The 50 Best Movies on YouTube (Free and Paid) Right Now

YouTube has as deep a selection of new movies as anyone, as long as you’re willing to pay to stream. But the video streaming service also has a great, if hard-to-find, selection of legal free movies. Really! And we’re not talking weirdly uploaded, grainy, sketchy films. Real deal, 100% free (and good) movies are out there alongside viral stars and adorable animal montages.

This treasure trove includes a wide range of classics that are free because they’ve entered the public domain, along with a selection of hidden gems among YouTube’s official selection of free movies (you have to really dig to find them among a lot of straight-to-DVD titles and knock-offs). We’ve divided these movies into two sections: the 25 best free movies on YouTube and 25 other, often newer movies on YouTube you’ll have to pay for—all updated every month.

You can also check out our guides to the best movies on Netflix, Amazon Prime, Max, Hulu, On Demand, at Redbox and in theaters. Or visit all our Paste Movie Guides.

First, here are the 25 Best Free Movies on YouTube:

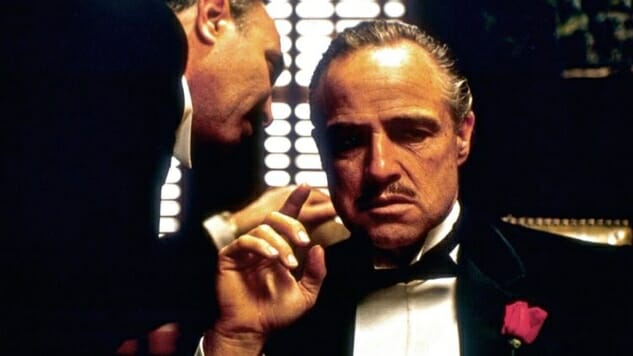

1. The Godfather

Year: 1972

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Stars: Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, Diane Keaton

Rating: R

The definitive immigrant story/definitive American tragedy: These are the awful things we are forced to do, and this is whom we do them for. The best mob stories ask: “How do I take care of me and mine?” How far are you willing to go to protect your own? In The Godfather and its sequels, the story of the Corleone family becomes the centerpiece of a deep meditation on family and power. Francis Ford Coppola answers: Ultimately, you will lose one in the vain pursuit of the other. During the second film, Family don Michael’s (Al Pacino) wife Kay (Diane Keaton, unrecognizable in her youth) gets her one really powerful scene as she reveals to her husband that she had an abortion because she can’t bear the thought of raising another child in the mob. He wouldn’t understand, she rants, because of “this Sicilian thing that’s been going on for 2,000 years!” Before, we flash back to 1941 and the fight that results from Michael revealing his enlistment in the Marines to his family: either the beginning of his personal fall or one last reminder that he’s always viewed himself as apart, as better. True tragedy comes from a fatal, internal flaw, and something about this scene is meant to suggest his. His family leaves him in the room alone. The only other times that both Michael and Vito (Marlon Brando; Robert De Niro) are alone on screen in the films occur in the tense moments before they kill—always in explicit defense of the family. Flash forward to Michael on a park bench by himself —years later, after he’s driven away his wife and his sister and seen countless people killed, many by his own order. The lonely horn section of the waltz motif plays us out. Long before that, Michael asks his mother if a man can lose his family in the struggle to protect it. It’s a question we’ve already answered.These are the awful things we are forced to do, and this is whom we do them for. At least, for Coppola, that’s what we tell ourselves. —Ken Lowe

2. Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Year: 1928

Director: Buster Keaton and Charles Reisner

Stars: Buster Keaton, Ernest Torrence, Marion Byron

Rating: NR

Steamboat Bill, Jr.’s climactic cyclone sequence—which is at once great action and great comedy—would on its own earn the film a revered place in the canon of great all time silent film. The iconic shot of a house’s facade falling on Keaton is only one of many great moments in the free-flowing, hard-blowing sequence. But Steamboat Bill, Jr. also showcases some of Keaton’s marvelous intimacy as an actor, such as a scene in which his father tries to find him a more manly hat, or during a painfully hilarious attempt to pantomime a jailbreak plan. —Jeremy Mathews

3. Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Year: 1975

Director: Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones

Stars: Graham Chapman, Eric Idle, Michael Palin, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Terry Jones

Rating: PG

It sucks that some of the shine has been taken off Holy Grail by its own overwhelming ubiquity. Nowadays, when we hear a “flesh wound,” a “ni!” or a “huge tracts of land,” our first thoughts are often of having full scenes repeated to us by clueless, obsessive nerds. Or, in my case, of repeating full scenes to people as a clueless, obsessive nerd. But, if you try and distance yourself from the over-saturation factor, and revisit the film after a few years, you’ll find new jokes that feel as fresh and hysterical as the ones we all know. Holy Grail is, indeed, the most densely packed comedy in the Python canon. There are so many jokes in this movie, and it’s surprising how easily we forget that, considering its reputation. If you’re truly and irreversibly burnt out from this movie, watch it again with commentary, and discover the second level of appreciation that comes from the inventiveness with which it was made. It certainly doesn’t look like a $400,000 movie, and it’s delightful to discover which of the gags (like the coconut halves) were born from a need for low-budget workarounds. The first-time co-direction from onscreen performer Terry Jones (who only sporadically directed after Python broke up) and lone American Terry Gilliam (who prolifically bent Python’s cinematic style into his own unique brand of nightmarish fantasy) moves with a surreal efficiency. —Graham Techler

4. Full Metal Jacket

Year: 1987

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Stars: Matthew Modine, Lee Ermey, Vincent D’Onofrio, Adam Baldwin

Rating: R

It’s a non-controversial opinion that Full Metal Jacket’s worth extends as far as its first half and declines from there as the film nosedives into conventionality. But the second chapter of Stanley Kubrick’s Vietnam horror story is responsible for creating the conventions by which we’re able to judge the picture in retrospect, and even conventional material as delivered by an artist like Kubrick is worth watching: Full Metal Jacket’s back half is, all told, pleasingly gripping and dark, a naked portrait of how war changes people in contrast to how the military culture depicted in the front half changes people. Being subject to debasement on a routine basis will break a person’s mind in twain. Being forced to kill another human will collapse their soul. Really, there’s nothing about Full Metal Jacket that doesn’t work or get Kubrick’s point across, but there’s also no denying just how indelible its pre-war sequence is, in particular due to R. Lee Ermey’s immortal performance as the world’s most terrifying Gunnery Sergeant. —Andy Crump

5. Interstellar

Year: 2014

Director: Christopher Nolan

Stars: Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, Bill Irwin, Ellen Burstyn, Matt Damon, Michael Caine

Rating: PG-13

Whether he’s making superhero movies or blockbuster puzzle boxes, Christopher Nolan doesn’t usually bandy with emotion. But Interstellar is a nearly three-hour ode to the interconnecting power of love. It’s also his personal attempt at doing in 2014 what Stanley Kubrick did in 1968 with 2001: A Space Odyssey, less of an ode or homage than a challenge to Kubrick’s highly polarizing contribution to cinematic canon. Interstellar wants to uplift us with its visceral strengths, weaving a myth about the great American spirit of invention gone dormant. It’s an ambitious paean to ambition itself. The film begins in a not-too-distant future, where drought, blight and dust storms have battered the world down into a regressively agrarian society. Textbooks cite the Apollo missions as hoaxes, and children are groomed to be farmers rather than engineers. This is a world where hope is dead, where spaceships sit on shelves collecting dust, and which former NASA pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) bristles against. He’s long resigned to his fate but still despondent over mankind’s failure to think beyond its galactic borders. But then Cooper falls in with a troop of underground NASA scientists, led by Professor Brand (Michael Caine), who plan on sending a small team through a wormhole to explore three potentially habitable planets and ostensibly secure the human race’s continued survival. But the film succeeds more as a visual tour of the cosmos than as an actual story. The rah-rah optimism of the film’s pro-NASA stance is stirring, and on some level that tribute to human endeavor keeps the entire yarn afloat. But no amount of scientific positivism can offset the weight of poetic repetition and platitudes about love. —Andy Crump

6. Hundreds of Beavers

Year: 2024

Director: Mike Cheslik

Stars: Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, Olivia Graves, Wes Tank

