Every Darren Aronofsky Movie, Ranked

The 1990s saw the emergence of many young, transgressive filmmakers whose experimentation and inventiveness took the industry by storm. Darren Aronofsky was among this new class of directors, many of whom built their careers off of an enthusiastic screening for their debut feature at the Sundance Film Festival. However, Aronofsky was distinct from contemporaries like Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater, Noah Baumbach, or David O. Russell because his work was deliberately anti-commerical, and at times defiantly obtuse. Rather than using lurid content for the sake of stylized entertainment, Aronofsky seemed committed to telling bleak, upsetting stories about human misery.

Aronofsky may have been labeled as a provocateur, but the maturation of his career has revealed him to be a humanist. Love them or hate them, Aronofsky’s films have attempted to visualize aspects of the human condition that aren’t often given a cinematic spotlight. As punishing as his work can be, Aronofsky is a dramatist at heart, and his films have frequently literalized their mythic and religious undertones. Although it’s up for debate which of Aronofsky’s works are guilty of indulgence, he has yet to direct a feature that isn’t worthy of analysis.

There’s a consistency to Aronofsky’s output that is admirable, as he has yet to dip his toes into the streaming ecosystem or prestige television. Although Black Swan is the only film that earned him personal recognition from the Academy Awards, Aronofsky’s name is itself a draw; Noah was a surprising global smash hit, and The Whale became one of the most profitable films in A24’s history. In an era where great artists are forced to cut corners, Aronofsky has seemingly never compromised his vision. In honor of this week’s release of Caught Stealing, here is every film directed by Darren Aronofsky, ranked from worst to best.

9. Mother! (2017)

Although Aronofsky has touched on the complexities of faith within all of his work, Mother! offered his most critical analysis of religious literature. Noah may have used the stories of the Bible to make grandiose statements about mankind’s relationship with nature, but with Mother!, Aronofsky examined the behavior of God himself through a narcissistic, unnamed artist played by Javier Bardem. Aronofsky’s version of the creator wasn’t just a dominant figure of toxic masculinity, but a narcissistic maestro who was too blinded by ego to see the misery suffered by his wife (Jennifer Lawrence), a stand-in for Mother Earth. Even for those who didn’t grow up going to Sunday school, the religious allusions become fairly apparent by the point that Ed Harris and Michelle Pfeiffer show up as sleazy versions of Adam and Eve, respectively.

The notion that God is an artist who is willing to forgive the evils committed by mankind out of pride is a fascinating concept. Unfortunately, Aronofsky is incapable of any hints of subtlety, as his characters exist in a vacuum where there is no attempt to interpret the Biblical stories in a non-literal way. It’s the rare example of Aronofsky’s use of violence being fruitless, as the home invasion set-up contains no tension because there is never a reasonable expectation of a peaceful resolution.

When considering how gentle Aronofsky has generally been in his depiction of complex interpersonal relationships, the dynamic between Bardem and Lawrence rings surprisingly false, as the film never presents a reason for their initial attraction. To her credit, Lawrence does her best with the material, in which she struggles to give individuality to a character who is defined by abuse. Perhaps, the fact that Lawrence received the bulk of the criticism for Mother! proved Aronofsky’s point.

8. Noah (2014)

The flipside of the cheeky allegories of Mother! is Noah, a surprisingly straightforward adaptation of the most iconic story from the Book of Genesis. Although Noah is operatic and epic in a way that Aronofsky had never been before, it also couldn’t be confused for the type of verbatim Christian cinema that followed The Passion of the Christ. Noah is at times a grotesque monster movie, an intimate family story, and a mournful cry for environmentalism, even if it also operates as a mythic adventure with the scale and scope comparable to The Lord of the Rings.

There was no use in seeing someone of Aronofsky’s talents tackle this material if it wasn’t filtered through his perspective, and Noah does contain much of the same psychological terror and apocalyptic anxieties that were found in The Fountain and Pi. Although any depiction of such sensitive material would have likely inspired some form of controversy, Aronofsky is remarkably progressive in drawing from multiple sources of inspiration, including religious texts beyond the Bible.

