”What do children at play really look like? Not like this, as in movies. One should use binoculars… Only if this were a film would I consider it real.” – Werner Herzog, Of Walking in Ice

Toward the end of 1974, with The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, the German director’s fourth fiction feature, just starting its premiere run, Werner Herzog learned that his friend Lotte Eisner was close to death. Possessed by the belief that in walking from Berlin to Paris to see the French-German cultural luminary one last time he could somehow stall her demise, he left immediately, having obtained a decent pair of boots. (“My boots were so solid and new that I had confidence in them.”)

From November 23 through December 14, through white squalls and assorted apocalyptic farm weather, largely breaking into barns or villagers’ living rooms to sleep, occasionally thinking about his new movie playing in various places around Europe, Herzog walked. More than half the time he was desperate and freezing cold, and only on the odd morning was his belly not aching, but very rarely did he entertain the notion of giving up. At least that’s how he tells it: He published the journals he wrote while walking in 1978’s Of Walking in Ice, and he’s told this story, to various anecdotal ends, often, and one time to Jonathan Demme—as he does with many similarly strange and wonderful anecdotes, to the point that they’ve transubstantiated into uniquely Herzogian aphorisms, then tropes, then, inevitably, memes.

Another thing he makes blanket statements about—aiding, perhaps intentionally, in his inevitable complete memedom—is how much he can’t stand psychoanalysts, calling them quacks and looking for any opportunity to confuse them for psychiatrists, whom he also can’t stand. He’s said to Jimmy Kimmel once, if I remember correctly—maybe it was the other Jimmy—that he has trouble getting many people’s senses of humor because he can’t pick up on irony. He’s said that he never dreams, either. That he physically can’t. Doesn’t offer an explanation, just breathes it into being, another entry into the Herzogian canon he’s mostly built himself. We’re invited to ignore how often his films resemble unmitigated analyses of the psyches of dreamers, how funny those films can be, how incisively Herzog speaks through his films of their dreams. Most of all, how freely his films treat truth.

According to his journals, Herzog arrived in Paris, exhausted and his clothes barely hanging from his bones—though he’d arguably endured so much worse in the Peruvian jungle when filming Aguirre, the Wrath of God with Klaus Kinski some two years prior. In Of Walking in Ice’s final entry, he describes meeting Eisner, who wouldn’t die for nearly another decade, embarrassed his legs were in pain. Seeing how well she was doing, he wrote, “For one splendid, fleeting moment, something mellow flowed through my deadly tired body. I said, ‘Open the window. From these last days onward I can fly.’”

Or he just made that part up.

“The line between fiction and documentary doesn’t exist for me. My documentaries are often fiction in disguise. All my films, every one of them, take facts, characters and stories and play with them in the same way. I consider Fitzcarraldo to be my best documentary and Little Dieter Needs to Fly my best feature. They are both highly stylized and full of imagination.” – Werner Herzog, Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed – Conversations with Paul Cronin

Werner Herzog released Little Dieter Needs to Fly on October 2, 25 years ago, barely two years before he’d codify the phrase “ecstatic truth” in 1999’s “Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Filmmaking,” which he claims he wrote in 20 minutes in a Duluth hotel room.

The declaration, a 12-point approach to “non-fiction” film, really starts buzzing around number five: “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can only be reached through fabrication and imagination and stylisation.” As he later explains to Paul Cronin in Guide for the Perplexed (a book of interviews with Herzog that Herzog co-edited), “the fundamental idea behind [the declaration] is that we can never know what truth really is. The best we can do is approximate.”

So, in 1997, Herzog had sublime forgery on the mind. He’d written and directed 1995’s Gesualdo: Death for Five Voices, a docu-fictional musical travelogue through the life of Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa—renowned 16th century composer, Italian prince and rich maniac—in which he both wholesale imagines bleakly beautiful episodes from the prince’s life, and cajoles people in the street to do what he tells them because he has a camera. Still, Gesualdo reads as a documentary, and no one would suspect that Herzog asked academics to lie about their beloved subjects. Filled with oddness and curiosity and a luridly soothing tone, the film feels like Herzog has stumbled upon one fascinating chunk of the universe after another. All of it is connected simply because all of it shares in a Herzog film—which can sometimes feel like watching something elemental unfold. Whether Gesualdo gruesomely murdered his son or not (likely not), Herzog taps into the historical figure’s chaotic nature more essentially than a more faithful, less stylized biographical documentary ever could.

