7 Influential Screenplays by Shinobu Hashimoto

Shinobu Hashimoto, one of the most revered screenwriters in Japanese film history, passed away last July after making it to 100 years old. Known for writing jidaigeki films (period stories often about samurai or ronin), especially collaborating with Akira Kurosawa, his 60+ credited works were as versatile as they were unique within their genres, from terrific dramas like Ikiru and I Live in Fear, to crime mysteries like The Bad Sleep Well. His streak with Kurosawa ended with the box-office bomb Dodeskaden (1970), yet he worked with a variety of formidable auteurs and was prolific through the late ’80s. He even directed three features, his drama about post-World War II relations between Japan and the U.S., 1959’s I Want to Be a Shellfish, the highlight.

To get a sense for just how deeply Hashimoto influenced the art of screenwriting, let’s dive into some of his best-known works.

Some spoilers follow.

Rashomon (1950)

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Hashimoto’s first credit revolutionized the traditional single protagonist perspective. Rashomon pinpointed a simple but important fact: If these stories are made from the memories of characters—memory is fallible, and people are prone to lies and exaggerations—why not give each perspective its due, telling the tale of a married couple ambushed by a rowdy criminal (Toshiro Mifune) through each person’s memory, aggrandizing the positive aspects of whoever’s telling the story while villainizing those of the other two, until objective truth is impossible to grasp, but humanism and naturalism thrives.

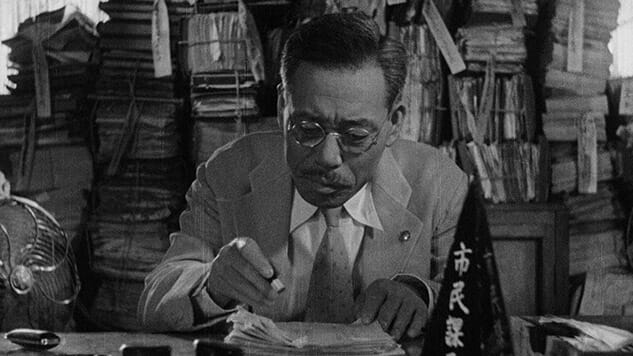

Ikiru (1952)

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Kurosawa’s intimate treatise on taking full advantage of our lives in order to leave this world a better place than the state in which we entered it, Ikiru is a rare screenplay that unrolls in four acts. Takashi Shimura’s lowly bureaucrat finds out he has terminal cancer, tries to find meaning through hedonism and, when that doesn’t work, attempts to live vicariously through a lively young girl. The fourth and final act switches perspectives from the film’s firth three: With the bureaucrat now dead, we see his friends and family deconstruct the motivations behind his surprisingly altruistic actions mere months before his demise. This change in point of view emphasizes the ultimate moral point of this beautiful tale, that what we do is perhaps more important than who we are.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-