10 Meta Films: When The Movie Knows You’re Watching

In my final year of college, I took a class called “CINEMETA,” a hybrid of film and philosophy that treated movies like living thought experiments. The syllabus was deeply curated and delightfully strange. Each week, we explored films that were aware of their own existence, asking one surprisingly slippery question: What actually makes a film meta?

These days it’s a word we use casually, whenever a movie winks at the audience or acknowledges it’s a movie, but “meta” isn’t just about clever self-reference. It’s about a kind of consciousness built into the film itself. It’s something you often feel before you can name it. A meta film knows what it is, and it wants you to know that it knows.

At its simplest, a meta film is self-aware, it reflects on its own construction, on the nature of storytelling, or on the relationship between audience and creator. Meta doesn’t always mean ironic or detached. Often, it’s a work that’s thinking about itself in real time. Some of the most common meta techniques include:

Self-reference: films about filmmaking or stories that comment on their own structure.

Breaking the fourth wall: characters who talk to us directly, blurring the boundary between fiction and reality.

Narrative recursion: stories that fold into themselves, becoming stories about storytelling.

Existential reflection: when a movie uses its own artifice to ask questions about perception, identity, or the act of creation itself.

Below is a short syllabus of films that embody different shades of meta-awareness, ranging from playful to profound, from Hollywood satire to art-house hallucination. Together, they make up a kind of mirror maze of cinema looking at itself.

1. 8½

Year: 1963

Director: Federico Fellini

Stars: Marcello Mastroianni, Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimée, Sandra Milo, Barbara Steel, Rossella Falk

Rating: NR

Federico Fellini’s 8½ might be the purest example of metacinema, a film that not only knows it’s a film, but knows it is becoming one in front of you. The story follows Guido Anselmi, a director suffering from creative paralysis while trying to make a movie, and the irony is that the film he’s failing to make slowly becomes the one we’re watching. Fellini folds the act of creation into the narrative itself, turning artistic crisis into content, and self-doubt into structure.

Formally, 8½ is a kaleidoscope of meta devices: dream sequences that bleed into reality, memories staged like film sets, and actors who seem to drift between playing characters and playing themselves. Even the title is meta, a nod to Fellini’s own filmography, his “eight and a half” films completed up to that point. In its final moments, when Guido accepts his failure and joins his cast and crew in a surreal circus of reconciliation, Fellini suggests that art and life are one continuous improvisation. The film ends where it began, with the artist both trapped and liberated by his own imagination.

2. Being John Malkovich

Year: 1963

Director: Spike Jonze

Stars: John Cusack, Cameron Diaz, Catherine Keener, John Malkovich, Orson Bean, Mary Kay Place

Rating: R

Few films literalize the experience of watching a movie quite like Being John Malkovich. Its conceit, a secret portal that allows ordinary people to enter a celebrity’s consciousness for 15 minutes, turns the act of viewing itself into the plot. It’s as if Jonze and Kaufman took the unspoken contract between audience and screen (“we live inside someone else for a while”) and built an entire surrealist fable around it.

The meta-techniques here are manifold. First, there’s embodiment as spectatorship, the characters become both audience and actor, inhabiting a performance while still aware of its artificiality. Second, there’s recursion, as the film keeps folding back on itself until John Malkovich literally enters his own portal, trapped in an echo chamber of his own image. When dozens of Malkoviches chant “Malkovich, Malkovich,” language collapses into self-reference, a meta loop so complete it becomes nonsense. Third, there’s authorship itself: the puppeteer Craig believes he’s finally in control of someone else’s narrative, but the movie reveals that the “self” is a performance written by circumstance and desire.

Visually, Jonze stages the portal sequences like film projection: The tunnel is the camera lens, the viewer slides through and loses their body, and what’s on the other side is pure illusion. Being John Malkovich becomes a critique and celebration of cinema’s voyeuristic power, its ability to let us live inside another person’s skin while reminding us that it isn’t ours to keep. It’s meta in form, structure, and spirit, a movie that opens the skull of stardom and lets us crawl right in.

3. The Player

Year: 1992

Director: Robert Altman

Stars: Tim Robbins, Greta Scacchi, Fred Ward, Whoopi Goldberg, Peter Gallagher, Brion James, Sydney Pollack, Lyle Lovett

Rating: R

Robert Altman’s The Player is a classic about filmmaking that weaponizes the machinery of the studio system against itself. It begins as a thriller–Griffin Mill, a slick studio executive, kills a disgruntled screenwriter, then tries to cover up the crime, but the brilliance lies in how Altman frames that story through the very conventions his film critiques. As the camera glides through endless meetings, screenings, and “pitch sessions,” the movie becomes a satire of storytelling itself, a film about people selling films about people selling films.