Rating: NR

Hundreds of Beavers is a lost continent of comedy, rediscovered after decades spent adrift. Rather than tweaking an exhausted trend, the feature debut of writer/director Mike Cheslik is an immaculately silly collision of timeless cinematic hilarity, unearthed and blended together into something entirely new. A multimedia extravaganza of frozen idiocy, Hundreds of Beavers is a slapstick tour de force—and its roster of ridiculous mascot-suited wildlife is only the tip of the iceberg. First things first: Yes, there are hundreds of beavers. Dozens of wolves. Various little rabbits, skunks, raccoons, frogs and fish. (And by “little,” I mean “six-foot stuntmen in cheap costumes.”) We have a grumpy shopkeeper, forever missing his spittoon. His impish daughter, a flirty furrier stuck behind his strict rage. And one impromptu trapper, Jean Kayak (co-writer/star Ryland Brickson Cole Tews), newly thawed and alone in the old-timey tundra. Sorry, Jean, but you’re more likely to get pelted than to get pelts. With its cartoonish violence and simple set-up comes an invigorating elegance that invites you deeper into its inspired absurdity. And Hundreds of Beavers has no lack of inspiration. The dialogue-free, black-and-white comedy is assembled from parts as disparate as The Legend of Zelda, Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, JibJabs, Terry Gilliam animation, Guy Maddin and Jackass. Acme is namechecked amid Méliès-like stop tricks and Muppety puppetry, while its aesthetic veers from painting broad violence upon a sparse snowy canvas to running through the shadowy bowels of an elaborate German Expressionist fortress. Guiding us through is Tews. He’s a wide-eyed mime with a caricatured lumberjack body, expertly gauging his expressions and sacrificing his flesh for the cause. His performance takes a little from the heavy-hitters of the form: The savvy romanticism of Harold Lloyd, the physical contortions of Buster Keaton, the underdog struggles of Charlie Chaplin, and the total bodily commitment of all three. You don’t get great physical comedy accidentally. Just as its intrepid idiot hero forges bravely on despite weathering frequent blows to the head, impaled extremities and woodland beatings, Hundreds of Beavers marches proudly towards the sublime transcendence of juvenilia. In its dedication to its own premise, Hundreds of Beavers reaches the kind of purity of purpose usually only found in middle-school stick-figure comics or ancient Flash animations—in stupid ideas taken seriously. One of the best comedies in the last few years, Hundreds of Beavers might actually contain more laughs than beavers. By recognizing and reclaiming the methods used during the early days of movies, Mike Cheslik’s outrageous escalation of the classic hunter-hunted dynamic becomes a miraculous DIY celebration of enduring, universal truths about how we make each other laugh.–Jacob Oller

7. Death Becomes Her

Year: 1992

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Stars: Meryl Streep, Goldie Hawn, Bruce Willis

Rating: PG-13

I adored Death Becomes Her when I first saw it as a child, but I only came to appreciate (what surely resonated for me then as) the film’s gay sensibility as an adult. I wanted to live like Isabella Rosselini, dripping in jewels (and nothing else), eternally beautiful and young, attended by a beefcake houseboy in her LA mansion. Fashion, location and taste may change, but the outlines of our desires are a constant, no? I still delight at the razor sharp barbs that fly between aging movie star Madeline (Meryl Streep) and her novelist friend Helen (Goldie Hawn), sterling examples of the acerbic queer humor in which the side-splitting takedown is also an act of love. It’s no surprise that the film has been much adored by the drag community, who find in Streep and Hawn rich possibilities for diva camp. Death Becomes Her also featured ambitious special effects that lent the movie a wonderful surrealism, only enhancing its comedy. I’d rather watch Hawn emerge out of that bloody Greystone fountain, the gaping hole in her stomach framing Streep and Willis like a family portrait, than Robert Patrick oozing into shape as the T-1000 in Terminator 2, which came out a year earlier and set a new standard. If you haven’t seen it, you should. But first, a warning—“NOW a warning?!”—you’ll be quoting it for weeks to come. —Eric Newman

8. Fear and Desire

Year: 1953

Director: Stanley Kubrick

A 24-year-old Stanley Kubrick’s feature debut, which he later described as “a bumbling amateur film exercise,” Fear and Desire proves the filmmaker a clear-eyed judge of his own work. That’s not to say there’s nothing to like in the hour-long war film, a meandering and tepid critique of the ahem “police action” in Korea, but that those things to like are immature interests engaged with by a filmmaker still learning the craft. The purple prose of future Pulitzer-winner Howard Sackler fills both dialogue and voiceover with strained metaphors and abstract intellectualizing, and the actors, by and large, respond to the overwritten material by overacting it. Frank Silvera, who would appear in Kubrick’s much better follow-up Killer’s Kiss, finds the most humanity in the quartet of soldiers crash-landed behind enemy lines by going grimier and gruffer than the rest. His no-frills blue collar approach—contrasted against the simpering mania of Paul Mazursky (the Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice filmmaker making his acting debut here) and near comic-strip sincerity of Kenneth Harp—encourage us to read some of the intentional ambiguity of the film’s emotions on his face. And Kubrick’s faces are still at the forefront: A mid-movie freakout between Mazursky’s private and a local woman he’s captured is both the film’s best scene and perhaps the director’s first example of that disconcerting straight-at-the-camera look that—thanks to A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Fear and Desire’s superior foil, Full Metal Jacket, and others—has become known as the Kubrick Stare. Representative of violence and desire and how those two always seem to be neighbors in men, the look is a brief but telling stylistic choice in a scene filled with pet themes and physicalizations of these ideas. Grasping hands and spilled stew create some of the most memorable images, but that the images are what remain most memorable from the movie is itself a kind of indicator. As a film, Fear and Desire doesn’t live up to its experimental ambitions; as a “film exercise,” it’s a showcase for a director who’s got an eye and is quickly developing everything else.—Jacob Oller

9. Waves

Year: 2019

Director: Trey Edward Shults

Stars: Kelvin Harrison Jr., Taylor Russell, Sterling K. Brown, Renée Elise Goldsberry, Alexa Demie, Lucas Hedges

Rating: R

“You gotta take pride in what you do, son,” Ronald (Sterling K. Brown) sternly tells Tyler (Kelvin Harrison Jr.). A man of high expectations, Ronald pushes his son to perform—and Tyler doesn’t handle those expectations in the best way. Written and directed by Trey Edward Shults, Waves explores grief, trauma and healing as a consequence of a young man snapping under pressure. On the surface, Tyler has the perfect life: a supportive family, a loving girlfriend, Alexis (Alexa Demie), and a wrestling career that’s on track to take him to college. Under the watchful eye of his father, he has a strict exercise regimen. But when he develops an injury, his anxiousness to perform for his father overwhelms him, his accident snowballing into a series of unfortunate events.

The prominent source of Waves’s beauty is its stellar cast. Kelvin Harrison Jr. has proven he has a knack for playing off-balance characters since Julius Onah’s Luce; as Tyler, he balances rebellion and anxiety with aplomb. It’s truly captivating to witness his fast descent into madness while posing as an immovable force to his loved ones. Sterling K. Brown, as the inflexible elder, sparks moments with Tyler that, while well-intentioned, are explosive, fostering a tete-a-tete between father and son that is equally uncomfortable and relatable. —Joi Childs

10. Sherlock Jr.

Year: 1924

Director: Buster Keaton

You could make a highlight reel of classic silent comedy moments using only Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr., and no one could justly complain. In the 91 years since Keaton made his love letter to cinema, no one has crafted a better examination of the relationship between the audience and the silver screen. Keaton plays a movie theater projectionist and wannabe detective who dreams he walks into a movie screen and becomes a suave hero—the perfect metaphor for the appeal of the movies. Keaton plays with reality through virtuoso special effects, but also captures genuine stunts in single takes. (He broke his neck in one scene and still finished the take.) He daringly subverts structure—the conflict is resolved halfway through the movie with no help from the hero. He brings visual poetry to slapstick with rhyming gags. The laughs coming from failure in the real world and serendipity in the fantasy movie world, but the mechanics parallel each other. And he strings it all into a romp that never stops moving toward more hilarity.—Jeremy Mathews

11. Nosferatu

Year: 1929

Director: F. W. Murnau

Stars: Max Schreck, Alexander Granach, Gustav von Wangenheim

F.W. Murnau’s sublimely peculiar riff on Dracula has been a fixture of the genre for so long that to justify its place on this list seems like a waste of time. Magnificent in its freakish, dour mood and visual eccentricities, the movie invented much of modern vampire lore as we know it. It’s once-a-year required viewing of the most rewarding kind. —Sean Gandert