Herzog’s Dieter Dengler, the subject of Herzog-narrated Little Dieter Needs to Fly, is an ebullient German immigrant, a former test pilot pushing 60 years old who lives in a house he built himself in the mountains just north of San Francisco. Where most Bavarian children inherited trauma from WWII, little Dieter received the dream of flight as if beamed to him directly from God, having stared into the eyes, so he recalls it, of a bomber pilot during a routine payload dump in his village. His origin story already suffused with war and toil, Dengler moved to California following a lengthy indentured servitude to an abusive blacksmith. His goal was to enlist in the Navy and, hope upon hope, become an aviator. Following the requisite years of poverty and corporal shaming care of this nation’s armed forces, by 1966 Dengler finally earned his wings and was immediately shipped to Southeast Asia, where he was shot down over Laos within 40 minutes of his first bombing run.

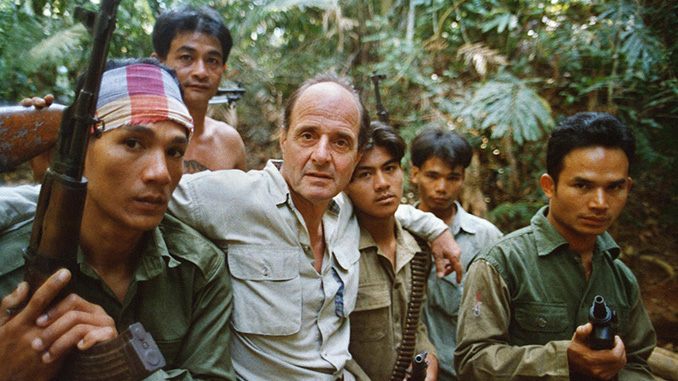

Herzog delights in the dopey military training videos and tales of Dengler’s early days in 1950s southern California, but the film’s real narrative meat is in Dengler’s retelling of his experience as a POW, first under the Pathet Lao and then the Viet Cong. Returning to the jungles of Laos and Thailand to retrace Dengler’s time as a prisoner, together the director and subject conscript a group of locals to help reenact the experience, Dengler retreading site after haunted site while telling the camera—held by Herzog’s frequent cinematographer, Peter Zietlinger—of his nearly seven months of starvation and torture, violence that seems at times even too macabre for Herzog to share.

As Herzog told Karen Beckman in 2007, “The motive of flight and of the need to fly appear quite many times in my movies: Little Dieter Needs to Fly was some sort of paradigmatic sort of title, yes, there is a man who needs to fly, but yet, like in an ancient Greek drama… you have a man and his dream, and punishment for the dream, and some sort of redemption.” The more Dengler re-lives his time in the jungle, trying to revisit the headspace of the horrors he witnessed, the more Herzog points out the difficulty of what they’re doing. “Of course Dieter knew it was a film, but all the old terror returned as if it were real,” Herzog narrates over a scene of Dengler tied and running between a swift group of locals playing his Laotian torturers. Dieter seems to respond to Herzog’s non-diegetic words, saying, “I told myself: ‘OK, play along with them. Running like this might chase the demons away.’” The tendency is to believe him: Rehearsing Dengler’s story this way helps bring the man catharsis. It might help him resolve the old nightmares in his head. It might provide some manner of redemption.

