The Ornithologist

There are times during João Pedro Rodrigues’s newest film, The Ornithologist, wherein you can’t tell if it’s all a big sexy joke or if it’s an earnest, religious and intellectual inquiry into the boundaries of spiritual and physical adventure. There’s enough evidence in the film—which follows a strapping studier of birds on his journey to note black storks and the various surreal things that occur to him—to argue that it’s both.

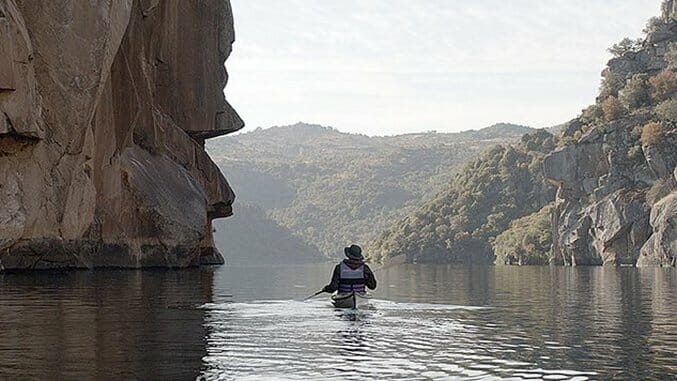

Fernando (Paul Hamy), our bird man, is over the course of the film: pissed on, tossed about by river waters in his kayak, badgered by a presumed lover from back home via text, without medicine, has the eyes on his passport photo burnt through, has sex with a twink deaf and mute twink named Jesus, and is tied up St. Sebastian-style by two lost Chinese lesbians on a religious pilgrimage. Rodrigues easily integrates an aesthetic reminiscent of a nature documentary into scenarios that, like a modern Portuguese take on “The Aristocrats,” mount in their ludicrousness. Yet, the oddball adventures that color Fernando’s journey seem embedded logically within the film’s universe, and even better, within Rodrigues’s own screenplay. However strange it may be to watch a Satanic ritual occur on screen, the director has seemingly mapped out precisely how to transition from weird scene to weird scene, making The Ornithologist and effectively coherent fever dream.

The film’s more explicitly theologically textured aspects are mired in Catholic mythos, with Fernando’s path and experiences riffing on those of Saint Anthony of Padua. The significance of this has less to do with its definitively scriptural allusions and more perhaps for its broadly symbolic ideas: St. Anthony is the patron saint of lost things, and while Fernando might be in search of black storks, a sense of loneliness bleeds into the film. Hamy has a gamely attitude throughout the film, but his movements—outwardly capable, especially in such outdoorsy contexts—still contain traces of melancholy. He ignores the texts from someone who cares about him, and he is in constant denial of the idea that this person (and perhaps on a macro scale, anyone) cares about him.

The prospect of a rescuer from the kayak incident that sets the film in motion does nothing to assuage this anxiety: the two wandering Chinese women who initially save Fernando’s life bind him in rope, and then consider castrating him in the name of St. James. Too, the encounter Fernando has with the sheep herder named Jesus (Xelo Cagiao) is marred by the wild suspicion that Fernando’s sweatshirt was stolen by the man. One gets the impression that with every shot Rodrigues positions through the binocular lens, and every reverse shot through the eyes of various aviary, Fernando looks for something in these creatures, something akin to the fulfillment or completion. Really, all he has is himself and the birds.