Noah is at its best when it incorporates experimental, visual reflections on destruction and rebirth, as Aronofsky had never been given the opportunity to use computer-generated imagery in such an artful way before. Although the human drama lacks the intimacy found in his earlier films, Noah does have interesting ideas about the guilt and responsibilities passed down from one father to another; even if Anthony Hopkins’ role as Methuselah is scenery-chewing at its finest, there’s a poignancy to the parallel stories of Noah (Russell Crowe) and his son, Ham (Logan Lerman). Even if Noah saw Aronofsky working outside his comfort zone, it deserves credit for being far more interesting than a more traditional illustration would have ever been.

7. The Whale (2022)

It may be a slight overreach to say that The Whale is the most polarizing entry in Aronofsky’s canon, but it may be the film that inspired the most extreme reactions with regards to intentionality. While some saw the adaptation of Samuel D. Hunter’s controversial play as an empathetic, moving call for empathy, others saw it as deeply exploitative and cruel. At its best, The Whale offers a complex analysis of how shame is brought upon by sexuality, religion, abandonment, and a fear to disrupt the status quo. At its worst, The Whale is guilty of the same stigmatized dehumanization of its subject that it was seemingly attempting to criticize.

It would be impossible to discuss The Whale without mentioning the extraordinary, Academy Award-winning performance by Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a morbidly obese English teacher bound to his lonely apartment in Idaho. It was a stroke of genius on Aronofsky’s part to find one of the most sincere leading men of his generation and give him the opportunity to play a character who is deliberately repulsive; although the film is quite cynical in its suggestion that Charlie would be forced to lurk within the shadows of civil society, its most profound idea is that the the deepest hatred he faces is self-imposed. Fraser brings a remarkable degree of sensitivity and personality to the role, even when Charlie’s body is used to invoke disgust. Unfortunately, this nuance does not extend to the supporting cast, as Fraser’s talented co-stars Sadie Sink and Ty Simpkins are unable to elevate their thinly written characters.

Aronofsky’s decision to retain the restrictive environment of the source material is the film’s most impressive achievement, yet also its biggest detriment. Although at times the isolation and claustrophobia justifies the exaggerated emotions on display, the action often feels stagnant, as Aronofsky’s more creative attempts to find new angles feel needlessly athletic. If anything, the ham-fisted spiritual visuals of the film’s final moments perfectly represent whose work in The Whale is most impressive; Aronofsky may have yielded mixed results with challenging material, but he gave Fraser the platform to do the most transcendent work of his career.

6. Caught Stealing (2025)

“Fun” is the last word that most Aronofsky films would seemingly ever be associated with, and Caught Stealing is far from a traditional crime caper in the vein of Elmore Leonard or Dashiell Hammett. It’s certainly Aronofsky’s most entertaining film ever, if only for how dexterously it avoids the precautions that seem inherent to the subgenre. The story of a charming underachiever caught in over his head isn’t particularly groundbreaking, but what is subversive is the consequential grittiness Aronofsky bakes into the film. Caught Stealing is a film with no euphemisms or conveniences, as Austin Butler’s Hank Thompson goes through hell after being caught up in a gang rivalry in 1998’s New York.

It’s somewhat amusing that Arofonksy can now make a period piece about the year when his first film was released, and Caught Stealing is delightfully indulgent in fleshing out the brash, confrontational attitude of Rudy Gulinani’s reign. Although the commitment to realism is what defined much of Aronofsky’s early work, Caught Stealing makes the curious choice to make Hank a grounded character who is thrust within a superficial world; he may have trauma and regrets that feel very real, but he’s so unequipped for a life of crime that the conspiracy he finds himself at the center of feels entirely surreal. This heightened approach allows Caught Stealing to make the most of its conventions, as each shocking death or unusually timed joke is felt through Butler’s compelling turn as a former high school baseball star.

The sporadic nature of Caught Stealing may be baked into the approach, as Hank’s alcoholism is represented through highs and lows within the film’s energy; at times, it’s easy to be desensitized to the madness that ensues, as Hank has not entirely processed the series of bad decisions that lead to his current predicament. It’s imperfect, as Aronofsky’s grasp on his female characters is still disappointingly shallow, and some of the sight gags feel needlessly mean-spirited. Nonetheless, Caught Stealing is a sign that Aronofsky has evolved, as he’s capable of making a fine piece of studio entertainment that doesn’t feel inundated by executive notes.

