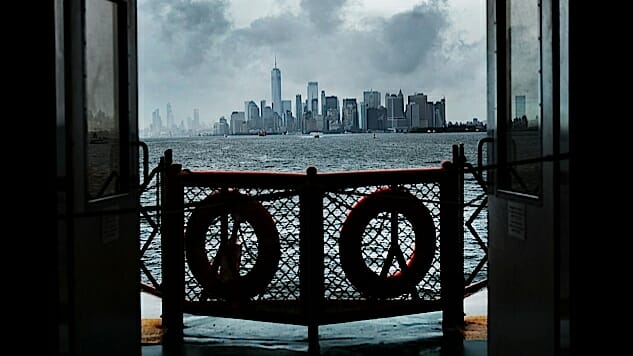

America’s Bleak “Tomorrow” Has Arrived. What Will We Do on the Day After?

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Politics Features climate change

Seventeen years ago this month, the Twin Towers fell. Fifteen years ago this month, we tried to set up the first post-Saddam government. Ten years ago this month, Wall Street collapsed. Fifteen months ago, Trump took us out of the Paris Climate Accord. This is not a story about endings, although it might read that way. This is a story about beginnings.

It’s common to complain about the future we were promised. You know the drill: Where’s my jetpack? Where’s my breakdancing robot? This is not my beautiful house! I bellow some version of these words almost daily.

Inevitably, during these rants, some pedant will point out that we already live in the future. It’s just distributed unevenly. Some people live in wired utopias of peace and plenty. During the ‘90s, the idea was simple: the technocracy would liberate us all. Sure, some of us had to wait a little longer for our holodeck, but it was in the cards.

Or so we thought. In 2018, the future really has arrived, and guess what? It’s not Tom Friedman’s storybook ending.

The most-quoted part of the bestselling Chapo Guide to Revolution: A Manifesto Against Logic, Facts, and Reason notes:

People talk about the “coming apocalypse.” Take a closer look. The apocalypse is Puerto Rico annihilated by a hurricane. It’s villages in India, Bangladesh, and Nepal tortured by lethal flooding. The apocalypse is already here; you just don’t live there yet.

Newsweek cites their argument:

After listing the consequences of rising worldwide temperatures—ocean acidification, sea-level rise, barren farmlands, water insecurity, devastating extreme weather, refugee crises, wars and “ancient comic-book-villain-origin-story-caliber diseases unearthed from melted permafrost”—the Chapo team concludes, “More than anything, though, the current situation demands a huge expansion of what is considered ‘realistic’ or possible.”

These past two weeks in particular, the signs are all around us. As I type these words in Atlanta, the Carolinas are being hit by a hurricane. As Vann Newkirk wrote for the Atlantic in August, “Climate change is not a future problem. Climate change is a current problem.” He pointed out:

Heat waves, droughts, storms, floods, and other extreme events have garnered increasing attention. The largest wildfire in California’s history is now raging almost a year after the previous record holder hit the state. Hurricanes Harvey and Irma ravaged the Gulf Coast and Florida in late August last year. Hurricane Maria became the second-most deadly natural disaster in contemporary American history when it passed over Puerto Rico last September. And the 13th anniversary of the Louisiana landfall of Hurricane Katrina, the largest such storm, is on August 29.

It’s not just the natural order we’ve upended. We’ve lost control over our own creations. Banks have learned nothing from 2008. A story from the Times four years ago noticed that financial institutions didn’t really care about fines. The title of the feature was the ominous “At Big Banks, a Lesson Not Learned:”

Are the colossal regulatory fines extracted from big banks today likely to deter their officials from violating the same rules tomorrow? Or are these billion-dollar settlements viewed simply as a cost of doing business, and not a very large one at that?

The answer, apparently, was “no.”

According to the case brought by Finra, a securities industry regulator that oversees all of the nation’s brokerage firms and their employees, 10 firms, including many of the same banks in the 2003 settlement, paid $43.5 million for violating the research rules. The violations took place during a 2010 competition to underwrite an initial public offering of Toys “R” Us; among the firms named by Finra were Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley. Although the Toys “R” Us stock offering was never completed, all of the firms enlisted their analysts’ help in trying to win the deal, according to Finra. It said the firms also promised favorable research coverage of the retailer.

This recidivism is happening while the next financial crisis is building. From a Times story published last week:

The global financial crisis is fading into history. But the roots of the next one might already be taking hold. The amount of American student debt — roughly $1.5 trillion — has more than doubled since the financial crisis. It is now the second-largest category of consumer debt outstanding, after mortgages. Public colleges and universities, hurt by state budget cuts, increased tuition. The drop in house values also made it harder for families to tap into their home equity to pay for tuition. As a result, the financial burden shifted to students, who took on heavier debt loads to pay for school.

