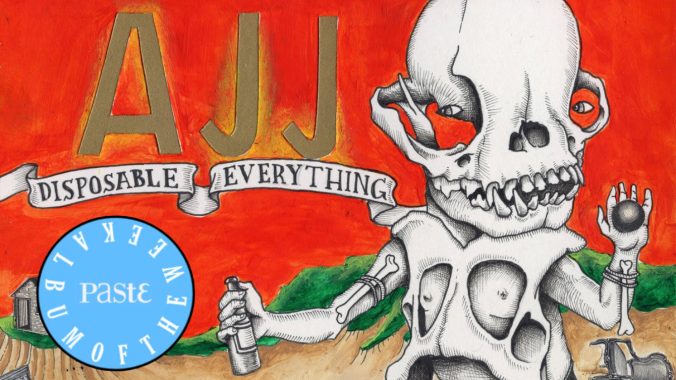

Album of the Week: AJJ – Disposable Everything

On their best project in 12 years, the Phoenix quintet grow older, wiser and more cynical in the face—and wake—of ecological and societal collapse

AJJ’s newest album, Disposable Everything, bends beneath the weight of everything around the planet being fucked beyond repair. The gerbil in the microwave has exploded into a cataclysmic shift aiming to split the United States in half! After the mess of 2016 and its sequel four years later, the leading voices in folk-punk—five storytellers who sought to break down the systems of hedonistic masculinity that fueled disasters, wars, racism and douchery—were forced to reconfigure just how much space they should, or could, give to their versions of villains inflicting real, generational trauma on marginalized people in their songs.

The difference a decade can make is colossal: Not even a score ago, AJJ made music as Andrew Jackson Jihad and sang lyrics like this: “But there’s a bad man in everyone / No matter who we are / There’s a rapist and a Nazi living in our tiny hearts / Child pornographers and cannibals, and politicians, too / There’s someone in your head waiting to fucking strangle you.” When I came across the Phoenix quintet’s (Sean Bonnette, Ben Gallaty, Preston Bryant, Mark Glick and Kevin Higuchi) music on a random Pandora station a dozen years ago, it didn’t feel edgy so much as a lesson I didn’t quite have the capacity to understand yet. I didn’t know that the lines Bonnette sang were not endorsements but, rather, fast critiques and satirization of the bad brutes employing inequity, poverty, homophobia and misogyny on the world around us.

A song like “People II: The Reckoning” is painfully relevant now, and I remember a time when dudes would go to AJJ shows and be too vicious in the pits—merciless to their fellow men (but mostly women) to the point where the band would call them out for their behavior, as those menaces in the audience were flirting with the scumbag mentalities that they’d bought tickets to hear frontman Bonnette and company sing about. AJJ’s sophomore album People Who Can Eat People Are the Luckiest People in the World, now almost 16 years old, was a mixture of bullying deadbeats through high-brow, gutter-rat poetics and genuine, empathetic extensions of love to the people often under the boot of loudmouths who reveal their true colors and aggressions once the loud, in-your-face music starts.

Back then, we all found joy in singing “there’s a bad man in everyone” loud and proud, regardless of if we were clear-eyed teenagers, foul-mouthed pricks or stuck in the purgatory of grayness somewhere in-between. To be evil, figuratively or literally, felt like a fate that couldn’t be so bad, especially if it meant getting immortalized in the brash sing-song of AJJ and other folk-punk troubadours forever. In retrospect, I—and my raucous comrades—probably should have sung “People are people regardless of skin / People are people regardless of creed / People are people regardless of gender / People are people regardless of anything” louder.

Thankfully, I have grown up and lived to see the day of Disposable Everything, AJJ’s first album in three years—a follow-up to their uneven 2020 LP Good Luck Everybody. The latter wasn’t a bad record by any means, but it felt like the eras of Knife Man and Can’t Maintain—two of the best albums, across any genre, from the last 15 years—were fully gone. For the most part, AJJ had mellowed out on Good Luck Everybody, though the album closer “A Big Day for Grimley” eerily predicted the fallout of 2020, COVID-19, presidential election and all. “Now I don’t suffer any more bullshit gladly / Even though everything’s bullshit now, here in 2019 / And you can bet it’s gonna be a bunch of bullshit, too, out in sweet 2020,” Bonnette sang.

Fast-forward three years and here we are, on the precipice of nothing getting better. And AJJ know that truth, too. Disposable Everything is a big reconciliation with the current state of affairs and the band’s place in all of it. What role should five men have in preserving any semblance of goodness that might still be left in this country? On Disposable Everything, AJJ aren’t quite sure they should have a role at all. In a world plagued by mainstream artists attempting to spin shallow money-grabs into wholehearted, political decrees, AJJ are not all that interested in shining the empathy on in ways they cannot authentically provide. There is no demand for revolution on this album; only the stark realization by the men who made it that they, too, have been lubing the cog that makes the machine of inequity crawl forward.

“Dissonance” gnaws away at that notion immediately. Bonnette says “solidarity forever, man” before cascading into his own musings: “My feet planted in different realities / I’ve been doing lots of parallel planning and asking / ‘Does morals exist anymore?’ / Wondering if society’s all broken down yet,” he sings, until brazenly segueing into a plainspoken “I should probably know.” No one needs a man to go on some poetic ramble about how they are attempting to dismantle their own privilege. What’s refreshing about AJJ’s approach is that they don’t offer up an answer. Whether it’s because they don’t have one or they aren’t looking to pull up a chair to that table or both, sometimes it’s good to write a song that doesn’t check every box. To get older is to understand that life doesn’t work that way, and that any semblance of resolve can, potentially, be eons away. AJJ are still growing up, but they are much wiser now than they were 15 years ago. The things they satirically and cheekily sang about in 2007 have become painful realities, and they’ve now opted to reflect on it rather than further embellish it.

“This is no exaggeration / We’re living in a death machine,” Bonnette sings at the opening of the rowdy “Death Machine.” The song finds him reflecting on the AJJ of old, what the songs from The Bible 2 and Christmas Island and Rompilation were about and how they even matter in the context of 2023. “This ain’t no call to action / Can’t get no satisfaction, not even sure what I was trying to sing / But at least until it stops existing, this fucking time bomb keeps ticking,” Bonnette laments. If you are old enough to remember when AJJ’s nihilistic, violent lyrics critiqued the world we lived in—rather than operate like some uncanny parallel to the catastrophe that became reality—you might have wondered how a band with an aesthetic of immense envelope-pushing could ever survive in a landscape like this one. The answer is simpler than you might expect; AJJ stuck to their guns and stayed true to themselves, with a new coat of hindsight glazed atop their performances.

I am often uninterested in the current state of folk-punk. Many of its purveyors straddle the middle-line, unbothered to sink their teeth on any conscientious articulations of the ass-backwards American milieu they feast on the riches of. There’s a reason the zeitgeist has forgotten about them: How do you have the gall to workin within a genre with roots that began in political songwriting generations ago and perform with such dodginess? I’m not saying music can save the world; we’re much too far gone for that. But, there’s only so many ways you can possibly sing about a relationship—while also giving the finger to the disparity unleashing havoc on the people around you—before it all gets too trite. I’m sure AJJ could’ve turned this 14-song LP into a full-blown, no-punches-pulled barn-burning. I trust Bonnette to do it right, but what would a project of that scope achieve? Instead, the band doesn’t overstay their welcome and saturate Disposable Everything by shilling too much of a vain pedagogy that would obliterate the margins they’re supposedly looking out for.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-