Why Aren’t You Reading Sean Lewis & Benjamin Mackey’s Saints?

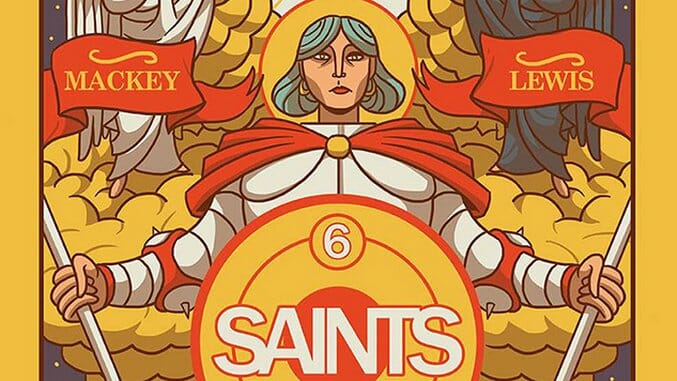

Saints Art by Benjamin Mackey

When we first recommended Sean Lewis and Benjamin Mackey’s Saints, we called the Image sleeper an “an enticing mix of Preacher and WicDiv,” a comparison we feel comfortable reiterating now that the book is more than halfway through its run (solicited as an ongoing, the book has been re-positioned as a nine-issue maxi-series). Lewis, a playwright, and Mackey, who originated the concept, are working in the same Christianity-inspired slum-Americana wheelhouse as Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon’s Vertigo classic, and the pitch of martyrs returning in the bodies of contemporary young people bears more than a passing resemblance to Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s reincarnated pantheons. Saints’ protagonists are no rock stars, though: the closest example is main character Blaise Ramirez, the 31-year-old non-starter groupie to a noxious death-metal band. Blaise’s saintly skill lets him “lay hands” on the lead singer’s scream-addled throat to repair shredded vocal chords.

Blaise’s power is very specific, but his fellow saints find themselves blessed/cursed with more widely applicable abilities: flamboyant self-harmer Sebastian is an archer with angel-kissed aim; Lucy, raised by fundamentalists who readily accept and celebrate her sainthood, can show you your past and future; and latest recruit Stephen can telekinetically hurl boulders. The saints of Saints aren’t just Christian reincarnations, they’re practically superheroes. The fifth issue even had a back-up featuring “Sebastian’s original team”—more famous saints with more useful powers.

Described by publisher Image as a “horror/crime” book, Saints instead hits a similar beat as Black Mask breakout We Can Never Go Home: what if mutants who badly needed a Charles Xavier figure suddenly appeared in a world with no School for Gifted Youngsters? Instead of fleeing into the arms of a trusted mentor, the saints find themselves following the advice of a talking Jesus portrait and holing up in the house of a genuinely satanic black metal bro, where they pick up a demon dog. That’s not the kind of guidance doomed youth need in a godforsaken world.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-