Herzog and the people who occupy his films obsess about dreams, but rarely about the complicated symbolism of dreams. More about the nature of dreaming, how dreaming transcends what seems possible. For all his reputation might suggest, Herzog is a pretty literal guide throughout his documentaries—or whatever you want to call them—and Dengler an archetypal Herzogian font of blunt oneiros. “This is basically what death looks like to me,” Dengler states, gesturing to an aquarium tank of white jellyfish, a detour from the film’s survival narrative. Zeitlinger’s lens lingers on the jellyfish and the most seductively exoticized music you’ve never heard before—that Shazam will not recognize—adds just the right whisper of not-quite-real. And when Dengler says it, it sounds slightly over-fussed-over, excused maybe because, like Herzog, he has a very mannered accent. He sounds as if he chooses his words carefully, but also as if these aren’t his words. Herzog loves that shit. Later he told Paul Cronin, “These ethereal, almost unreal creatures express his dreams perfectly, though it was all my idea.”

Between a litany of misery and a rousing yarn propelled by the indomitable human spirit, Little Dieter Needs to Fly moves like an unbelievable war adventure. But we believe what Dengler tells us because the documentary form demands that of us. Likewise, Herzog, the documentarian, assures us of Dengler’s veracity through the sincere act of affording him this film. We deny it as exploitation, because we’re never quite sure where fiction bleeds into documentary, or vice versa, as if the fictionalized characters of his films—real or made up or bits of both—know that one day, with intense sympathy for their unexplainable plight, Herzog will make a film about them. That is, if they aren’t speaking to the camera itself.

From the beginning, Herzog’s nimbly drawling voice introduces Dengler indirectly: “Men are often haunted by things that happen to them in life, especially in times of war or other periods of great intensity. Sometimes you see these men walking the streets or driving in a car. Their lives seem to be normal, but they are not.” There isn’t much of a stretch from that comment to the heart of Herzog’s ecstatic truth. His manipulation of documentary narrative extracts that abnormality from the normal, that extraordinary-ness from the ordinary, from people who by their nature aren’t going to offer it up. The only way to witness such surreality—and such hidden depths of emotion—is to tease it out, using the camera to reveal it. Behind every magnificent contrivance in one of his films is an equally magnificent image, life revealed and thriving between the edges of the frame, ready to spill over.

Little Dieter Needs to Fly released almost four years before Dengler would die by suicide following a Parkinson’s diagnosis, his funeral filmed for a post-script attached to Little Dieter DVDs. In everything I’ve read about this film, mostly spoken or written by Herzog himself, suicide is never mentioned, though the information is easily available. I like to believe Herzog’s not preserving the illusion of optimism in his film by denying darker corners of Dengler’s personality, that he wouldn’t be so manipulative. He undoubtedly loves Dengler. But I don’t really know.

“I was careful about representing Dieter’s reality on screen, but did ask him to become an actor playing himself.” – Werner Herzog, Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed – Conversations with Paul Cronin

The Rehearsal, Nathan Fielder’s new HBO series, recently pulled from its shallow grave a century-old debate about the ethics of documentary filmmaking. What begins as a reality show where Fielder claims to help people solve life’s direst, most mundane challenges by coaching them through elaborately constructed simulations, effectively allowing them to practice any social situation, transforms under our noses into a weeks-long family “rehearsal” for the just-divorced Fielder to determine if he can train enough as a dad to actually, functionally be one.

One of the show’s most prominent critics was The New Yorker’s Richard Brody, who was rankled so fiercely by what he sees as Fielder’s unethical methods that he calls his review “The Cruel and Arrogant Gaze of Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal” and declares, “…barely five minutes into the first episode, I wanted to throw my laptop across the room or just to throw Nathan Fielder out of it.”

