Patterson Hood On Town Burned Down, A Resurrected Record

Images via the artist, Jason Merritt/Getty

The story of Town Burned Down, an album exiled to almost three decades of musical purgatory, is a miraculous one.

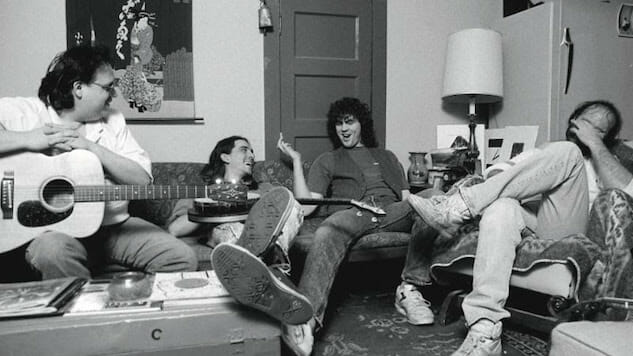

It starts with two friends-turned-roommates (turned-bandmates), Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley, who you know from Drive-By Truckers, the now-acclaimed southern rock band they formed in Athens, Ga., in 1996. But before the Truckers, they were two kids living in Florence, Ala., cranking out searing, soaring country punk under another handle: Adam’s House Cat, named for the oddball southern colloquialism, “I wouldn’t know him from Adam’s house cat.” On Nov. 25, 1990, Hood and Cooley, along with their drummer Chuck Tremblay and bassist John Cahoon, recorded what would later—much later—become Town Burned Down. They tracked 15 songs in one day, in what Hood describes as a “cavernous” room above the famed Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. But the band broke up before securing any kind of record deal.

Now, Town Burned Down is emerging from the ashes as a proper release on ATO Records (out Sept. 21). It’s a miracle album, prevailing despite a timeline dotted with death and natural disasters (which Hood extensively details in the album’s liner notes): The original Town Burned Down tapes were shipped off to a studio in Jackson, Miss., where they were later destroyed in a tornado. Cahoon committed suicide in 1999. And last summer, Tremblay nearly died after suffering a heart attack. Luckily, Tremblay has since made a full recovery and, in 2015, producer David Barbe unearthed a box of long, lost Adam’s House Cat tapes from the depths of his Athens studio. Hood returned to Athens to re-record the vocal tracks, which, in the spirit of Adam’s House Cat, he did in just two hours. Town Burned Down will now finally see the light of day.

“It has always kind of eaten at us that that record never came out,” Hood said. “It was something we did that we were super proud of that we worked really hard on, and then just as we were finishing, fate kinda interfered and the band broke up and it never came out.”

Hood, then freshly 21, met a 19-year-old Mike Cooley in August of 1985 because he needed a place to live, and Cooley had extra space in his dank basement. They found Tremblay via a bulletin board at a music store. “Chuck was in his thirties and was this really cool sweet older guy who was an amazing drummer who basically taught a bunch of punk kids how to be a rock ’n’ roll band,” Hood said.

Muscle Shoals might have a reputation for boosting great rock ’n’ roll bands to stardom, but in the late ’80s, the region was hurting for original acts. Adam’s House Cat kicked up some momentum as a band touring the Southeast, frequenting holes-in-the-wall like The Nick in Birmingham, Ala., and bars in Oxford and Nashville, but they never found their footing at home. Too punk for the country bars and too country for the college bars, Adam’s House Cat were in limbo.

“There weren’t many people coming to record there and a lot of the musicians moved off, my dad being one of the holdouts that didn’t,” Hood says. “And for those who stayed, it was rough. It was really hard. When we started out we were literally the only band in town playing original music, and we were kinda hated for it.”

Of course, Muscle Shoals and Florence have since resurged as the musical powerhouses they once were in the ’60s and ’70s, boasting booked studios and artists like Jason Isbell and Alabama Shakes (not to mention a very well-received music documentary). But back then, Muscle Shoals was just like many small, Southern towns—isolated. Town Burned Down, at its very core, is a record about being stuck somewhere and wanting to get out, a product of angry young men feeling trapped. Hood threatens to pitch himself off “Lookout Mountain” or jump on a “6 O’Clock Train” heading east—anything to get out of “Buttholeville.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-