgatory, too: the open roads of the Lower 48. It’s no coincidence that so many road trip movies are about a lot more than just getting from Point A to Point B.

The Known

In Fanboys (2009), Sam Huntington is as stifled by his position as assistant manager of a string of car dealerships as his childhood idol was by farm life on dusty Tatooine. Soon, he will be pulled on a cross-country road trip to steal a rough cut of Star Wars: Episode One, because this is 1999 and nobody knew it sucked yet.

The hero’s journey begins in “the known,” a mundane and inoffensive place where all the normal rules apply. It’s an even chance whether the hero prefers this or chomps at the bit to get away from it: Bilbo could’ve done without his trek to the Lonely Mountain, but Huckleberry Finn couldn’t get away from clean clothes and his unstable father fast enough.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-