12. Black Christmas

Year: 1974

Director: Bob Clark

Stars: Olivia Hussey, Margot Kidder, Keir Dullea, Andrea Martin, John Saxon

Rating: R

Fun fact—nine years before he directed holiday classic A Christmas Story, Bob Clark created the first true, unassailable “slasher movie” in Black Christmas. Yes, the same person who gave TBS its annual Christmas Eve marathon fodder was also responsible for the first major cinematic application of the phrase “The calls are coming from inside the house!” Black Christmas, which was insipidly remade in 2006, predates John Carpenter’s Halloween by four years and features many of the same elements, especially visually. Like Halloween, it lingers heavily on POV shots from the killer’s eyes as he prowls through a dimly lit sorority house and spies on his future victims. As the mentally deranged killer calls the house and engages in obscene phone calls with the female residents, one can’t help but also be reminded of the scene in Carpenter’s film where Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) calls her friend Lynda, only to hear her strangled with the telephone cord. Black Christmas is also instrumental, and practically archetypal, in solidifying the slasher legend of the so-called “final girl.” Jessica Bradford (Olivia Hussey) is actually among the better-realized of these final girls in the history of the genre, a remarkably strong and resourceful young woman who can take care of herself in both her relationships and deadly scenarios. It’s questionable how many subsequent slashers have been able to create protagonists who are such a believable combination of capable and realistic. —Jim Vorel

13. A Fistful of Dollars

Year: 1964

Director: Sergio Leone

Stars: Clint Eastwood, Marianne Koch, Josef Egger, Wolfgang Lukschy, Gian Maria Volonté, Daniel Martín, Bruno Carotenuto, Benito Stefanelli

Rating: R

What’s the saying? If you’re going to steal, steal from the best. That’s what Sergio Leone did back in 1964, when he released A Fistful of Dollars upon the world and in doing so reinvigorated a whole genre under the “Spaghetti Western” tag. The film is a straight-up rip-off of Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece, Yojimbo, and unapologetically so. But Leone proves that lifting a story out of its setting and populating it with a whole new cast of characters works as a narrative tactic. He made stronger movies throughout his career, but A Fistful of Dollars, for all of its influence over the Western from the 1960s forward, is arguably his most important. —Andy Crump

14. Bernie

Year: 2011

Director: Richard Linklater

Stars: Jack Black, Matthew McConaughey, Shirley MacLaine

Bernie is as much about the town of Carthage, Texas, as it is about its infamous resident Bernie Tiede (Jack Black), the town’s mortician and prime suspect in the murder of one of its most despised citizens, Marjorie Nugent (Shirley MacLaine). Unlike Nugent, Bernie is conspicuously loved by all. When he’s not helping direct the high school musical, he’s teaching Sunday school. Like a well-played mystery, Linklater’s excellent, darkly humorous (and true) story is interspersed with tantalizing interviews of the community’s residents. Linklater uses real East Texas folks to play the parts, a device that serves as the perfect balance against the drama that leads up to Bernie’s fatal encounter with the rich bitch of a widow. The comedy is sharp, with some of the film’s best lines coming from those townsfolk. —Tim Basham

15. Blackmail

Year: 1929

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Stars: Anny Ondra, John Longden, Donald Calthrop

Alfred Hitchcock’s first sound film was also his last silent, as Blackmail was made in both formats. While the sound version is known for Hitchcock’s experiments with the new technology (most famously a scene that emphasizes the word “knife”), the silent version flows much smoother. And Donald Calthrop’s performance of the blackmailer feels even creepier with just his face and body language doing the job. —Jeremy Mathews

16. Pumping Iron

Year: 1977

Director: Robert Fiore, George Butler

Rating: PG

Behold arrogance anthropomorphized: A 28-year-old Arnold Schwarzenegger, competing for his sixth Mr. Olympia title, effortlessly waxes poetic about his overall excellence, his litanies regarding the similarities between orgasming and lifting weights merely fodder between bouts of pumping the titular iron and/or flirting with women he can roll up into his biceps like little flesh burritos. He is both the epitome of the human form and almost tragically inhuman, so corporeally perfect that his physique seems unattainable, his status as a weightlifting wunderkind one of a kind. And yet, in the other corner, a young, nervous Lou Ferrigno primes his equally large body to usurp Arnold’s title, but without the magnanimous bluster and dick-wagging swagger the soon-to-be Hollywood icon makes no attempt to hide. Schwarzenegger understands that weightlifting is a mind game (like in any sport), buttressed best by a healthy sense of vanity and privilege, and directors Fiore and Butler mine Arnold’s past enough to divine where he inherited such self-absorption. Contrast this attitude against Ferrigno’s almost morbid shyness, and Pumping Iron becomes a fascinating glimpse at the kind of sociopathy required of living gods. —Dom Sinacola

17. The Kid

Year: 1921

Director: Charlie Chaplin

Stars: Charlie Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Edna Purviance

Charlie Chaplin’s first full-length film and one of his finest achievements, The Kid tells the story of an abandoned child and the life he builds with The Little Tramp. Chaplin went against heavy studio opposition to create a more serious film in contrast to his earlier work. However, The Kid features just as much slapstick humor as his previous shorts, but placed within a broader, more dramatic context. —Wyndham Wyeth

18. Night of the Living Dead

Year: 1968

Director: George A. Romero

Stars: Judith O’Dea, Russell Streiner, Duane Jones

Rating: R

It’s not really necessary to delve into how influential George Romero’s first zombie film has been to the genre and horror itself—it’s one of the most important horror movies ever made, and one of the most important independent films as well. The question is more accurately, “how does it hold up today?”, and the answer is “okay.” Unlike, say Dawn of the Dead (not on Shudder), Night is pretty placid most of the time. The story conventions are classic and the black-and-white cinematography still looks excellent, but some of the performances are downright irritating, particularly that of Judith O’Dea as Barbara. Duane Jones more than makes up for that as the heroic Ben, however, in a story that is very self-sufficient and provincial—just one small group of people in a house, with no real thought to the wider world. It’s a horror film that is a MUST SEE for every student of the genre, which is easy, considering that the film actually remains in the public domain. But in terms of entertainment value, Romero would perfect the genre in his next few efforts. Also recommended: The 1990 remake of this film by Tom Savini, which is unfairly derided just for being faithful to its source. —Jim Vorel

19. Ghost in the Shell

Year: 1995

Director: Mamoru Oshii

It’s difficult to overstate how enormous of an influence Ghost in the Shell exerts over not only the cultural and aesthetic evolution of Japanese animation, but over the shape of science-fiction cinema as a whole in the 21st century. Adapted from Masamune Shirow’s original 1989 manga, the film is set in the mid-21st century, a world populated by cyborgs in artificial prosthetic bodies, in the fictional Japanese metropolis of Niihama. Ghost in the Shell follows the story of Major Motoko Kusanagi, the commander of a domestic special ops task-force known as Public Security Section 9, who begins to question the nature of her own humanity surrounded by a world of artificiality. When Motoko and her team are assigned to apprehend the mysterious Puppet Master, an elusive hacker thought to be one of the most dangerous criminals on the planet, they are set chasing after a series of crimes perpetrated by the Puppet Master’s unwitting pawns before the seemingly unrelated events coalesce into a pattern that circles back to one person: the Major herself. Everything about Ghost in the Shell shouts polish and depth, from the ramshackle markets and claustrophobic corridors inspired by the likeness of Kowloon Walled City, to the sound design, evident from Kenji Kawai’s sorrowful score, to the sheer concussive punch of every bullet firing across the screen. Oshii took Shirow’s source material and arguably surpassed it, transforming an already heady science-fiction action drama into a proto-Kurzweil-ian fable about the dawn of machine intelligence. Ghost in the Shell is more than a cornerstone of cyberpunk fiction, it’s a story about what it means to craft one’s self in the digital age, a time where the concept of truth feels as mercurial as the net is vast and infinite. —Toussaint Egan

20. The Last Man on Earth

Year: 1964

Directors: Ubaldo Ragona, Sidney Salkow

Stars: Vincent Price, Tony Cerevi, Franca Bettoja

Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend has proven notoriously difficult to adapt while keeping any of its ideas intact, but compared to the later Omega Man or 2007 version of I Am Legend with Will Smith, this is probably the best overall take on the story. Some have called it Vincent Price’s best film, featuring wonderfully gothic settings in Rome where the last human man on Earth wages a nightly war against the “infected,” who have taken on the characteristics of classical vampires. It doesn’t fully commit to the inversion of protagonist/antagonist of the source material, but it makes the use of Price’s magnetic screen presence and ability to monologue. No one ever watches a Vincent Price movie and thinks “I wish there was less Vincent Price in this,” and The Last Man on Earth delivers a showcase for the actor at the height of his powers. Night of the Living Dead director George Romero has stated that without The Last Man on Earth, the modern zombie would never have been conceived. —Jim Vorel

21. The Red Turtle

Year: 2016

Director: Michaël Dudok de Wit

Stars: Emmanuel Garijo, Tom Hudson

Rating: PG

Wordless, The Red Turtle is an attempt to find new ways to communicate old truths—or old new ways, ways that feel new but aren’t. There is one word in The Red Turtle, but its isolation amongst the loud non-language of the rest of the film—the ever-present, somnambulant waves; the fauna of the film’s tiny “deserted” island; Laurent Perez del Mar’s score, which itself feels tuned to the natural rhythm of the world emerging within Michaël Dudok de Wit’s animated film—makes us question if it is actually a word at all. “Hey!” our nameless main character yells, otherwise carrying on a lifetime of subverbal communication, but it’s uttered so often amidst de Witt’s carefully built soundscape that it’s not all that impossible for the director to convince you there are no words in his film. Perhaps, a man of both Dutch and British descent, de Wit finds language a barrier between the audience and the emotional breadth of his (admittedly pretty archetypal) story, further inspired to ditch dialogue altogether by the film’s joint Japanese-French funding, and by the fact that if there’s any feature-length cinematic medium more forgiving of having no words, it’s animation. Consider that one simple example among many of the film’s power: Just as The Red Turtle could make you doubt whether a word you’ve known your whole life is actually that, so does it leave you with plenty of wonder—whether all animated films could be so lovely, so careful, so obviously the work of one person who’s given his everything to a single story because he might not have an opportunity to do so ever again. —D.S.

