Stonewall

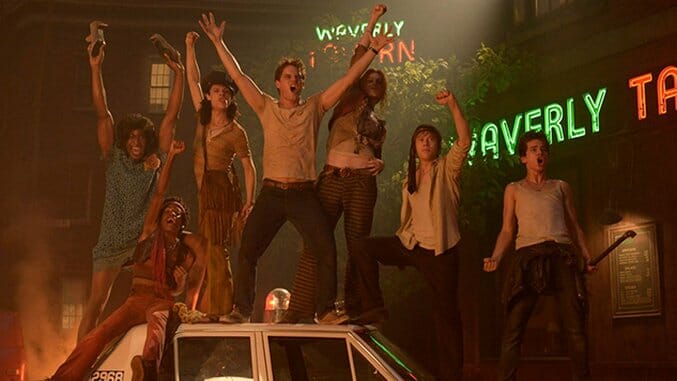

If you crack a history book to brush up on the Stonewall riots, you might stumble across the names of gay and transgender activists Sylvia Rivera, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy and Marsha P. Johnson. If, once you’ve finished your fact checking, you decide to take a peek at the cast list for Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall, an ostensible biopic about that landmark 1969 gay rights demonstration, you’ll find that Rivera and Griffin-Gracy don’t even show up as footnotes. If, after all of that, you still decide to corrode your soul by watching the movie, you’ll notice that Johnson (Otoja Abit) shows up as barely a bit character in the depiction of her own struggle, led, in Emmerich’s vision, by a clean-cut well-to-do white boy.

By the time Emmerich gets to the riots, which takes about 100 minutes of the film’s 120-minute running time, you’ll want to chuck a cinder block at the screen. Describing Stonewall as merely a crummy biopic would be like describing Pasolini’s Salo as a rom-com. For this film, “crummy” would be an improvement: What Emmerich has done is unwittingly flip the bird at the foundation of the modern gay rights movement. Before the movie even opened, the streets of social media were already mobbed with indictments of his efforts, and, like any fire worth its accelerant, all he’s managed to do by coming to his picture’s defense is hasten the blaze. His reply to critical response is appalling, but it illustrates the foundation of misunderstanding he’s built Stonewall upon.

There are two stories at play here. The first is about late 1960s political and social attitudes, marked by the consequences of the era’s panicked homophobia. The second story takes a ground-level perspective on those attitudes, as young Danny Winters (Jeremy Irvine) is outed among his Indiana high school classmates and subsequently disowned by his football coach father (David Cubitt, who helpfully wears a cap that reads “coach” in case we forget his occupation). So far, so heartbreaking, but the film mashes its intertwining plots together less elegantly than Victor Frankenstein stitches together corpses. (Incidentally, that allusion also aptly describes the film’s torpid visual scheme.)

Emmerich wants Danny to be our “in” to the events that lead to the Stonewall riots. This, on the page, is a harmless, tried-and-true storytelling device: Insert audience identification character into a setting and anchor our perspective to him or her. But Danny is a big, hunky slab of bland engineered to make white moviegoing audiences feel less threatened or alienated by the culture Stonewall portrays. We never really get a sense of him as a character, even when he’s making overwrought outbursts about whatever circumstance over which Emmerich and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz demand he lose his temper. Danny reacts to conflict as the movie requires him to. Danny isn’t a character—he’s clip art. One second he’s not sure where he fits into the battle for gay rights. The next, he’s stirring up mob violence with his pal Cong’s (Vladimir Alexis) trusty brick.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-