Altman’s meta-techniques are sly but relentless. The film is filled with Hollywood cameos (Cher, John Cusack, Julia Roberts, Bruce Willis) that blur the line between reality and fiction; they’re not characters, they’re industry ghosts haunting the frame. Altman also plays with genre recursion, his murder mystery obeying noir tropes only to expose how formulaic and morally hollow those tropes have become.

By the end, Griffin gets away with murder and lands the movie deal of his dreams, an ending so cynical it feels prophetic. The Player is cinema looking into its reflection and flinching.

4. David Holzman’s Diary

Year: 1967

Director: Jim McBride

Stars: L.M. Kit Carson, Eileen Dietz, Louise Levine, Fern McBride

Rating: NR

Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary is one of the earliest and eeriest examples of cinematic self-awareness. Framed as the confessional diary of a young filmmaker armed with a 16 mm camera, it masquerades as documentary realism while actually dismantling it. David, convinced that filming his life will help him understand it, turns the camera on himself, his girlfriend, his city, his every passing thought, but the moment he starts documenting, he loses what he’s trying to capture.

McBride deploys a web of meta-techniques that make the film feel uncannily modern. The faux-documentary form anticipates both vlogging and “mockumentary” decades before either existed. Direct address, David talking straight into the lens, creates intimacy, but also exposes performance, as every confession becomes a scene. By the time David is alone, abandoned, still filming himself, David Holzman’s Diary has transformed into a parable about the camera’s corrosive power, the way documentation distorts truth and turns experience into artifact. It’s a a meta-documentary before the term existed, and a prophetic glimpse of our own digital age, where self-portraiture and self-deception are now indistinguishable.

5. Adaptation

Year: 2002

Director: Spike Jonze, Charlie Kaufman

Stars: Nicolas Cage, Meryl Streep, Chris Cooper, Tilda Swinton, Brian Cox, Maggie Gyllenhaal, Ron Livingston

Rating: R

You simply can’t talk about metacinema without talking about Adaptation. Spike Jonze and Charlie Kaufman’s Adaptation is a meta-miracle of modern screenwriting. It is literally a film that adapts itself, questions itself, and then explodes into the absurd. The premise is simple: Kaufman, paralyzed by writer’s block while adapting Susan Orlean’s The Orchid Thief, writes himself into the script. The film that results is a dramatization of its own creation, collapsing the boundary between fiction and process, story and structure.

The movie’s meta-techniques are dazzling and infinite. Via self-insertion, Kaufman becomes both author and protagonist, splitting himself into twin brothers, Charlie and Donald, to literalize the war between art and commerce. Via structural recursion, every failed attempt at writing the screenplay is folded back into the screenplay itself, where the act of writing becomes the narrative engine. Intertextuality runs rampant, as Orlean’s nonfiction prose, Kaufman’s neurosis, and Hollywood storytelling conventions all collide in a single framework.

By the third act, the film mutates from a comedy into thriller, which is similar to The Player’s playing with genre, a deliberate sellout to the tropes Charlie despises, mocking Hollywood formula while obeying it, parodying narrative closure while delivering one. In this way, Adaptation becomes a film about artistic survival, how stories adapt to stay alive, how creators cannibalize their own insecurities for art. It’s a film devouring itself and somehow emerging so self-aware it leaves us with the exhilarating question of who, exactly, is telling this story anymore.

6. The Cabin in the Woods

Year: 2012

Director: Drew Goddard

Stars: Kristen Connolly, Chris Hemsworth, Anna Hutchison, Fran Kranz, Jesse Williams

Rating: R

Drew Goddard’s The Cabin in the Woods is a classic horror film turned inward, interested in the anatomy of horror itself. The setup feels aggressively and intentionally familiar: A group of college friends head to a remote cabin for a weekend of partying, only to find themselves stalked and slaughtered. But almost immediately, the film splits into two distinct layers of narrative. Above ground, chaos, below it, control. In an underground bunker, a team of technicians monitors the teens’ every move, adjusting variables and releasing monsters like lab rats in a psychological experiment. It’s a film about the system behind scare and the ritualized structures that manufacture terror as entertainment. The control room is a metaphor for the audience, for the invisible spectators who require the ritual to continue. We want the blood, we expect the tropes, the world keeps spinning only if the show goes on.