22. The Lady Vanishes

Year: 1938

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Stars: Margaret Lockwood, Michael Redgrave, Paul Lukas

Rating: PG

Pretty much predating every trope you’ve ever come to expect out of a genre that gets its name from keeping the audience keyed-up, The Lady Vanishes is both hilariously dated and a by-the-numbers primer on how to make a near-perfect thriller. Far from Hitchcock’s first foray into suspense, the film follows a soon-to-be-married woman, Iris (Margaret Lockwood), who becomes tangled in the mysterious circumstances surrounding the titular lady’s disappearance aboard a packed train. No shot in the film is extraneous, no piece of dialogue pointless—even the ancillary characters, who serve little ostensible part besides lending complexity to Iris’s search for the truth, are crucial to building the tension necessary to making said lady’s vanishing believable. The film is a testament to how, even by 1938, Hitchcock was shaving each of his films down to their most empirical parts, ready to create some of the most vital genre pictures of the 1950s. —Dom Sinacola

23. Donnie Darko

Year: 2001

Director: Richard Kelly

Stars: Jake Gyllenhaal, Jena Malone, Mary McDonnell, Holmes Osborne, Patrick Swayze, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Daveigh Chase, James Duval, Arthur Taxier

Rating: R

Apparently, at some point in its burgeoning cult ascendency, director Richard Kelly admitted that even he didn’t totally get what’s going on in Donnie Darko—going so far as to release a “Director’s Cut” in 2005 that supposedly cleared up some of the film’s more unwieldy stuff. Yet another example of a small budget wringed of its every dime, Kelly’s debut crams love, weird science, jet engines, superhero mythology, wormholes, armchair philosophy, giant bunny rabbits and Patrick Swayze (as a child molester, no less) into a film that should be celebrated for its audacity more than its coherency. It also helps that Jake Gyllenhaal leads a stellar cast, all totally game. In Donnie Darko, the only thing that’s clear is Kelly’s attitude: that at its core cinema is the art of manifesting the unbelievable, of doing what one wants to do when one wants to do it. —Christian Becker

24. Paprika

Year: 2006

Director: Satoshi Kon

Stars: Megumi Hayashibara, Toru Furuya, Koichi Yamadera

Rating: R

In a career of impeccable films, Paprika is arguably Kon’s greatest achievement. Adapted from the 1993 novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui (whose other notable novel, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, would form the basis of Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 film of the same name), Kon could not have asked for source material that better suited his thematic idiosyncrasies as a director. Paprika follows the story of Atsuko Chiba, a psychiatrist working on revolutionary psychotherapy treatment involving the DC Mini, a device that allows the user to record and navigate one’s dreams in a shared simulation. By day Atsuko maintains an unremittingly cold exterior, but by night she moonlights as the film’s titular protagonist: a vivacious dream detective who consults clients on her own terms. When a pair of DC Minis are stolen and loosed upon the world, causing a stream of havoc which manifests the collective unconscious into the waking world, it’s up to Paprika and her colleagues to save the day. The summation of Kon’s decade-long career as a director, Paprika is a cinematic trompe l’oeil of psychedelic colors and exquisite animation. Kon’s transition cuts are memorable and mind bending, the allusions to his immense palate of cinematic influences are savvy, and his appeal to the multiplicity of the human experience as thoughtful and poignant as ever. Unfortunately, Paprika would turn out to be Kon’s last film, as he would later tragically pass away in 2010 from pancreatic cancer. One fact remains evident when looking back on the sum total of his life’s work: Satoshi Kon was, and remains, one of the greatest anime directors of his time. He will be sorely missed.–Toussaint Egan

25. Heathers

Year: 1989

Director: Michael Lehmann

Stars: Winona Ryder, Christian Slater, Kim Walker

Rating: R

As much an homage to ’80s teen romps—care of stalwarts like John Hughes and Cameron Crowe—as it is an attempt to push that genre to its near tasteless extremes, Heathers is a hilarious glimpse into the festering core of the teenage id, all sunglasses and cigarettes and jail bait and misunderstood kitsch. Like any coming-of-age teen soap opera, much of the film’s appeal is in its vaunting of style over substance—coining whole ways of speaking, dressing and posturing for an impressionable generation brought up on Hollywood tropes—but Heathers embraces its style as an essential keystone to filmmaking, recognizing that even the most bloated melodrama can be sold through a well-manicured image. And some of Heathers’ images are indelible: J.D. (Christian Slater) whipping out a gun on some school bullies in the lunch room, or Veronica (Winona Ryder) passively lighting her cigarette with the flames licking from the explosion of her former boyfriend. It makes sense that writer Daniel Waters originally wanted Stanley Kubrick to direct his script: Heathers is a filmmaker’s (teen) film. —Dom Sinacola

And here are 25 newer movies you can buy or rent on YouTube:

Prices range from 99 cents to $8.99.

26. Undine

Year: 2021

Director: Christian Petzold

Stars: Paula Beer, Franz Rogowski, Maryam Zeree, Jacob Matschanz, Anne Ratte-Polle

Rating: NR

Undine opens as a rom-com might. A lilting piano score, not without a shade of sadness, purrs quietly during the title cards. A tearful break-up presages a quirky meet-cute between industrial diver Christoph (Franz Rogowski) and city historian Undine (Paula Beer), our new couple bound by the irrevocable forces of chance—and, in director Christian Petzold’s own mannered way, a bit of physical comedy—as the universe clearly arranges for the pieces of their lives to come together. Squint and you could maybe mistake these opening moments for a Lifetime movie—that is, until the break-up ends with Undine warning her soon-to-be-ex (Jacob Matschenz) that she’s going to have to kill him. He doesn’t take Undine seriously, but the audience can’t be so sure. Beer’s face contains subtle multitudes. She could actually murder this guy. What once felt familiar now feels pregnant with dread. And that’s saying nothing about Christoph’s odds for survival. Anyone remotely familiar with the “Undine” tale knows that she’s not lying to her ex. Undine is a water spirit, making covenants with men on land in order to access a human soul (as well as a tasteful professional wardrobe). Breaking that covenant is fatal. Or so the story goes. When she meets Christoph, she’s revitalized, because she’s heartbroken but especially because he takes such interest in the subjects of her lectures. He too is bound to the evolving bones of Germany, repairing bridges and various underwater infrastructure—he may, in fact, be more intuitively connected to the country than most. He’s the rare person who’s gone beneath it, excavating and reconstructing its depths, entombed in the mech-like coffin of a diving suit he wears when welding below the surface. As in all of Petzold’s films, Undine builds a world of liminal spaces—of lives in transition, always moving—of his characters shifting between realities, never quite sure where one ends and another begins. Like genre, like architecture, like history, like a love affair—at the heart of his work is the push and pull between where we are and where we want to be, between who we are and who we want to be and what we’ve done and what we’ll do, between what we dream and what we make happen. In Undine, Petzold captures this tension with warmth and immediacy. Many, many lives have brought us here, but none are more important than these two, and no time more consequential than now. My god, how romantic.—Dom Sinacola