Many borrowers are already falling behind.

Meanwhile, because of the world we have made, people flee their homelands. Immigrants make up the highest share of the American population since 1910:

The foreign-born population in the United States has reached its highest share since 1910, according to government data released Thursday, and the new arrivals are more likely to come from Asia and to have college degrees than those who arrived in past decades. … The last historic peak in immigration to the United States came at the end of the 19th century, when large numbers of Europeans fled poverty and violence in their home countries.

A fair number are from countries we (or our allies) have meddled in:

Dr. Fadel E. Nammour, a gastroenterologist in Fargo, N.D., who moved to the United States from Lebanon in 1996, said he has noticed more immigrant-owned restaurants since he moved to North Dakota in 2002. In recent years, the state has settled refugees from countries including Iraq, Somalia and Congo.

We’re used to thinking the finale was around the corner, in some ill-defined and far-flung future. But as Chapo pointed out, tomorrow is now.

To be clear, this is not the end of civilization. But it’s the endgame of society as we’ve known it. And this gives us a chance.

Here is why: most political effort is expended to change minds. And most of changing minds is about enticing people to share your assumptions—to make them accept what you already believe as gospel. It’s not always easy. Global warming truthers can’t accept that climate change is real. Evangelicals can’t accept that Trump is not their friend. Neoliberals can’t accept that late-stage capitalism is doomed. The elite and older generations can’t accept that the young have scant economic prospects.

M.H. Miller graduated in 2008. She wrote about it in a recent editorial:

The commencement speaker was Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. She described the “extraordinary moment in history” in which all of us were receiving our degrees, a vague allusion to the country’s struggles at the time, many of which have only become worse in the intervening years…

Mrs. Clinton then echoed a fantasy of boundless opportunity that had helped guide the country into economic collapse, deceiving many of the parents in attendance, including my own, into borrowing toward a future that they couldn’t work hard enough to afford. “There is no problem we face here in America or around the world that will not yield to human effort,” she said. “Our challenges are ones that summon the best of us, and we will make the world better tomorrow than it is today.” At the time, I wondered if this was accurate. I now know how wrong she was.

And even if you do convince people that economic and environmental catastrophe looms, there’s another fight ahead. Once they accept the truth, you must convince people your truth has urgency.

This is a difficult task. Americans are a future-obsessed people.

But then again, this is a story about beginnings.

I believe the present moment is of great hope. The in-your-face necessity of now commands bold action. When I think of the task before us, I remember the great American talent for doing the right thing at the very last minute, at the very crack of doom. As the diplomat Abba Ebban said, “Men and nations behave wisely when they have exhausted all other resources.”

How long did we put off the brutal question of chattel slavery? After a century of dithering, the levee broke. The Civil War came, and dealt its reckoning. But we acted – eventually. The Depression went on for a decade, poverty scoured America, and we acted – eventually. Fascism swallowed the world, and Russia and China and Britain fought on. Only then, when pushed, did we act—eventually.

And so it is now. The time of changes arrives. And with it, the possibility of transformation.

This is the “eventually” moment.

We are not lacking resources. During the time of whale oil, there was petroleum aplenty below the Earth, even if we had no use for it. I realize the irony of that example, but the point is clear. There is matter to be used; there are finely-machined tools ready at hand. They will be sufficient for whatever job is required.

We are not lacking money. In 2014, global world GDP was $78.28 trillion. America spent $1.5 trillion on the godforsaken F-35 jet, and $2.3 trillion on the Iraq War. In 2004, America and Europe cashed in a combined $31 Billion on ice cream. We’re the kind of country that can throw away treasure on a joke. There are king’s ransoms for whatever project we need to accomplish.

We are not lacking ideas. Every city and every school in this country is filled with brilliance and insight. Learned journals and new books teem with solutions for our present crisis. There are paths we can follow.

What is lacking is will. Simple will. We are chained to old ideas, moth-eaten truisms that died with the last century.

Centrists love to speak about “conversation.” Well, the conversations are over. We know that our prisons are unjust, that we have studied war too long, that we boil the seas, that we brutalize our citizens of color, and that we hoard for the rich. We know the results of that dialogue. All conversations eventually end, and the moment of action arrives. Everything’s eventual. Tomorrow is here. What will we do on the day after? Choose.