The film ends on an interesting nihilistic note. When the two surviving characters refuse to play their assigned roles, they doom the planet rather than submit to the system. It’s a moment of radical self-awareness, horror breaking its own fourth wall and choosing self-destruction (and maybe eventual rebirth) over repetition. In that sense, The Cabin in the Woods becomes the ultimate meta-horror gesture, a film that recognizes the futility of its own genre cycle and decides to burn the set down.

7. Mulholland Drive

Year: 2001

Director: David Lynch

Stars: Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, Justin Theroux, Ann Miller, Robert Forster

Rating: R

David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive is metacinema as fever dream, a film that dissects the corruption of Hollywood through the logic of nightmares. What begins as a glamorous neo-noir about a wide-eyed ingénue arriving in Los Angeles unfurls into something stranger and darker. Lynch blurs dream and reality, performance and persona, until the two are indistinguishable.

The film’s meta-techniques are subtle but profound. Through narrative recursion, the story folds back on itself halfway through, replaying characters under new identities, as if the reel has been spliced and rewound by the subconscious. Via structural dislocation, Lynch manipulates the editing rhythm, time, and sound design to make the audience feel as lost as the characters, aware that the film is constructing and deconstructing its own dream. Performance as illusion is another thread: The audition scene, where a terrified newcomer transforms into a sultry professional mid-take, reveals acting as transcendence and possession, the moment when fiction becomes more real than life. Mulholland Drive melts the fourth wall and captures a larger than life story about the industry and identity.

8. Birdman

Year: 2014

Director: Alejandro G. Iñárritu

Stars: Michael Keaton, Emma Stone, Edward Norton, Naomi Watts, Zach Galifianakis

Rating: R

Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Birdman is a meta-high-wire act, a film that performs its own anxiety about performance. Michael Keaton’s Riggan Thomson, a faded superhero star trying to reclaim artistic legitimacy by staging a Raymond Carver adaptation on Broadway, exists in a constant state of split identity. The film mirrors his psyche through its construction: a nearly continuous take that turns backstage corridors into the inner loops of the actor’s mind.

Its meta devices are everywhere. The illusion of a single shot is itself commentary, a technical bravura that exposes the artifice of continuity. The camera glides through walls and time, as if we’re inside Riggan’s unraveling consciousness, watching his ego and self-image collide in real time. Keaton’s own history as Batman hovers over every frame, blurring actor and character, reality and role. Theatre and film merge, each scene within the play becomes indistinguishable from Riggan’s breakdown, suggesting that the stage is simply another lens, another frame within the frame.

Birdman is metacinema through motion, with its restless camera and jazz score keeping the illusion alive even as it exposes its seams. The film asks, can art ever be pure when it’s built on vanity, nostalgia, and the need to be seen? In its final moments, Riggan leaps from the window, escaping his frame, or maybe just imagining that he does.

9. Synecdoche, New York

Year: 2008

Director: Charlie Kaufman

Stars: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Samantha Morton, Catherine Keener, Michelle Williams

Rating: R

Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York may be the least meta film to end all meta films, a recursive cathedral of mirrors where art, life, and mortality collapse into one another. The story follows Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a theatre director who receives a grant to stage a production “as big as life itself.” His response is to build a life-size replica of New York inside a warehouse, casting actors to play himself and everyone he knows. As the years pass, the play never ends, the lines blur, and the performance becomes indistinguishable from the life it’s meant to represent.

The film’s meta techniques are vast and existential. Self-reflexive storytelling structures every scene, as Caden’s project is a metaphor for Kaufman’s own creative paralysis, a work about the impossibility of finishing a work. Recursive performance, actors playing actors who play actors, turns identity into an infinite regression. Via spatial recursion, a replica of a city inside a city, a stage inside a stage, creates an image of cinema as a nesting doll of perception. Even time behaves metatextually, with decades passing in moments, years compressing into cuts, mirroring the editing rhythms of film itself.

By its final act, Synecdoche, New York becomes a film about life imitating its own representation. Caden’s massive set turns into a mausoleum of meaning, a monument to the futility of trying to capture reality. Kaufman transforms the meta form into something tragic and cosmic: the artist consumed by his attempt to understand existence.

