Time Capsule: Curtis Mayfield, There’s No Place Like America Today

Subscriber Exclusive

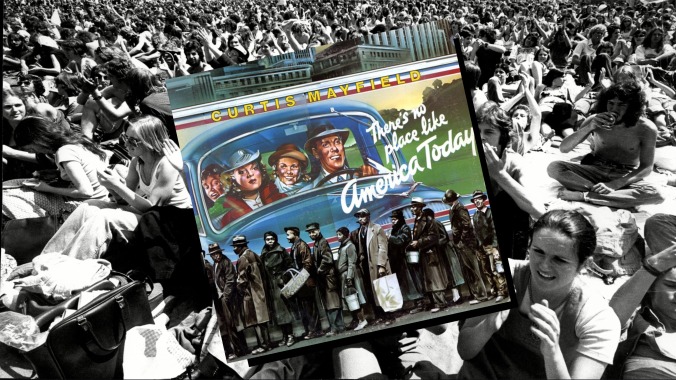

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Curtis Mayfield’s deeply profound and splendidly subdued 1975 masterpiece, a bleak yet comforting dissection of post-Nixon America that dares to expound on what love and survival can exist under the thumb of a system rigged against you.

I’d gone without a gaming system of any kind since the early 2010s, when I had a PlayStation 3 that inevitably capsized beneath my growing teenage intrigues. I was far more interested in music and in dating and in all the things I believed high schoolers were supposed to be into. When my controller finally broke, I never got it replaced and instead retired the console altogether. I remember then, in 2013, the release of Grand Theft Auto V being something of a cultural phenomenon. Friends skipped school to play the game on release day; it was all I heard about for weeks. Even as the years passed and 2014 became 2015 and then graduation came in 2016, it was still ever-present in the pantheon of my generation’s zeitgeist. By the time I downloaded Fortnite onto my college-issued iPad in 2018, it felt like the gaming world had long passed me by.

So when, just three days after Ohio went into COVID-19 lockdown, my birthday came around and my parents thought it made sense to give me a PlayStation 4, a gift that would no doubt be a welcome distraction when there was nothing else good to do. The console had been out, by that time, for nearly seven years in the United States. Just as the gaming world had already left me behind, the PlayStation 4 would, come election time in November, become immediately outdated upon the release of the PlayStation 5. Nevertheless, I saw it fit to buy GTA V before anything else—I needed to catch up on the world I had remained in such close proximity to all those years ago.

I’ve become increasingly sentimental about everything over the last four years. I’m the type of person who, when a particularly vibey song comes on the radio in GTA V, I put all of my focus onto savoring that moment. When Bob Seger’s “Night Moves” engulfs the Los Santos Rock Radio station, I love to saunter around the hills and find a good parking lot to linger in. The same goes for Queen’s “Radio Ga Ga” and the Highwaymen’s “Highwayman.” Even when Naked Eyes’ “Promises, Promises” stumbles out of the tape-deck, I am hopelessly romantic about it. The game’s crime-fueled undercurrents and storylines fall away into a portal of faraway bliss.

But it was Frank Ocean’s in-game version of his Blonded Radio where it all went different. Cruising down the game’s version of the Pacific Coast Highway, a song called “So in Love” by Curtis Mayfield trickled through the speakers of my television. It was a crisp, cloudless coastal night and, in a flash, its volume got cranked up. Hundreds of hours of logged gameplay later and I still find myself pausing missions or rerouting the GPS when “So in Love” comes on, if only to let myself sit with Mayfield’s voice and those galloping horns. When the world had closed in on itself four years ago, it was a window into a kind of living I didn’t quite have access to. Now, even as the world has opened back up again and I, from time to time, log into GTA V and make pilgrimages across the San Andreas map, I let time slow down when “So in Love” comes on the radio. I let it all feel as real as it ever could.

Prior to GTA V, I of course knew as much about Curtis Mayfield as anyone might have. I was familiar with Curtis and Super Fly, two of his first three albums which also happen to be two of the greatest albums of the 1970s and two of the greatest albums period. Super Fly the movie, along with Car Wash, practically won Academy Awards in my house when I was growing up. I could recognize “Move On Up,” from Mayfield’s debut, with ease, as that opening horn ensemble is progressive and psychedelic. Mayfield existed in the same thought as Al Green, Isaac Hayes and Donny Hathaway had—Black singers who existed adjascently to Motown but were no doubt just as fundamental in shaping the foundations of contemporary funk and pop-soul. Mayfield had first gained attention a decade earlier as a member of the Impressions, a trio of singers who dabbled in everything from gospel to doo-wop by the time Curtis left in 1970 to pursue his solo career.

After Super Fly spent four weeks atop the pop albums chart in 1972 and spawned two hit singles (“Freddie’s Dead,” “Superfly”), Mayfield would make Back to the World, collaborate with Gladys Knight & the Pips on Claudine and then, within about 18 months of each other, release Sweet Exorcist and Got to Find a Way back-to-back and compose the soundtrack for Let’s Do It Again with the Staple Singers. By the time he got around to putting out There’s No Place Like America Today in May 1975, he’d put out seven LPs in less than five years. So often, when considering what the best run of albums by one artist in music history was, our minds rightfully go directly to Stevie Wonder’s streak from Music of My Mind through Hotter Than July. But, Mayfield’s discography from 1970 through 1975 was very, very good as well. Curtis, Super Fly and There’s No Place Like America Today would solidify that alone, but those other aforementioned albums are all close to top-drawer, too.

There’s No Place Like America Today is sorely underrated especially. It only peaked at #120 on the Billboard 200 and didn’t even crack the Top 10 on the R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart upon release. Mayfield’s career was never all that defined by accolades anyway. Before his death in 1999, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice (once as a member of the Impressions in 1991 and again as a solo artist in 1999) and nominated for eight Grammys, losing all of them. In 1994 he was given the Grammy Legend Award and then, a year later, was bestowed with a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-