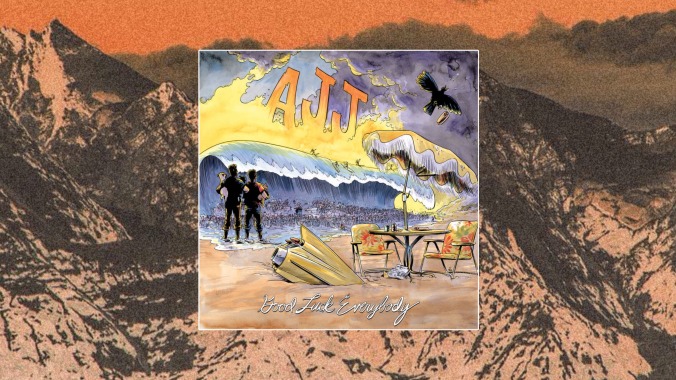

A Decade Half-Spent: AJJ’s Good Luck Everybody

We’re paying tribute to our favorite albums of the 2020s so far with a series of essays.

We are deep in the final dregs of 2024, which means, terrifyingly, that in just a few days we will hit the halfway mark of the decade—and, perhaps even more terrifyingly, that the onset of COVID-19 was almost five whole years ago. I’ve never been great at grappling with the passage of time but, for some reason, that fact, even more than most, feels nearly incomprehensible. How can it possibly be almost five years since quarantine? How can it possibly be five years since all of us privileged non-“essential workers” desperately searched for purpose inside batches of sourdough starter, since we all watched Tiger King for some reason and got weirdly into the idea that everything was cake?

How can it possibly be five years since I sat in my childhood home in Tallahassee and brute-forced my way into learning how to do alt-TikTok-style eyeliner for my Zoom prom (I wish I was kidding) while binging Game of Thrones and watching my notifications pile high with men demanding I kill myself (because I inexplicably went mini-viral for a random TikTok video)? How can it possibly be five years since the only semblance of schedule and routine I had in my life was hopping on Instagram at 10:30 PM EST to watch AJJ’s Sean Bonnette live-stream free, half-hour-long concerts every night, since my only semblance of community was rapidly double-tapping my phone screen when Bonnette played the opening chords of a Silver Jews cover song and watching my pixel hearts intermingle with everyone else’s, floating upwards in unison?

There are very few memories I have of quarantine that don’t make me violently cringe, but looking back on Bonnette’s nightly (eventually turned weekly) “Live from Quarantine” streams only elicits genuine fondness and gratitude even now, years down the line. AJJ’s predominance in my life at that time wasn’t just due to those nightly concerts, either—the band’s January 2020 release Good Luck Everybody would likely have served as the soundtrack for my first few months of lockdown regardless. Not only was the record one of the last releases to catch my eye before everything went to shit, but, as days in quarantine turned into weeks and then months, Good Luck Everybody went from a solid record fueled by 2019 anger to an eerily prescient encapsulation of the months, even years, that followed its release.

Because, before the indie albums that came to define the COVID-consumed fever dream that was 2020 (like Fiona Apple’s Fetch the Bolt Cutters and Jeff Rosenstock’s No Dream), there was still that first and worst month of quarantine, those four or so weeks that passed by while we moved from miserable and confused to desperate and fearful—into that sunken state of bored complacency with the new dystopian state of reality. But during that time there was also, thankfully, Good Luck Everybody, which somehow perfectly evoked the muted hopelessness, pervasive isolation and gradually normalized despair of life during a global pandemic (a pandemic that, obviously, AJJ’s January album could not have possibly predicted).

In other words, between the album itself and Bonnette’s nightly performances of its tracklist, I found myself clinging to Good Luck Everybody during that first month stuck at home. I know I wasn’t the only one, either; there’s a reason a few hundred of us tuned in every night to watch Bonnette sit on a black stool and sing to the people trapped behind their phone screens. But when Bonnette wrote the lines “Everything’s bullshit now, here in 2019 / And you can bet it’s gonna be a bunch of bullshit, too, out in sweet 2020 / Or whenever this album’s released” on the album’s excellent closer, “A Big Day for Grimley,” it’s a pretty safe bet that the kind of “bullshit” he was referring to had more to do with the winding days of Donald Trump’s first presidential term and police brutality than a global pandemic shutting down the entire world for months on end—but the shoe certainly fits either way. Good Luck Everybody was so jarringly resonant during the quarantine months that the band themselves have commented a few times about the uncanniness of it all. As cellist Mark Glick quipped in 2023: “I do want to go on record that we did not engineer COVID as a marketing stunt for Good Luck Everybody.”

