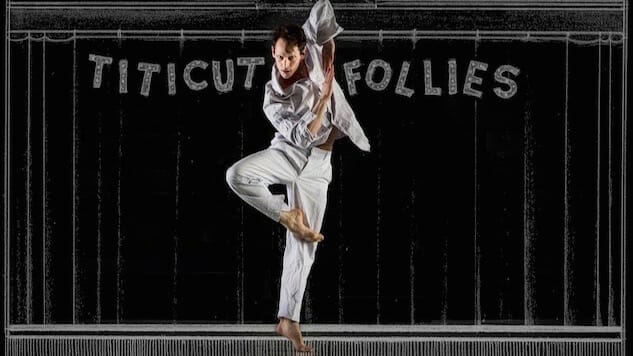

Filmmaker Frederick Wiseman is a master of fly-on-the-wall verité, known for his sprawling documentaries that resist any sense of manufactured drama or stylized structure. His first film, Titicut Follies (1967), captures life in the mental ward of a Massachusetts Prison and is framed around the inmates preparing to put on a musical revue. “I very interested in dance,” Wiseman said the other weekend during a talkback after the New York premiere of James Sewell’s ballet based on the film. “I got tired of seeing ballets about princesses who’d been asleep for 20 years. I thought the compulsions and behaviors of psychotic people might be translated into ballet.”

Wiseman, who made an epic portrait of the Paris Opera Ballet, La Danse (2009), and is an avid fan of the art form, approached choreographer James Sewell with the idea in 2014. “I have no idea how to make a ballet out of this, and I’ve done ballets on torture and euthanasia, so I said yes,” Sewell recalls.

During the creation process, there was never an attempt to copy the film frame-by-frame. “There was no effort to reproduce the movie. The idea is to take some of the ideas from the movie and see if they could be translated into ballet terms,” Wiseman explains. Sewell echoes the sentiment: “I wanted to capture the arch of the film. Every year they would do this musical revue in the asylum. It’s crazy.”

Because the film centers on preparing for this performance, seeing these characters in a ballet isn’t much of a stretch and adds an elegant form of expression for characters who are not only incarcerated but locked inside themselves. In one scene an inmate’s birthday is celebrated and volunteers aid the festivities, showing a stark contrast between the reality inside and out of the mental ward. “When the ladies come to volunteer for the birthday party, they bring color with them,” Sewell notes of the colorful dresses which make the gray uniform look even starker in comparison.

The jazz score by Saturday Night Live musical director Lenny Pickett adds another level of counterpoint. “The music is the straight man,” Pickett observes of his contribution. There are moments when the contrast between reality and insanity draw absurd and uneasy laughs. “Oftentimes we laugh at things we don’t understand and things that make us uncomfortable,” Sewell offers up as an explanation. “In the film, there are moments that are so uncomfortable you have to avert your eyes and scenes that are so absurd, you laugh but feel guilty.”

Wiseman, who has an acerbic sense of humor, provides a slightly different interpretation. “You don’t have to feel guilty; there are moments that are genuinely funny.” To find humor in another person, especially in dire situations, is to recognize their humanity. And if Wiseman’s films have an overarching theme, this would be it. He also delights in the oddities and perversions of society’s imperfections. “One of the prisoners there who couldn’t be photographed was the Boston Strangler,” he remembers. “He had a little business where he made chokers for women.”