Brody’s anger assumes Fielder isn’t fulfilling his responsibility to the people he documents—namely to portraying their truth as accurately, or as according to their own wishes, as he can. Brody namechecks Jean Rouch and William Greaves as “Classics of docu-fiction” that “provide instructive comparisons” to Fielder’s solipsism. Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) is surely something of an Ur-text for Fielder’s approach, layering manufactured reality over manufactured reality until the film’s purpose returns to the feet of the director himself. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm weaves together three interdependent parts: 1) a documentary of the casting process for an in-progress film called Over a Cliff; 2) a documentary of the documentary of the casting process for an in-progress film called Over a Cliff, which include scene of Greaves’ crew openly criticizing his methods, scenes he records secretly; and 3) a documentary about the documentary of the documentary of the casting process for an in-progress film called Over a Cliff, wherein the director of the first documentary also happens to be directing the third documentary, which may or may not be what Over a Cliff is about. Because Fielder doesn’t show any of his crew resisting his increasingly invasive methods, they are, to Brody, “mere onscreen emblems of planning and labor” rather than real people with visible impact on the filmmaking process.

“Non-fiction film has always engaged with its own objectivity, relationship to those on camera, and constant striving for something that approaches ‘the truth,’” programmer/director Arlin Golden writes in a recent piece, “The Rehearsal Is Not a Documentary,” responding in part to Brody’s review. He continues, “The reputation of what’s popularly considered the first feature documentary, Nanook of the North, has been permanently weighed down by its now well-known inventions and flights of fancy.” Released in June of 1922, Robert J. Flaherty’s Nanook of the North represents just over 100 years of audiences attempting to un-speak the truth of documentary filmmaking into non-existence, ignoring the fiction at the core of the form.

Golden also speaks to Robert Greene and Sophy Romvari, two contemporary filmmakers whose documentaries ply at the edges of the medium. “I think Fielder is interested in what we fantasize about, how and why those dream lives manifest and what is happening within our brains as participants, filmmakers and viewers,” Greene says. “He’s interested in artifice and real lives and how meaning can be generated by placing the real and staged next to each other.”

In Guide for the Perplexed, Herzog admits he made up Dengler’s line about “chasing the demons away,” that the man wasn’t all that noticeably disturbed by the reenactment process. “The key thing is that every single decision we see the Nathan Fielder character make, Nathan Fielder the director wants us to question,” Greene says.

As Fielder mounts constructed realities around people who respond to a vague Craigslist post, building full recreations of bars and apartments and studios, he can’t resist eventually recreating relationships, lives and even recreations. The more The Rehearsal lays bare the manufactured state of the character Nathan Fielder’s life, the clearer the real Nathan Fielder becomes. Maybe there’s no sincerer take on Nathan Fielder than Nathan Fielder the actor, playing himself.

“There is flight in my imagination,” Herzog told Karen Beckman in 2007, “…there is something beyond our physicality, something that is not in our bodies.” He then recalled his very good friend from a long time ago, the subject of The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, a record-holding ski jumper, saying Steiner “became some sort of an embodiment of my own dreams. Somebody who physically does and steps outside of me and materializes in someone else whom I love very dearly. Because he flew. He flew instead of me.”

The real Dieter Dengler may be a far cry from the Dieter Dengler of Little Dieter Needs to Fly, but my heart tells me otherwise. For all its contrivance, all it resists or indulges, Little Dieter Needs to Fly is an act of love. In Rescue Dawn, Herzog’s 2006 dramatization of Little Dieter, Christian Bale goes method to portray Dengler at his closest to death, but there is nothing showy about what Bale puts his body through. The movie does not constantly draw attention to its own shocking turmoil, but instead lives in it, quietly supplicant to it. It’s a sober de-mythologizing of Dengler; he’s no less the impressive man in the documentary, but he sometimes seems realer in Bale’s version, a man whose trauma supersedes his brave accomplishment of surviving the worst. Whose psychological pain outweighs the spectacle of his story. In Dengler, Herzog sees his own dreams realized, and punished, and hopefully redeemed. He can’t make a film about Dengler without making it about himself too, so he doesn’t bother trying not to. Together they’ll share the responsibility of telling this story, of venturing into the past and reliving memories with their whole bodies, of playing themselves as characters who know, with intense sympathy for their unexplainable plight, Werner Herzog will make a film about them some day.

You can watch Little Dieter Needs to Fly right now on Tubi and on YouTube

Dom Sinacola is a Portland-based writer and editor. He’s also on Twitter.