Despite its unexpected resonance with the very near future, the record was undeniably about the (very recent) past. Good Luck Everybody was written, certainly, as a response to 2019, as well as the previous four years in general—and, honestly, the fact that an album about 2019 ended up speaking so much to the experience of living in fear of a virtually unprecedented international pandemic really says something about the awfulness of the years that led up to it. A majority of the tracks on the album revolve around Bonnette’s growing horror toward the state of American politics (especially Trump, who is all but explicitly named in these songs) as well as our ever-increasing desensitization to the constant stream of atrocities that quickly came to define the Trump era.

Some of it does fall a little flat, the lyrics feeling a tad too-on-the-nose, especially in hindsight (while they’re still decent songs, the balladic “No Justice, No Peace, No Hope” and the furious “Psychic Warfare” do come to mind). But some of the album still works incredibly well, as evidenced in tracks like “Loudmouth” and “Normalization Blues,” both of which are pitch-perfect encapsulations of (and self-aware critiques from within) the political zeitgeist of the time. And I can’t forget the Twitter-inspired, Kimya Dawson-featuring, oddball pseudo-campaign anthem of “Mega Guillotine 2020” and its children’s show sing-along style music video (which features the severed, bloodied heads of prominent politicians floating through a Teletubbies-esque world), a combination so ridiculous and ballsy that it’s been my go-to election song ever since.

One of Bonnette’s greatest strengths as a songwriter has always been his ability to spin his own experiences and internal monologues into deeply personal yet universally resonant narratives—to turn his own self-flagellating self-consciousness into far-reaching diagnoses of a struggling culture, without veering into didactic or prescriptive territory—and this skill is on full display in both “Loudmouth” and “Normalization.” Rather than attacking our political moment itself (as he does in “No Justice” and “Psychic Warfare,” which are very much direct addresses to our leaders and their monstrous actions and policies), these tracks embody the experience of living within it, the ways the daily horrors bleed into us and make us complacent, make us callous. They combine Bonnette’s signature self-awareness with trenchant political critique, and are undoubtedly stronger for it.

There are few songs that encapsulate the state of online discourse as well as the spirited, rollicking “Loudmouth,” which just about sums up every Twitter argument with its immortal opening lines: “You’re a loudmouth and a tool / And I don’t disagree with you / But you don’t need to be a dick about it.” But the song ends up being far less about the “you” than the speaker themself; it even ends with a slightly-altered reprisal of the opening, in which the speaker admits that while the subject is “a loudmouth and a tool,” “It turns out I am, too.” Bonnette implies that much of “the discourse” serves as a convenient substitute for actual action or change; we need to direct all our pent-up anger and fear and disgust somewhere, and semi-anonymous idiots are far more accessible targets than the masters of war and captains of industry. “Timid, meek, and cruel, this is the best that I can do,” Bonnette sings. “I need to speak my truth, yet here I’m broken wide, wide open.” He drives the point home in the bridge: “My resentment, big and strong / And all the things that I can’t change / They’ll buckle me beneath the weight / I will drive myself insane / With all the things that I can’t change.”

Bonnette knows that it feels easier to fight amongst ourselves, because we are actually here to fight against, than to direct our rage uselessly towards the untouchable-seeming powers that be. But, as he sings earlier in the record, on “Normalization Blues,” this is just proof that said powers not only “try to divide us” but are “largely…succeeding / ‘Cause they’ve undermined our confidence in the news that we are reading / And they make us fight each other with our faces buried deep inside our phones.” It’s the fault of those in charge, of course, but we also play right into their hands, and we spend so much time running our loud mouths at each other that we can’t even bring ourselves to see that, let alone take communal action—communal action such as, for instance, refusing to give celebrities our money, attention, and all our love, as Bonnette (and Jeff Rosenstock, who provides guest vocals) points to in the opening track, “A Poem”: “If you don’t give it to them they’ll starve to death / And that’s alright.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-