Patterson Hood On Town Burned Down, A Resurrected Record

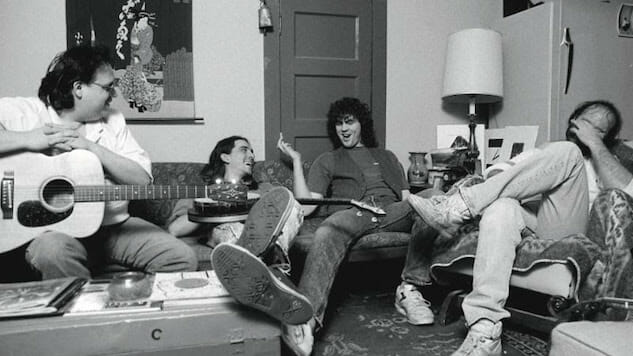

Images via the artist, Jason Merritt/Getty Music Features Patterson Hood

The story of Town Burned Down, an album exiled to almost three decades of musical purgatory, is a miraculous one.

It starts with two friends-turned-roommates (turned-bandmates), Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley, who you know from Drive-By Truckers, the now-acclaimed southern rock band they formed in Athens, Ga., in 1996. But before the Truckers, they were two kids living in Florence, Ala., cranking out searing, soaring country punk under another handle: Adam’s House Cat, named for the oddball southern colloquialism, “I wouldn’t know him from Adam’s house cat.” On Nov. 25, 1990, Hood and Cooley, along with their drummer Chuck Tremblay and bassist John Cahoon, recorded what would later—much later—become Town Burned Down. They tracked 15 songs in one day, in what Hood describes as a “cavernous” room above the famed Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. But the band broke up before securing any kind of record deal.

Now, Town Burned Down is emerging from the ashes as a proper release on ATO Records (out Sept. 21). It’s a miracle album, prevailing despite a timeline dotted with death and natural disasters (which Hood extensively details in the album’s liner notes): The original Town Burned Down tapes were shipped off to a studio in Jackson, Miss., where they were later destroyed in a tornado. Cahoon committed suicide in 1999. And last summer, Tremblay nearly died after suffering a heart attack. Luckily, Tremblay has since made a full recovery and, in 2015, producer David Barbe unearthed a box of long, lost Adam’s House Cat tapes from the depths of his Athens studio. Hood returned to Athens to re-record the vocal tracks, which, in the spirit of Adam’s House Cat, he did in just two hours. Town Burned Down will now finally see the light of day.

“It has always kind of eaten at us that that record never came out,” Hood said. “It was something we did that we were super proud of that we worked really hard on, and then just as we were finishing, fate kinda interfered and the band broke up and it never came out.”

Hood, then freshly 21, met a 19-year-old Mike Cooley in August of 1985 because he needed a place to live, and Cooley had extra space in his dank basement. They found Tremblay via a bulletin board at a music store. “Chuck was in his thirties and was this really cool sweet older guy who was an amazing drummer who basically taught a bunch of punk kids how to be a rock ’n’ roll band,” Hood said.

Muscle Shoals might have a reputation for boosting great rock ’n’ roll bands to stardom, but in the late ’80s, the region was hurting for original acts. Adam’s House Cat kicked up some momentum as a band touring the Southeast, frequenting holes-in-the-wall like The Nick in Birmingham, Ala., and bars in Oxford and Nashville, but they never found their footing at home. Too punk for the country bars and too country for the college bars, Adam’s House Cat were in limbo.

“There weren’t many people coming to record there and a lot of the musicians moved off, my dad being one of the holdouts that didn’t,” Hood says. “And for those who stayed, it was rough. It was really hard. When we started out we were literally the only band in town playing original music, and we were kinda hated for it.”

Of course, Muscle Shoals and Florence have since resurged as the musical powerhouses they once were in the ’60s and ’70s, boasting booked studios and artists like Jason Isbell and Alabama Shakes (not to mention a very well-received music documentary). But back then, Muscle Shoals was just like many small, Southern towns—isolated. Town Burned Down, at its very core, is a record about being stuck somewhere and wanting to get out, a product of angry young men feeling trapped. Hood threatens to pitch himself off “Lookout Mountain” or jump on a “6 O’Clock Train” heading east—anything to get out of “Buttholeville.”

“I’ve caught a lot of hell on [“Buttholeville”],” Hood says. “People interpret that song as being about the town, but it’s really about a state of mind that was pretty prevalent in that town and probably most small towns, places where most people grow up. And I was young and punk rock enough to kind of run with that and stick my middle finger up about that whole thing.”

“Buttholeville” is a prime example of Hood’s and Cooley’s glaring, unruly discontent, but, listening almost 30 years after its original recording, it doesn’t sound too hot-headed for its own good. To anyone who’s lived in a stifling small town, it’s just relatable. Hood defiantly yells, “One day I’m gonna get out of Buttholeville/ Gonna reach right in/ Gonna grab the till.”

As frustrating as it was to inhabit these small, smelly spaces, Adam’s House Cat’s position allowed them the opportunity and fervor to make great punk rock music. Town Burned Down isn’t punk in the purist sense—there’s often more twang than a traditionally punk song allows. But it’s rebellious in its own way, a flurry of upset guitar, thrashing drums and Hood’s distinct, often angry, drawl. Listening in 2018, you might recognize that its sweltering rock fits right in with the fringe movements of the ’80s and ’90s. Hood cites college rock and punk as massive influences on Adam’s House Cat.

“The Clash is still probably my all time favorite rock ’n’ roll band, and The Replacements were a huge band to me and were a huge influence on the beginning of Adam’s House Cat,” he says. And R.E.M.—I’m still a massive R.E.M. fan. And that was one of the things that really kind of took us back when we listened to these tapes after all these years, was just how big the R.E.M. influence was, how blatant the R.E.M. influence was.”

While Town Burned Down’s anecdotes feel more personal than political, the Drive-By Truckers went on to become fierce fighters for social justice, both within and outside their music. Hood has penned politically-charged essays for sites like The Bitter Southerner, and the band’s twitter account frequently encourages voter registration in Alabama and beyond. The Truckers’ 2016 album American Band, was a protest record, and “What It Means” a blistering anthem written in response to the police shootings of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown. Town Burned Down isn’t so overt, but Hood says they were just as politically minded then as they are now.

“It’s funny because Adam’s House Cat had a number of songs that are probably more blatantly political than songs on [Town Burned Down],” Hood says. “We were definitely a very thundernose kind of band, and I think that spirit still survives in what we do and think. We’ve probably gotten more nuanced in how we articulate things because we’ve gotten older and you tend to embrace nuance as you get older, maybe. When you’re younger you just wanna break shit, which is fine too. But between who we were and who we became, it’s not a radical difference.”

Hood says of all the music he’s made, with the Truckers and Adam’s House Cat, Town Burned Down is the favorite among his kids. His nine-year-old son frequently requests to heart it at their family home in Portland, Ore.

“He’s like, ‘I think that’s the best thing you’ve ever done Dad.’ I’m not sure how I feel about the best thing I’ve ever done being 30 years old, but I’m glad there’s something I’ve done he likes.”

Despite having been dormant for nearly three decades, the music of Town Burned Down feels deeply resonant in 2018. It may be the favorite of Hood’s children, and it certainly evokes youthful angst, but it’s ageless rock music.

“There’s some kid here today in some town he can’t wait to get the fuck out of,” Hood says. “And people still get their hearts broken. People still get shit on and all the different things that inspired the various songs on that record still happen to people.”