27. In Bruges

Year: 2008

Director: Martin McDonagh

Stars: Colin Ferrell, Brendan Gleeson, Ralph Fiennes

Rating: R

You know you’ve tripped into the ambiguous realm of Postmodernism when medieval Europe, midget jokes and ultraviolence converge into a seamless whole. Theater auteur Martin McDonagh’s debut feature, In Bruges, thrives on these stylistic clashes with its narrative of two sympathetic hitmen who seek refuge in a European wonderland full of tourists and irony. The film’s visual appeal complements irreverent and hilarious dialogue—timed brilliantly with the Anglo-Saxon bravado of Fiennes, Farrell and Gleeson—to produce one of a most pleasant dark-horse dramedy.—Sean Edgar

28. Licorice Pizza

Year: 2021

Director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Stars: Alana Haim, Cooper Hoffman, Sean Penn, Tom Waits, Bradley Cooper, Benny Safdie

Rating: R

Licorice Pizza is writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson’s second ode to Los Angeles in the early 1970s: A city freshly under the oppressive shadow of the Manson Family murders and the tail end of the Vietnam War. But while in his first tribute, Inherent Vice, the inquisitive counter-culture affiliate Doc Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) earnestly engages with his surroundings and follows the threads of societal paranoia all the way to vampiric drug smuggling operations and FBI conspiracies, Licorice Pizza’s protagonist, 25-year-old Alana Kane (Alana Haim), refuses to follow any such thread. A bored, directionless photographer’s assistant, Alana nonchalantly rejects any easy plot-point that might help us get a grasp on her character. What are her ambitions? She doesn’t know, she tells successful 15-year-old actor Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman, son of Philip Seymour Hoffman) over dinner at a restaurant called Tail o’ the Cock. What interests and excites her? It’s hard to say. When Gary first approaches Alana while she’s working picture-day at his high school, it’s hard to imagine that Licorice Pizza isn’t going to follow the playful design of a sunny Southern California love story. Alana is instantly strange and striking, and—when Anderson introduces her in a languid dolly-shot with a mini-skirt, kitten-heels, slumped shoulders and a gloriously pissed expression—we are compelled to fall in love with her, just like Gary does, at first sight. Of course, Anderson quickly rejects the notion that Licorice Pizza is going to be a straightforward romance. Anderson knows that this ambling, disjointed structure reflects what it’s like to be young, awkward and in love. Each shot, filled with dreamy pastels, glows with a youthful nostalgia. Anderson and cinematographer Michael Bauman balance out this haziness with a unique control of the camera, implementing long takes, slow dollies, and contemplative pans galore. What is it that Alana gets from being friends with someone ten years younger than her? And why does Gary always return to Alana even when she tries her best to put him down? Like gleefully gliding through the streets of L.A. in the midst of a city-wide crisis, it’s a madness you can only truly understand when you’re living it.—Aurora Amidon

29. The Sparks Brothers

Year: 2021

Director: Edgar Wright

Rating: R

The Sparks Brothers is a thorough and charming assessment and appreciation of an idiosyncratic band, and the highest praise you could give it is that it shares a sensibility with its inimitable musicians. Not an easy task when it comes to Ron and Russell Mael. The Californian brothers have been running Sparks since the late ‘60s (yeah, the ‘60s), blistering through genres as quickly as their lyrics make and discard jokes. Glam rock, disco, electronic pioneering—and even when they dip into the most experimental and orchestral corners of their musical interests, they maintain a steady power-pop genius bolstered by Russell’s fluty pipes and Ron’s catchy keys. It’s here, in Sparks’ incredible range yet solidified personality, that you quickly start to understand that The Sparks Brothers is the marriage of two perfect subjects that share a mission. Experts in one art form that are interested in each others’, Ron and Russell bond with director Edgar Wright over a wry desire to have their fun-poking and make it art too. One made a trilogy of parodies that stands atop its individual genres (zombie, cop, sci-fi movies). The others made subversive songs like “Music That You Can Dance To” that manage to match (and often overtake) the very bops they razz. Their powers combined, The Sparks Brothers becomes a music doc that’s self-aware and deeply earnest. Slapstick, with a wide range of old film clips delivering the punches and pratfalls, and visual gags take the piss out of its impressive talking heads whenever they drop a groaner music doc cliché. “Pushing the envelope?” Expect to see a postal tug-of-war between the Maels. This sense of humor, appreciating the dumbest low-hanging fruit and the highest brow reference, comes from the brothers’ admiration of seriously unserious French filmmakers like Jacques Tati (with whom Sparks almost made a film; remember, they love movies) and of a particularly formative affinity for British music. It doesn’t entirely tear down facades, as even Wright’s most personal works still emote through a protective shell of physical comedy and references, but you get a sense of the Maels as workers, brothers, artists and humans on terms that they’re comfortable with. The nearly two-and-a-half-hour film is an epic, there’s no denying that. You won’t need another Sparks film after this one. Yet it’s less an end-all-be-all biography than an invitation, beckoning newcomers and longtime listeners alike through its complete understanding of and adoration for its subjects.—Jacob Oller

30. The Novice

Year: 2021

Director: Lauren Hadaway

Stars: Isabelle Fuhrman, Amy Forsyth

Rating: R

Lauren Hadaway’s The Novice didn’t just surprise me, it ran wild over the rest of the movies I saw at the Chicago Critics Film Festival, trampling over my memories of them until it was certain that all I could think about was Hadaway’s full-throttle style and her film’s blistering performances. Only fitting for a movie about the consequences of toxic overachievement—of what happens when quasi-liberal education is a money-making machine, burning kids like coal. A movie that puts the “extra” in “extracurricular.” The Novice’s anxious and obsessive hustle culture horror wants to be #1 or nothing. No participation ribbons. And none will be necessary: Hadaway’s work signals a leap straight to the top of the podium as one of the year’s best debuts. Writer/director/editor Hadaway has worked most extensively up until now as an ADR and dialogue supervisor and sound editor for movies like Whiplash, and the precision with which she deploys brutal mental and physical obstacles in The Novice—manifested as everything from sound effects to harsh cuts to scribbled credits font—reflects her expertise. And that’s not even mentioning the heart of the film: A ferocious Isabelle Fuhrman as Alex Dall. Dall is a hardcore college freshman, intense in every facet of her life as she rechecks and overthinks physics tests, hooks up with a frat boy simply to get that experience out of the way, and decides to become a varsity rower…despite lacking any experience, y’know, rowing. You’ve probably heard that some filmmakers make cities into “characters.” Hadaway makes the open water into one of life’s only soothing, nearly sexual comforts; the brutalist concrete basement cell housing the team’s rowing machines into its seductive, enabling villain. The latter offers success, records—quantitative proof that Dall isn’t just good, but better than—while also being a sacrificial altar. The Novice’s unrelenting and self-assured neurosis requires some pitch-black punchlines, keyed-in dialogue and aesthetic chutzpah—which Hadaway displays in spades. Keep an eye on her, as The Novice may have just revealed an up-and-coming master.—Jacob Oller

31. Titane

Year: 2021

Director: Julia Ducournau

Stars: Agathe Rousselle, Vincent Lindon, Garance Marillier, Laïs Salameh

Rating: R

Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) had an early connection with cars. Her insistence on using her voice to mimic the rev of an engine as a young girl (played by Adèle Guigue) while her irritated father (French director Bertrand Bonello) drove was so undaunted that one day she caused him to lose control of the vehicle. The accident rendered her father mostly unscathed, and Alexia with a titanium plate implanted in her skull. It was a procedure that seemingly strengthened a curious linkage between her and metal and machine, an innate affection for something hot and alive that could never turn away Alexia’s love. As the doctor removes Alexia’s surgical metal headgear, her father looks on with something that can only be described as disdain for his child. Perhaps, it is because he knew what Alexia would become; perhaps, Alexia was just born bad. Julia Ducournau’s Palme d’Or-winning follow-up to 2016’s Raw crunches, tears and sizzles. Bones break, skin rips, libidos throb—the human body is pushed to impossible limits. It’s something that Ducournau has already proved familiarity with, but the French director takes things to new extremes with her sophomore film. Titane is a convoluted, gender-bending odyssey splattered with gore and motor oil, the heart of which rests on a simple (if exceedingly perverted) story of finding unconditional acceptance. Eighteen years following the childhood incident, Alexia is a dancer and car model, venerated by ravenous male fans aching to get a picture and an autograph with the punky, sharp-featured young woman. She splays her near-naked form atop the hood of an automobile to the beat of music, contorting and touching herself with simmering lust for the inanimate machine adorned with a fiery paint job to match Alexia’s sexuality. Pink and green and neon yellow glistens on every body (chrome or otherwise) in the showroom, but Ruben Impens’ cinematography follows Alexia as she guides us through this space where she feels most at home. Titane persists as a boundary-pushing exploration of the human form, of gender performance, masculinity and isolation; Ducournau’s script is surprising, shocking, titillating at every turn. And despite her cruelty, and the relative distance from and lack of insight into her character, Alexia remains an empathetic protagonist. This is in no small part thanks to Rousselle’s commanding portrayal which astonishingly doubles as her feature debut. Titane is not just 108 bloody minutes of bodily mutilation and perversion, but of blazing chaos inherent in our human need for acceptance. Ducournau has wrapped up this simple conceit in a narrative that only serves to establish her voice as one which demands our attention, even as we feel compelled to look away. Yes, it’s true what they’ve said—love will literally tear us apart.—Brianna Zigler

