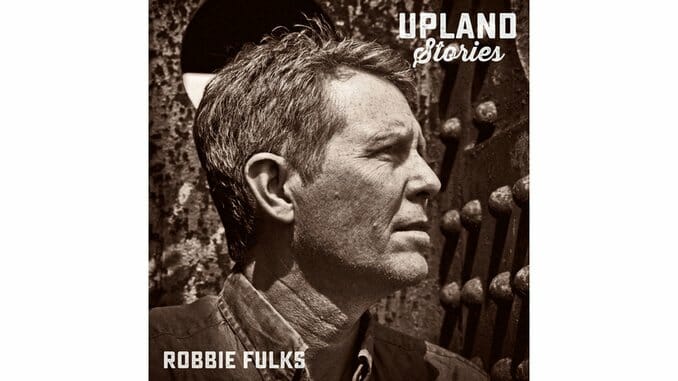

Robbie Fulks: Upland Stories

Before Sturgill Simpson or Chris Stapleton, there was Robbie Fulks: a hardcore alt-country sensation, writing subversive songs like his Nashville anti-Valentine “Fuck This Town,” “She Took A Lot of Pills (and Died)” and the religion-quaffing “God Isn’t Real.” With a Buck Owens Bakersfield beat, this was “punk goes old-school beer joint” with the audacity to throw down.

That Fulks didn’t ascend to Steve Earle or Lucinda Williams’ heights mystified those in the know. But in some ways, that’s not as mystifying as the angry young writer/hard country secessionist evolving to carve album arcs that draw upon Anton Chekov, Walter Agee or Javier Marias.

With his old-timey Upland Stories, Fulks matures into an important voice. Now seriously middle-aged, he comes into a deeper wisdom that allows merging the raw Appalachian holler of “America Is A Hard Religion”—as jolting from the honk of his turpentine-soaked bray as the truths he offers about the state of the nation—with the sweet acoustic “Baby Rocked Her Dolly,” a Currier & Ives etching of backwoods domestic ideals and the randy bluegrass strummer “Aunt Peg’s New Old Man” or the whispery love for “Sarah Jane.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-