Why the Survival Series Alone Is a Masterpiece of Human Psychology

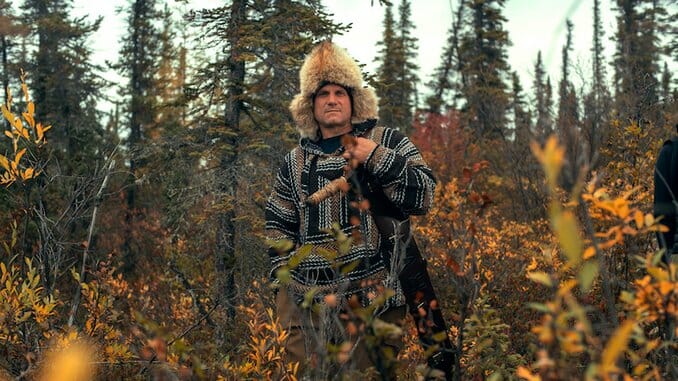

Photo Courtesy of History Channel TV Features Alone

(Editor’s Note: Mild spoilers for Alone Seasons 1 and 6 are below)

It’s interesting that the evolution of “survival” competitions on TV began with great complications—tribes, games, challenges, votes, etc.—and have progressed to the simple. If the History Channel show Alone (now on Netflix) represents the culmination of this process, it’s also the apex. The premise could not be more basic: Ten people are dropped in the wilderness with ten items of their choosing (no guns), they film themselves and have no human interaction beyond infrequent medical checks, and the winner is the last person to quit. But from those simple foundations, it rises far above its predecessors and allows a deeper and more penetrating insight into the brain of our strange, resilient species than anything Survivor or its knock-offs could manage in a thousand episodes.

In the early episodes, Alone is a study in contrasts. The first season was set on Vancouver Island, which holds a large population of black bears and wolves. Two of the contestants were men who spent their lives with guns. One was a police officer, the other was a rabid enthusiast who never left the house unarmed, and they both presented gruff exteriors. But when they found themselves alone in the wild, the test unmade them almost instantly. It’s easy to be sympathetic, since most of us watching from the comfort of our couches wouldn’t last an hour, but then again, most of us don’t claim to be survivalists. The police officer tapped out first, terrified of the bears. He made it 12 hours. The gun lover went next, having lasted just two days, because he was tormented by the howling of the wolves.

Then there was Mitch. Mitch came from Massachusetts, had dreadlocks, and looked, if anything, like a grunge-style hippy of the type that prevailed in the early ‘90s. On his first night, as he huddled in his rain-battered tent, he turned on his camera and stared at the bright light. There were bears, he said, and he could hear them walking on the path near his tent. But it was no problem: If they came in, he’d flick on his headlamp and jab them with his knife. He emphasized the point by thrusting the blade at the camera: bam, bam, bam.

Mitch lasted 43 days, showcasing endless ingenuity in finding food and water, and only left because he felt guilty that he wasn’t spending more time with his mother, who was dying of cancer.

Mitch was better at survival skills than the two gun-toting men who tapped out before him, there’s no doubt, but he had something equally as important. It’s hard to name, being a heady blend of willpower, toughness, and a capacity for suffering, but it’s the mental side of the game that distinguishes the true contenders from the quitters. To see Mitch hunker down, ready to fight his corner even against an intruding bear, was a study in variability when compared to the terror in the eyes of the others. You can learn to start a fire, to gather plants and berries, even to hunt and fish, but without a fundamental store of resilience, your brain will become overwhelmed before your body.

Of course, it’s not all psychological. In that first season, the contestants who lasted the longest showed incredible cleverness, and that’s half the fun. One contestant built a yurt and a canoe, which helped him gather shellfish on an adjoining island. Another caught mice with a Paiute deadfall trap. Mitch caught fish and invented a brilliant way to start a fire when he thought his ferro rod was eroding too quickly. The winner of that season made a native American fish trap from the trees in the forest, but actually had better luck crafting a similar device from a washed-up plastic bottle. In Season 6, which is the only season available on Netflix, the winner displayed such a range of survival ability that he almost seemed superhuman.

That skill element is fascinating, and generally makes the difference between the winners and those who come close but can’t quite prevail due to lack of food. But it’s the brains that make for the most compelling television. One thing you pick up quickly are the telltale signs that a player is cracking. They begin to make excuses, to bring up family in a way they hadn’t in the early days, and to talk more and more about the difficulty. They’re dwelling on it, and when that dwelling begins, the end is in sight. “I don’t want to quit,” they’ll say, but in some critical way, they already have. Several times in the two seasons I’ve watched, there’s been a precipitating accident or event that forces them to abandon the island, and I caught myself wondering if any of those were faked by the player to give himself an excuse. An ungenerous thought, maybe, but for those who last more than a few days and realize they can’t hack it for much longer, much of their mental energy is spent looking for excuses; for noble reasons to quit.

And others simply won’t. In Season 6, there are several competitors who couldn’t quite cut the mustard from a survival angle in the Canadian Arctic, and who ran out of food and struggled even to find water. They lost weight, turned into hollowed-out shells of themselves, and could barely muster the energy to melt snow and check empty rabbit snares as the temperatures dropped.

And yet, they simply wouldn’t leave. It took a medical crew to force them, and even then, they protested. One man, who had come close to being delusional at various points, refused to go and only relented when they told him he’d lost 80 pounds and was in grave danger of organ failure.

I believe he, and a few like him, would have starved to death or come close if they’d been allowed. What can you say about this kind of endurance, this strange spirit? It’s about more than the grand prize of $500,000 (recently raised to $1 million). It’s about a stubbornness that’s bone-deep, and disdain for the idea of quitting. It’s about embracing suffering as part of the condition of life. It makes you proud to be a human being, and that’s hard to come by in 2020.

The biggest compliment I can pay Alone is that although I’m fully aware that I’d humiliate myself if I ever tried it, I can’t help looking out my window this past week and wondering if I should buy a tent. The “connection to nature” concept might be a cliche, but there’s truth to it, and watching this show reminds me that there’s something I’m missing. There are thoughts and experiences I’m not having as I stare at my laptop screen. All the while, time is passing, and there are things about myself that I simply don’t know.

Season 7 of Alone airs Thursdays on the History Channel; one season is also available on Netflix.

Shane Ryan is a writer and editor. You can find more of his writing and podcasting at Apocalypse Sports, and follow him on Twitter here .

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.