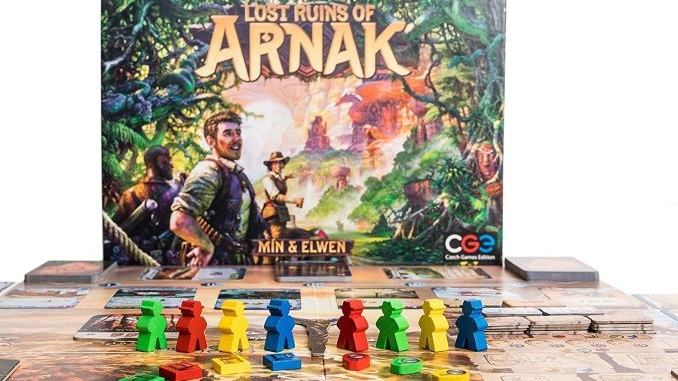

Lost Ruins of Arnak is a late 2020 release, a bit older than what I typically review here, but it’s become such a breakout hit—and a surprising one, given its size and the daunting setup—that it’s worth reaching back a little to give it a full breakdown. The game was one of the three finalists for the 2021 Kennerspiel des Jahres (experts’ game of the year), losing out to Paleo, but has raced into the top 40 on the tough-to-crack BoardGameGeek all-time rankings, and is the #2 “family” game behind only the runaway hit Wingspan. It has quite a bit in common with that last title, as it’s more complex than the typical family-level game—put a pin in that for the moment—but is much easier to play once you get through the first round and understand the basic mechanics, with a very satisfying set of rules that can make the game fun even for players who don’t end up winning.

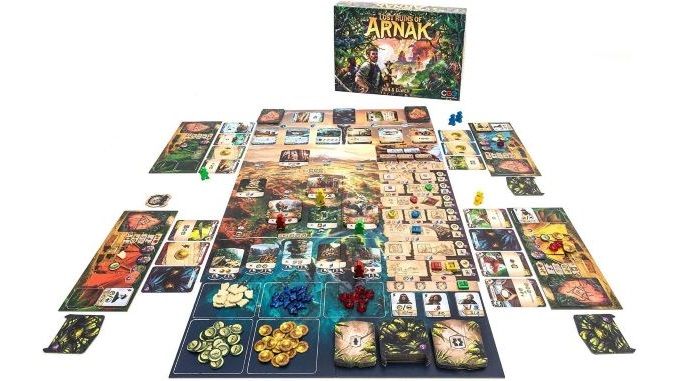

Arnak is an adventuring game that brings in a bunch of familiar game mechanics, including worker placement, deckbuilding, hand management, and track advancement, without giving you too much of anything. (As far as I can tell, the game’s title isn’t a play on arnaque, the French word for a scam.) Each player has two explorers whom they’ll place on the board at various dig sites, exploring the lost ruins of the title and gaining resources. They also start with six-card decks with four basic action cards that either let the player take one specific resource or allow placement of an explorer, and two Fear cards that are worth -1 victory point but can be used for explorer placement at the bottom dig sites. Players can also move their two tokens up the research track for more rewards, buy item or artifact cards to beef up their decks, defeat Guardians who appear whenever a new site is excavated, and more.

The game takes place over five rounds, and within each round, players may continue taking actions as long as they’d like, until they run out of possible moves. This often means exhausting everything in their hand of five cards, placing both explorers, and spending most or all of the resources they’ve acquired to either buy cards or move up the research tracks. One of the particularly clever aspects of the game is how often players get “free” actions—ones that don’t count against the one-action-per-turn limit—as they progress through the rounds. In round one, you won’t have that many opportunities to take a free action, but by round five, your hand will probably grant you many free actions, as will the assistants and other tokens on your personal board.

One common mechanic I see in many complex board games is track advancement, where players have to push their tokens up two, three, or even four tracks that might represent things like science or research or culture, but that are physically and thematically disconnected from the rest of the game. Tzolk’in, a heavy game I like, does this, as does Coimbra, a heavy game I think is overdesigned. Lost Ruins of Arnak simplifies this mechanic while also making it more central to the game; there is one track that sometimes offers two different paths, and there is always a reward for moving up. It’s the only way to gain Assistants, most of which give you one free action per round. It’s also a core source of points for the end of the game. You can’t ignore it, but you also don’t feel like you’ve wasted a turn or resources whenever you use it. And since moving up on that track doesn’t require the use of a card or a meeple, it doesn’t get in the way of the other things you’re trying to do.

There’s also a light deckbuilding aspect to the game that I’ve seen before-Taverns of Tiefenthal comes to mind—but that also works very well here. You start with the six-card deck, shuffling and drawing a five-card hand. If you buy an item card, it goes to the bottom of your deck, and gets to your hand in the next round or the one after. If you buy an artifact card, you play it immediately, and then shuffle it into your discards to go under your deck. All item and artifact cards are worth at least one victory point at game end, and all have useful powers on them, some of which are free actions and some regular, as well as movement icons for your explorers. There are also various cards and spaces on the board that allow you to “exile” (trash) a card from your hand or play area, which lets you get rid of Fear cards or even the starter cards that are less powerful and keep you from getting the better cards you’ve purchased into your hand more frequently.

The mechanics themselves are not that complex, but there’s a bit of a high cognitive load for a “family” game—and I do not agree with how Boardgamegeek defines that term. You’re asking a lot of a kid under 10 to keep all of the possible moves and the sequence of actions they might want to execute over multiple turns in their heads while they wait for other players to go. Wingspan is similar, one of the best games I’ve ever played, but one that asks a bit more of players than what I’d consider a family game. It’s a stepping stone, one level up from a family game, but not a complex one—a good game to play with your kids if they’ve gotten the hang of Ticket to Ride and Carcassonne and the like, and want something with a little more meat to it. Games take about a half hour per player, with a solo mode and adjustments if you play with fewer than four players, although setup can take a good 10 minutes on top of that. It’s worth the hype and praise, even if it’s probably a harder game than its advocates say.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.