Falling “So In Love” With Curtis Mayfield and Orchestral Manouevres In the Dark

10 years apart, Mayfield and OMD wrote two of the prettiest songs I’ve ever heard and titled them both the same.

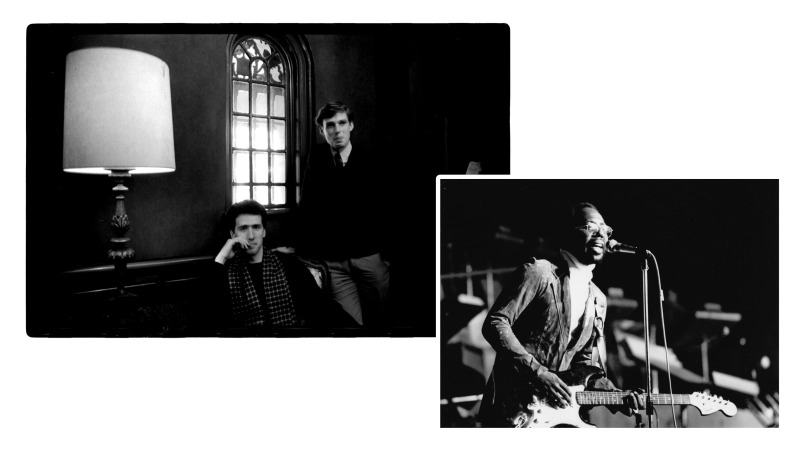

Photos by Lisa Haun/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images & Gilles Petard/Redferns

Apple Music is celebrating its 10th anniversary, my streaming app tells me. For the occasion, they’ve made a playlist of the 100 songs I’ve listened to the most in my decade-plus as a subscriber. Near the top are the usual suspects—two tracks from REO Speedwagon, “Stumblin’ In” (which I listened to 838 times in 2022 alone), and a smattering of music I heard first in a television show and have loved ever since, like Dion’s “Only You Know” (Ozark), the Vogues’ “You’re the One” (The Queen’s Gambit), Fleet Foxes’ “Montezuma” (Girls), and the Avett Brothers’ “No Hard Feelings” (Love). But just 10 spots apart are “So In Love” and “So In Love,” great but not top-billed tracks from Curtis Mayfield and Orchestral Manouevres In the Dark, respectively—one song I discovered cosmically, in the infancy of my Apple Music days, and one song I discovered accidentally, in the throes of an ever-evolving synth-pop obsession.

My biggest compulsion is repetition. I watch things over and over. I listen to things over and over. I eat the same food almost every day. But in that repetition is a gesture of comfortability, and I have a compendium of “sleep songs”—songs that I play to fall asleep and wake up hearing, including (but not limited to) Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Early Mornin’ Rain,” Cassandra Jenkins’ “Hard Drive,” and the Capris’ “There’s a Moon Out Tonight.” What I am trying to say is: I listen to a lot of music, and I listen to a lot of music a lot. And, if Apple Music is a reputable agent of accuracy, then it should be noted that, in the catalogued history of my musical habits from 2015 until now, I have only listened to 11 songs more than Curtis Mayfield’s “So In Love” and I have only listened to 20 songs more than OMD’s “So In Love.”

I found Mayfield’s “So In Love” in the same fashion as many other millennials and older zoomers: through Grand Theft Auto V, thanks to Frank Ocean’s in-game radio station, Blonded Radio. I grew up in the rural Midwest, far enough away from city civilization that no light pollution so much as crept into my skies. As a teenager, all I had were virtual nights under the banner of Los Santos, roving violently down freeways while the same hundred songs shuffled across a dozen channels. But there was a moment, during nightfall, where “So In Love” came on and shared its perfection with me. I used to play videogames because I had no one. GTA V, despite its faults, teleported me into necessary fantasy: I could drive and it didn’t matter how far; I could spend money and it didn’t matter how much.

And when I heard “So In Love” for the first time, Harold Dessent’s woodwinds, which color the atmosphere of There’s No Place Like America Today entirely, came rushing in under the cover of Lucky Scott’s vibrating bass and Rich Tufo’s keyboards. The title isn’t a misnomer; “So In Love” is for the romantics. I began waiting for the song, tuning into every in-game night and postponing missions for the sake of catching just a second of Mayfield’s high-heaven voice and sobbing organs. I could have just played the song on my cellphone, but there was no magic in that. I could never figure out the algorithm or predict its arrival, though; the song always found me, not the other way around. I learned soon enough that you can’t play Grand Theft Auto forever, but I certainly did try to and still do, as its successor gets hit with repeated delays. But eventually, my PlayStation 3 gave up, so I went to the Record Connection in nearby Niles, Ohio to buy a copy of There’s No Place Like America Today on vinyl. They didn’t have it, so I spent my college years lying in bed with an iPhone by my ear, sitting with the cooing warmth of “So In Love” until I could draw it from memory.

There’s No Place Like America Today was a bleak yet comforting dissection of post-Nixon America—a collection of songs expounding on love, sensuality, and survival’s existence under the thumb of systematic oppression. The tranquility of “So In Love” momentarily banishes the album’s fits of God and funk. “Life is strange,” Mayfield sings, his falsetto struggling. “Believe me, it is true: We don’t always mean the things we sometimes do. Look at me, look at you.” Dessent’s saxophone swells but never colossally, invoking a divide between splendor and sensibility. Quinton Joseph’s drumming putters on like a low-riding Oldsmobile crawling through traffic; he bats a cymbal and the air around him is touched into velvet. If “So In Love” is to suggest anything to its listeners, it is that to be alive is to be political—to be in love is to be political, and to love and to hope means you must be ready to sacrifice in the name of peace. “You do so many things with a smiling face,” Mayfield sings, pushing a psalm into the language of the living.

I would have never found out about Curtis Mayfield had it not been for Blonded Radio in a game I begged my parents to let me play. He wasn’t signed to Motown, and he wasn’t the leader of a hard-rock band, and he wasn’t a chart-topper during the Reagan years. Curtis and Super Fly weren’t on rotation in my household, except for when the latter’s title track showed up in episode five of Freaks and Geeks. By the time millions fell victim to the Stranger Things boom of ‘80s nostalgia in July 2016, I’d already been there for a decade—placed into the clutches of commodified retrospect lovingly by my mom, who graduated high school in 1988 and kept her car radio dial tuned to MIX 98.9, Youngstown’s “80s to Now” station.

DURING THE WEEK, hits of the aughts and 2010s would rummage into 98.9’s focus. But the station’s weekends were reserved for big hairdos and ostentatious materialism, for clashes of Prince and Madonna and one-hit wonders barely hanging on to FM relevancy. It bled into what reality waited for me outside of the car: Mom took me to a Def Leppard and Poison concert on the day Michael Jackson died; she taught me that George Michael and Rick Springfield were timeless heartthrobs; she loaded my blue iPod Shuffle with songs by Bon Jovi and Duran Duran, bands I learned about on hour-long VH1 specials and remembered the names and motions of. And, though every year came with gifts in tribute to my evolving childhood taste, perhaps none were as definitive as the Pure 80s CD she bought for me in 2004 or 2005. I wore the disc out until it was too scratched to spin.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-