32. Martin Eden

Year: 2020

Director: Pietro Marcello

Stars: Luca Marinelli, Jessica Cressy, Denise Sardisco

Rating: PG

Martin Eden, Jack London’s 1909 novel, finally got an adaptation worthy of its author from Italian filmmaker Pietro Marcello. The wide-ranging, painterly and dense evolution of a sailor-turned-author (here played in alluring, heart-wrenching, ultra-charismatic form by Luca Marinelli) from his blue collar roots to the upper echelons of the in-vogue is a stunning drama with a lot on its mind. Eden’s infatuation with learning is linked to his equal infatuation with the upper-class Elena (Jessica Cressy), and the combination of the two stop his primal ways (signified by one-night stands and humorously nonchalant fistfights) in their tracks. Marinelli’s earthy confidence and swaggering sex appeal are ogled by everyone—he’s a burly, good-natured sailor after all—but it’s his ideas that shout out London’s railing commentary on class inequality. As the film’s complex politics (made more resonant through the setting change to Italy) debate messily imperfect socialism and the mercenary bootstrapping tactics of individualism, Eden embodies this ideological journey through an impressive physical transformation, turning waxen, weak and washed-up as his literary ambitions find the exact wrong kind of success. Marcello’s Martin Eden is akin to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon in its majestic beauty and society-spanning saga of a story, but with a meaner humor and rawer sense of criticism. The ex-documentarian’s penchant for slipping back and forth between old home movie-esque footage and his high art compositions make the dueling philosophies of the film even clearer. Somehow most impressive of all is Martin Eden’s success at making an exciting, engrossing film about a writer in which the writing process is actually fun (and beautiful) to watch. Marcello and co-writer Maurizio Braucci work London’s words into wonders.—Jacob Oller

33. The Paper Tigers

Year: 2021

Director: Bao Tran

Stars: Alain Uy, Ron Yuan, Mykel Shannon Jenkins, Roger Yuan, Matthew Page, Jae Suh Park, Joziah Lagonoy

Rating: PG-13

When you’re a martial artist and your master dies under mysterious circumstances, you avenge their death. It’s what you do. It doesn’t matter if you’re a young man or if you’re firmly living that middle-aged life. Your teacher’s suspicious passing can’t go unanswered. So you grab your fellow disciples, put on your knee brace, pack a jar of IcyHot and a few Ibuprofen, and you put your nose to the ground looking for clues and for the culprit, even as your soft, sapped muscles cry out for a breather. That’s The Paper Tigers in short, a martial arts film from Bao Tran about the distance put between three men and their past glories by the rigors of their 40s. It’s about good old fashioned ass-whooping too, because a martial arts movie without ass-whoopings isn’t much of a movie at all. But Tran balances the meat of the genre (fight scenes) with potatoes (drama) plus a healthy dollop of spice (comedy), to similar effect as Stephen Chow in his own kung fu pastiches, a la Kung Fu Hustle and Shaolin Soccer, the latter being The Paper Tigers’ spiritual kin. Tran’s use of close-up cuts in his fight scenes helps give every punch and kick real impact. Amazing how showing the actor’s reactions to taking a fist to the face suddenly gives the action feeling and gravity, which in turn give the movie meaning to buttress its crowd-pleasing qualities. We need more movies like The Paper Tigers, movies that understand the joy of a well-orchestrated fight (and for that matter how to orchestrate a fight well), that celebrate the “art” in “martial arts” and that know how to make a bum knee into a killer running gag. The realness Tran weaves into his story is welcome, but the smart filmmaking is what makes The Paper Tigers a delight from start to finish.—Andy Crump

34. Bill & Ted Face the Music

Year: 2020

Director: Dean Parisot

Stars: Keanu Reeves, Alex Winter, Kristen Schaal, Samara Weaving, Brigette Lundy-Paine, William Sadler

Rating: PG-13

Our enjoyment of Bill & Ted Face the Music may only be the direct result of living with a kind of background-grade dread for what feels like the whole of our adult lives. Those of us who will seek out and watch this third movie in the Most Excellent Adventures of Bill S. Preston, Esq. (Alex Winter) and Ted (Theodore) Logan (Keanu Reeves) are bound by nostalgia as much as a desire to suss out whatever scraps of joy can be found buried in our grim, harrowing reality. Sometimes, death and pain is unavoidable. Sometimes it just feels nice to lounge for 90 minutes in a universe where when you die you and all your loved ones just go to Hell and all the demons there are basically polite service industry workers so everything is pretty much OK. Cold comfort and mild praise, maybe, but the strength of Dean Parisot’s go at the Bill & Ted saga is its laid-back, low-stakes nature, wherein even the murder robot (Anthony Carrigan, the film’s luminous guiding light) sent to lazer Bill and Ted to death quickly becomes their friend while Kid Cudi is the duo’s primary source on quantum physics. Because why? It doesn’t matter. Nothing matters. There may be some symbolic heft to Bill and Ted reconciling with Death (William Sadler) in Hell; there may be infinite universes beyond our own, entangled infinitely. Cudi’s game for whatever. A sequel of rare sincerity, Bill & Ted Face the Music avoids feeling like a craven reviving of a hollowed-out IP or a cynical reboot, mostly because its ambition is the stuff of affection—for what the filmmakers are doing, made with sympathy for their audience and a genuine desire to explore these characters in a new context. Maybe that’s the despair talking. Or maybe it’s just the relief of for once confronting the past and finding that it’s aged considerably well. —Dom Sinacola

35. All Light, Everywhere

Year: 2021

Director: Theo Anthony

Rating: NR

The camera is a gun according to Theo Anthony, director of All Light, Everywhere, a patchwork documentary which blends interviews, archival footage and even scenes from the film’s cutting room floor in order to dissect the omnipresence of video surveillance—particularly in Black communities which have long been over-policed. Anthony’s filmic medium appears paradoxical considering his vested interest in critiquing the omission of unbiased truth inherent in camera footage—particularly those recorded by police body cams, covert aerial surveillance programs and panopticonic corporate workplaces. But as the director peels back the layers of his methodology, the viewer observes unpolished glimpses of Anthony setting up shots, prepping subjects for interview and divulging research logs—a technique that shatters the illusion of objectivity altogether. Through obliterating the guise of impartial filmmaking, Anthony examines the insidious history of image capturing as a tool of incarceration and its continued weaponization by the state. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy: Heightened surveillance in minority communities proliferates a high rate of crime—with infinite eyes scanning for crime, more crimes (predominantly minor offenses) are reported and prosecuted. Without the amplification of these invasive practices in affluent white communities, the false narrative of crime-riddled cities—like Anthony’s hometown of Baltimore—is infinitely reinforced. Perhaps the most insidious use of surveillance technology evident in All Light, Everywhere is the intentionally grainy, indeterminate nature of body camera footage itself, the argument being that if the cameras are too perceptive, too unbiased in their ability to document altercations between police and citizens, they might sway courtrooms to see the police’s actions as irresponsible or negligent. After all, if the jury can clearly see that a victim of police brutality was indeed holding a water gun instead of a deadly weapon, how could cops be expected to take accountability for their mistakes? If the premise of authoritarian monitoring isn’t terrifying enough, a scene involving AI-generated faces—composites of would-be individuals (or criminals)—pushes All Light, Everywhere into overt horror. Not just through the uncanny, skin-crawling quality of human non-humans, but by effectively presenting the evil inherent in these technologies when utilized against citizens by corrupt institutions.—Natalia Keogan