10. The Truman Show

Year: 1998

Director: Peter Weir

Stars: Jim Carrey, Ed Harris, Laura Linney, Noah Emmerich, Natascha McElhone, Holland Taylor, Paul Giamatti

Rating: PG

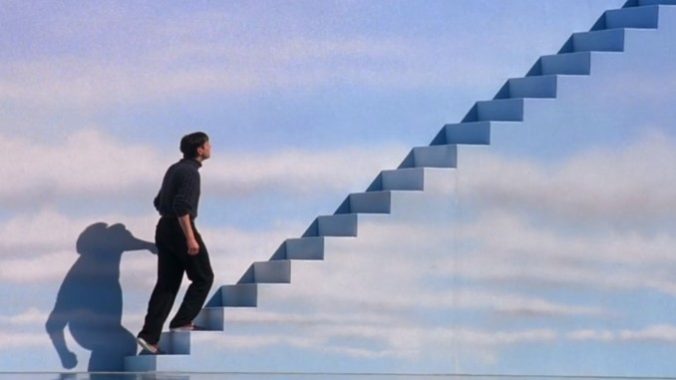

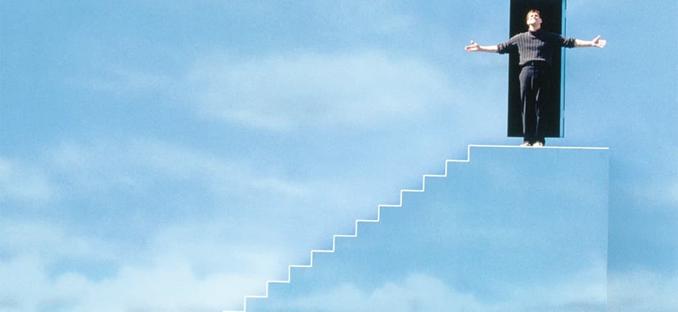

Peter Weir’s The Truman Show is perhaps the most accessible example of metacinema ever made. On its surface, it’s a whimsical satire: Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey), an ordinary man, slowly discovers that his entire life has been broadcast as a 24-hour reality TV show. But beneath the pastel-perfect suburbia and perpetual sunshine lies a film obsessed with authorship, spectatorship, and the ethics of creation. It’s less about a single man’s awakening and more about cinema itself realizing it’s been playing god.

The film’s meta-techniques are woven seamlessly into its fabric. World-building as production design: Truman’s hometown of Seahaven is a colossal film set disguised as small-town America, complete with invisible cameras hidden in every mirror, car radio, and buttonhole. Every visual frame is a frame within a frame, reminding us that Truman’s reality is engineered for our gaze. Direct address emerges through the in-universe television broadcasts and product placements, as characters unwittingly perform for an audience Truman doesn’t know exists. Weir turns the act of surveillance into cinematic grammar: Each shot feels voyeuristic, both comforting and cruel.

Even Christof, the show’s omnipotent creator (played by Ed Harris), is a stand-in for the filmmaker, a godlike director who confuses control for love. The climactic confrontation between Truman and Christof, broadcast live to millions, doubles as an allegory for the artist confronting his own creation. Truman says goodbye and walks off the set into the unknown, a moment that feels like a man breaking through the screen itself.

The Truman Show remains haunting because it implicates us, the audience, in its structure. We are the unseen spectators who keep watching, the ratings that keep Truman imprisoned. Long before social media, it predicted a world where every life is content, every act performed for invisible eyes.

The Meta Loop

Meta films remind us that storytelling is a loop, with every story, in some way, aware of itself. They break the illusion not to mock it, but to play with it, to stretch it, to see what happens when the moving parts of cinema becomes part of the narrative. They invite the audience to share in the act of creation, to feel the director’s hand still moving behind the curtain. Not everyone loves these films. Sometimes, I find them exhausting. Their circular logic can feel like a trap, the discourse around them echoing their own structure, analysis folding into interpretation folding into more analysis. In that Cinemeta class, talking about meta films often felt like living inside one.

Still, they hold a strange magnetism, especially for younger audiences. Maybe that’s because they mirror the way we already experience the world. Gen Z has grown up in an era of constant reflection, our lives lived through lenses, profiles, and screens. We are both performer and spectator, both protagonist and audience. Of course we’re drawn to movies that do the same thing, films that know they’re being watched and engage in the performance of self-awareness as naturally as breathing.

For us, the wink to the camera is a gesture of honesty, an acknowledgment of how mediated everything has become. These films are mirrors, but they’re also portals. They let us see ourselves seeing, feel ourselves feeling, and realize that the act of watching is itself a kind of authorship. The loop never really ends.

Audrey Weisburd is an arts and culture writer from Austin, Texas, currently living in Brooklyn. She also writes short fiction and poetry. She shares her work on Instagram @audrey.valentine.