36. She Dies Tomorrow

Year: 2020

Director: Amy Seimetz

Stars: Kate Lyn Sheil, Jane Adams, Kentucker Audley

Rating: R

Amy (Kate Lyn Sheil), for inexplicable reasons, is infernally convinced that tomorrow’s the day she’s going to meet her maker. Making a bad situation worse, her confidence is catching: Through an eerie, fatalist game of telephone, her friends and family, and even total strangers with whom they interact, come to believe they’re going to die tomorrow, too. It’s almost like they’ve been gaslit, except they’re the ones soaking themselves with lighter fluid, sparking off a chain reaction of macabre determinism in which each person afflicted by the curse of languages sees the end coming for them in 24 hours or less. She Dies Tomorrow is both the perfect film for this moment and also the worst viewing choice possible considering the circumstances: Everyone’s at home, contending with varied combinations of dread, grief, rage of either the defiant or impotent persuasion, boredom and, in the absolute best case scenario, a numbing calm. Amy Seimetz, writing and directing her sophomore follow-up to her superb 2012 feature debut Sun Don’t Shine, captures the same pandemic fears as movies like Sea Fever and The Beach House, but enhances them with existential currents. Seimetz straddles the line dividing terror from malaise delicately, her balancing act being She Dies Tomorrow’s greatest strength. Instead of shoehorning all of her ideas and textures into one genre, she keeps the film fluid.—Andy Crump

37. Together Together

Year: 2021

Directors: Nikole Beckwith

Stars: Patti Harrison, Ed Helms, Rosalind Chao, Tig Notaro, Fred Melamed, Julio Torres

Rating: R

Together Together is an amiable, successfully awkward surrogacy dramedy that also has the respectable distinction of being a TERF’s worst nightmare. That’s only one of the tiny aspects of writer/director Nikole Beckwith’s second feature, but the gentle tapestry of intimacy among strangers who, for a short time, desperately need each other certainly benefits from the meta-text of comedian and internet terror Patti Harrison’s multi-layered starring performance. Stuffed with bombastic bit parts from a roster of recent television’s greatest comedic talents and casually incisive dialogue that lays waste to media empires and preconceptions of women’s autonomy alike, the film is an unexpected, welcome antidote to emotional isolation and toxic masculinity that meanders in and out of life lessons at a pleasingly inefficient clip. That the tale of fatherhood and friendship is told through the sparkling chemistry of a rising trans star and her entrenched, anxious straight man (an endearing Ed Helms) only adds to Together Together’s slight magic.—Shayna Maci Warner

38. Pig

Year: 2021

Director: Michael Sarnoski

Stars: Nicolas Cage, Alex Wolff, Adam Arkin

Rating: R

In the forest outside Portland, a man’s pig is stolen. Rob (Nicolas Cage) is a witchy truffle forager that we learn used to be a chef—a Michelin-starred Baba Yaga, a gastronomical Radagast—who sells his pig’s findings to sustain his isolated life. What follows is not a revenge thriller. This is not a porcine Taken. Pig, the ambitious debut of writer/director Michael Sarnoski, is a blindsiding and measured treatise on the masculine response to loss. Featuring Nicolas Cage in one of his most successful recent permutations, evolving Mandy’s silent force of nature to an extinct volcano of scabbed-over pain, Pig unearths broad themes by thoroughly sniffing out the details of its microcosm. The other component making up this Pacific NW terrarium, aside from Rob and the golden-furred Brandy’s endearingly shorthanded connection, is the guy Rob sells his truffles to, Amir. Alex Wolff’s tiny Succession-esque business jerk is a bundle of jagged inadequacies, and only Rob’s calloused wisdom can handle such prickliness. They’re exceptional foils for one another, classic tonal opposites that share plenty under the surface of age. Together, the pair search for the pignapping victim, which inevitably leads them out of the forest and back into the city. There they collide with the seediest, John Wick’s Kitchen Confidential kind of industry underbelly you can imagine, in a series of standoffs, soliloquies and strange stares. It’s a bit heightened, but in a forgotten and built-over way that feels more secret than fantastic. The sparse and spacious writing allows its actors to fill in the gaps, particularly Cage. Where some of Cage’s most riveting experiments used to be based in manic deliveries and expressionistic faces, what seems to engage him now is the opposite: Silence, stillness, realist hurt and downcast eyes. You can hear Cage scraping the rust off Rob’s voice, grinding the interpersonal gears much like the dilapidated truck he tries (and fails) to take into town. Wolff, along with much of the rest of the cast, projects an intense desperation for validation—a palpable desire to win the rat race and be somebody. It’s clear that Rob was once a part of this world before his self-imposed exile, clear from knowing gazes and social cues as much as the scenarios that lead the pig-seekers through basements and kitchens. Part of Pig’s impactful, moving charm is its restraint. It’s a world only hinted at in 87 minutes, but with a satisfying emotional thoroughness. We watch this world turn only slightly, but the full dramatic arcs of lives are on display. A sad but not unkind movie, and certainly not a pessimistic one, Pig puts its faith in a discerning audience to look past its premise.—Jacob Oller

39. Nomadland

Year: 2020

Director: Chloé Zhao

Stars: Frances McDormand, David Strathairn, Linda May, Swankie, Bob Wells

Rating: R

A devastating and profound look at the underside of the American Dream, Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland turns Jessica Bruder’s non-fiction book Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century (and some of its subjects) into a complex folk song about survival, pride and the beauty of getting by on the open road. Focusing on older Americans who’ve somehow either abandoned or been forced from stationary traditional homes into vans and RVs, the film contemplates all that brought them to this point (an ugly, crammed Amazon warehouse looms large over the movie’s otherwise natural landscapes and sweeping vistas) and all that waits for them now that they’re here. Some of Bruder’s sources make appearances in the film, threatening to steal the show from the fictional Fern (Frances McDormand) at every turn—and McDormand turns in one of the best performances of the year. That’s just how honest and compelling Linda May and Swankie are. As the migrating community scatters to the wind and reconvenes wherever the seasonal jobs pop up, Zhao creates a complicated mosaic of barebones freedom. It’s the vast American landscape—a “marvelous backdrop of canyons, open deserts and purple-hued skies” as our critic put it—and that mythological American promise that you can fend for yourself out in it. But you can’t, not really. The bonds between the nomads is a stiff refutation of that individualistic idea, just as Amazon’s financial grip over them is a damnation of the corporation’s dominance. Things are rough—as Fern’s fellow travelers tell campfire tales of suicide, cancer and other woes—but they’re making the best of it. At least they have a little more control out here. The optimism gained from a reclaimed sense of autonomy is lovely to behold (and crushing when it comes into conflict with those angling for a return to the way things were), even if its impermanence is inherent. Nomadland’s majestic portrait puts a country’s ultimate failings, its corrupting poisons and those making the best of their position by blazing their own trail together on full display.—Jacob Oller

40. Parallel Mothers

Year: 2021

Director: Pedro Almodóvar

Stars: Penélope Cruz, Milena Smit, Israel Elejalde, Rossy de Palma, Aitana Sánchez-Gijón

Rating: R

Set in 2016, Parallel Mothers follows Janice (Penélope Cruz), a professional photographer in her 40s who begins a casual fling with forensic anthropologist Arturo (Israel Elejalde). Nine months after a particularly steamy encounter, she checks herself into a Madrid hospital’s maternity ward, preparing to give birth and raise her child as a single mother. As fate would have it, her roommate is in a similar position, save for the fact that she’s over 20 years Janice’s junior: Ana (newcomer Milena Smit) is also without a partner, her only support during labor being her self-absorbed actress mother (Aitana Sánchez-Gijón). While Janice is thrilled that she’s been given the impromptu opportunity to become a mother, Ana is initially resentful of the circumstances that have led to her pregnancy. Yet the two women quickly bond, taking strolls down the sterile hospital halls in order to help their babies descend down the uterus. Coincidentally, they both give birth to beautiful baby girls, and exchange numbers in order to keep in touch as they embark on the journey of newfound motherhood. Though the film sets itself up as an straightforward examination of the peculiar perils of parenthood—particularly for women who raise children outside of the confines of conventional, heterosexual nuclear families—Pedro Almodóvar instead utilizes multiple generations of matriarchs to bring light to the families irreparably broken by the cruelty of Spain’s not-so-distant fascist regime. The initial reason why Janice approaches Arturo is to inquire if he could use his connections to organize an excavation of a mass grave in her hometown—one of the bodies buried being that of her great-grandfather. In many ways, Parallel Mothers is also an atonement on Almodóvar’s part for his own distancing from this period of Spain’s history, particularly considering that his own film career flourished after Franco’s decline. For a director who has never shied away from portraying society’s most controversial taboos on-screen—incest, rape, suicide attempts, pedophilia and even golden showers—the fact that it has taken him his entire career to explicitly incorporate the effects of the Spanish Civil War into his work demonstrates the country’s relative inability to reckon with it. Though Almodóvar has stated that none of his own family members were victims of fascist brutality, his dedication to the ongoing plight of the families of those who perished infuses the film with an almost uncharacteristic sense of levity and sorrow. While this is certainly a shift in the filmmaker’s melodramatic and outlandish sensibilities (though this has been shifting significantly since his 2019 semi-autobiographical Pain and Glory, followed by the deconstructive short The Human Voice), it never feels mishandled in his grasp, always remaining sensitive even while incorporating shocking twists and revelations. Particularly paired with Cruz’s knockout performance of a woman whose life endures the legacy left by the trauma of her family’s unresolved past, Parallel Mothers is a deeply political example of what is lost when we have forgotten—and what is achieved when we fight to remember.—Natalia Keogan

41. The Northman

Year: 2022

Director: Robert Eggers

Stars: Alexander Skarsgård, Nicole Kidman, Claes Bang, Anya Taylor-Joy, Ethan Hawke, Willem Dafoe, Björk

Rating: R

Forged in flame and fury, Robert Eggers’ The Northman is an exquisite tale of violent vengeance that takes no prisoners. Co-written by Eggers and Icelandic poet Sjón (who also recently co-wrote A24’s Icelandic creature feature Lamb), the film is ever-arresting and steeped in the director’s long-standing penchant for period accuracy. Visually stunning and painstakingly choreographed, The Northman perfectly measures up to its epic expectations. The legend chronicled in The Northman feels totally fresh, and at the same time quite familiar. King Aurvandill (Ethan Hawke) is slain by his brother Fjölnir (Claes Bang), who in turn takes the deceased ruler’s throne and Queen Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) for his own. Before succumbing to fratricide, Aurvandill names his young son Amleth (Oscar Novak) as his successor, making him an immediate next target for his uncle’s blade. Narrowly evading capture, Amleth rows a wooden boat over the choppy waters of coastal Ireland, tearfully chanting his new life’s mission: “I will avenge you, father. I will save you, mother. I will kill you, Fjölnir.” Years later, Amleth (played by a muscular yet uniquely unassuming Alexander Skarsgård) has distinguished himself as a ruthless warrior among a clan of Viking berserkers, donning bear pelts and pillaging a series of villages in a furious stupor. The Northman is an accessible, captivating Viking epic teeming with the discordant, tandem force of human brutality and fated connection. Nevertheless, it’s worth mentioning that the film feels noticeably less Eggers-like in execution compared to his preceding works. It boasts a much bigger ensemble, seemingly at the expense of fewer unbroken takes and less atmospheric dread. In the same vein, it eschews the filmmaker’s interest in New England folktales, though The Northman does incorporate Eggers’ fascination with forestry and ocean tides. However, The Northman melds the best of Eggers’ established style—impressive performances, precise historical touchstones, hypnotizing folklore—with the newfound promise of rousing, extended action sequences. The result is consistently entertaining, often shocking and imbued with a scholarly focus. It would be totally unsurprising if this were deemed by audiences as Eggers’ definitive opus. For those already enamored with the director’s previous efforts, The Northman might not feel as revelatory as The Witch or as dynamic at The Lighthouse. What the film lacks in Eggers’ filmic ideals, though, it more than makes up for in its untouchable status as a fast-paced yet fastidious Viking revenge tale. The Northman is totally unrivaled by existing epics—and perhaps even by those that are undoubtedly still to come, likely inspired by the scrupulous vision of a filmmaker in his prime.—Natalia Keogan

42. Moffie

Year: 2021

Director: Oliver Hermanus

Stars: Kai Luke Brummer, Ryan de Villiers, Matthew Vey, Stefan Vermaak, Hilton Pelser, Wynand Ferreira

“Moffie” is an Afrikaans slur, used to describe a gay man. For those of us who haven’t grown up hearing it, the term can read almost affectionate, its soft syllables suggesting a sweetness. In reality, there’s violence in the word, spat out with cruelty. This tension pervades the fourth film from Oliver Hermanus, regarded as one of South Africa’s most prominent queer directors. Moffie tells the story of Nicholas Van der Swart (Kai Luke Brümmer), a closeted 18-year-old drafted into his mandatory military service in South Africa in 1981, when the country was still in the throes of apartheid. Adapted from André Carl van de Merwe’s novel, Moffie tells a brutal tale with moments of beautiful respite. Despite the constant barrage of terrorizing drills and frat boy behavior, however, there is tenderness—like Nicholas’ connection with his rebellious squadmate, Dylan Stassen (Ryan De Villiers). An earlier incident makes it abundantly clear how dangerous it is to express any sort of affection. As a result, even the smallest gesture of intimacy is fraught with tension. Although the young men, shown in various forms of dress and undress, are strapping soldiers, there’s also a vulnerability to them. You can’t help but silently cheer, even as your heart breaks a little, when Nicholas and Michael break into a muted rendition of “Sugarman,” giggling as they clean their rifles. Despite the army’s best efforts to break the young men, their spirits seem to survive. Despite the heavy load it carries, Moffie is a masterful film. Hermanus and Jack Sidey have co-written a tight script, with stretches of silences that pull you into the internal struggles of its characters. The cinematography by Jamie D Ramsay ranges from languorous shots of the rugged, dusty landscapes where the recruits carry out drills in the harsh sun to the handheld immediacy of Nicholas and his fellow soldiers’ misery. The cast—made up of a mix of high school students, trained actors and non-professionals—manages to conjure up a chapter of South African history that many would like to forget.—Aparita Bhandari

43. Black Dynamite

Year: 2009

Director: Scott Sanders

Stars: Michael Jai White, Byron Minns, Tommy Davidson, Kevin Chapman

Rating: R

It may seem to be a bit late to spoof the blaxploitation films of the 1970s, but don’t tell the guys who made Black Dynamite. Scott Sanders, Michael Jai White and Byron Minns have made a funny satire whose distance from the source material works to its advantage. It pulls its style from films like Shaft and Coffy, using a low-grade film stock, polyester clothing, and afro wigs to mimic their textured look, but it pulls most of its humor from the same vein of silliness that produced movies like Airplane!, expecting an audience that responds to absurdity, not movie allusions. Even if your nearest exposure to Foxy Brown is through a Quentin Tarantino homage, Black Dynamite likely has a joke aimed at you.–Robert Davis

44. Sorry We Missed You

Year: 2020

Director: Ken Loach

Stars: Kris Hitchen, Debbie Honeywood, Rhys Stone, Katie Proctor, Ross Brewster, Charlie Richmond, Sheila Dunkerley

Ken Loach’s movies typically force viewers to acknowledge the toll a job can take on both body and spirit. Without fuss or forced moralizing, Sorry We Missed You performs this service for the folks who thanklessly zip about town dropping off parcels ordered yesterday by people who actually needed them a week before. The movie demystifies the browser sorcery of one-click purchases by humanizing, for better and for worse, the mechanics behind this modern-day ministration: Loach starts with Ricky (Kris Hitchen), head of the Turner family, who is first met interviewing Maloney (Ross Brewster), his boss-to-be, for a post as an owner-driver for a third-party delivery outfit nestled in North England. Maloney seems reasonable enough. He hears Ricky’s story, at least, his history as a blue-collar man whose years of hard labor have left him craving for freedom from micromanaging bosses. Ricky wants to be his own boss now, and Maloney’s spiel about choice and self-agency appeals to his wants. It’s all an illusion, of course, and the economy of Laverty’s writing succinctly lays out the tension between Ricky’s ambitions and the crushing realities of the position he’s sought out. The gift of personal determination Maloney offers him is a Trojan horse containing seeds of poverty. The way this job works, every package Ricky hands off is another row sown in his inevitable destitution. It’s sick. It’s barbaric. It’s just one problem among several the Turners deal with as a direct consequence of Ricky’s enterprise. He has to sell off, for instance, the family car, which his wife, Abbie (Debbie Honeywood), uses for her own career as a home care nurse, which means she has to use public transportation, which is another stress added to an already stressful job made more stressful by her boss, who like Maloney doesn’t really give a damn about Abbie as a person—only as a hireling. Sorry We Missed You operates on a micro-level with contrastingly astronomical stakes. It’s a movie about one small family—including, apart from Kris and Debbie, their mulish teen son, Seb (Rhys Stone), and younger, sweethearted daughter, Liza Jane (Katie Proctor)—doomed to the streets if either Dad or Mom missteps. They have no safety net. They have no contingency plan. Worst of all, Kris and Debbie both have jobs designed to wring the most out of them with the least compensation or compassion in exchange. The perils of parenthood are enough without having to answer the question of how the lights stay on every day. —Andy Crump

45. Top Gun: Maverick

Year: 2022

Director: Joseph Kosinski

Stars: Tom Cruise, Jenifer Connelly, Miles Teller, Jon Hamm, Monica Barbaro, Ed Harris, Val Kilmer, Jay Ellis, Glen Powell, Lewis Pullman, Danny Ramirez, Greg “Tarzan” Davis

Rating: PG-13