5. The Fountain (2006)

After establishing a grounded, gritty sensibility within his first two films, Aronofsky took the most ambitious swing of his career with The Fountain. It was a project that miraculously survived multiple production difficulties, as Aronofsky was forced to rework the script after his initial $70 million budget was slashed, and original stars Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett dropped out. Even if the film’s financial disappointment didn’t stop it from earning a cult audience, there’s a sense that this is Aronofsky’s “one that got away”; although he offered up his own commentary after Warner Bros. removed it from the home media release, Aronofsky has yet to craft a director’s cut that achieved a scale comparable to his original vision.

The Fountain is paradoxically the most narratively complex and emotionally straightforward film of Aronofsky’s career. On a literal level, it’s an epic study of spirituality, science fiction, and mythmaking, and explores the quest for immortality over the course of three critical eras in human history. However, the most powerful hook in The Fountain is the heartbreaking burden placed upon Dr. Tommy Creo (Hugh Jackman) as he seeks a cure for his wife, Izzi (Rachel Weisz), who is dying from breast cancer. At times, the blend of Kubrickian symbolism and Spielbergian pathos is quite powerful, as it beautifully represents how humanity has been defined by its fear of death. However, Aronofsky’s inventiveness with match cuts, macro photography, and computer-generated imagery can feel consumed by their technical wizardry, making the focus of the narrative feel secondary.

It would be ignorant of Aronofsky’s goals with the film to describe any one section as “hokey,” but when it comes to pacing, the storylines set in 16th Century South America and deep into the intergalactic future are not as compelling as the more personal marital drama, in which Aronofsky clearly feels the most comfortable. Although there’s stunning moments in which all three timelines are intertwined, they’re so tonally distinct that the connections can feel disproportionate. A film like The Fountain could never be made today, as it required audiences to both open their hearts and engage with the omnipresent symbolism; even similarly ambitious projects like Interstellar and The Tree of Life could be framed as more traditional genre exercises. There may be a masterpiece within the footage of The Fountain that Aronofsky has compiled, yet not sanded down into a new cut. As of now, it stands as a curious object of cult affinity, which is made all the more interesting because of its imperfections.

4. Requiem for a Dream (2000)

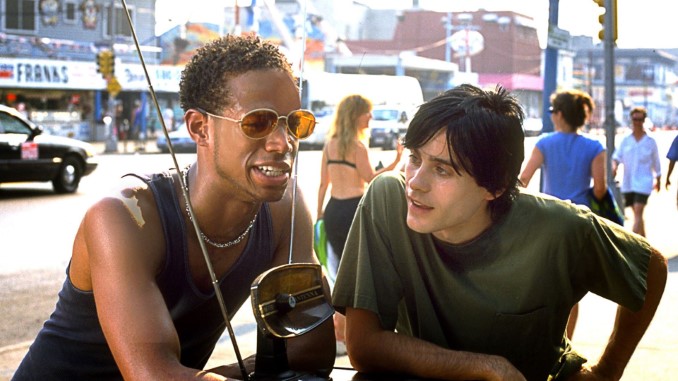

Aronofsky truly established himself as a generational talent with his bleakest, most challenging work, which has ranked on lists of “the most depressing films ever made” ever since its debut in 2000. Although the hallucinatory, haphazard style of editing that Aronofsky pioneered has often been a barrier to his audiences, Requiem for a Dream justified his most off-putting tendencies; unlike similarly themed “drug movies” of the 1990s, such as Trainspotting or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Requiem for a Dream didn’t depict the period of denial found in early stages of addiction. Rather, it was a film focused purely on ramifications, showing broken characters who had long given up on potential reclamation.

The cruelty Aronofsky shows to his characters in Requiem for a Dream does not feel exploitative because of the film’s rejection of common arguments about sobriety. Characters like Sara Goldfarb (Ellen Burstyn), Marion Silver (Jennifer Connolly), and Tyrone C. Love (Marlon Wayans) may have begun as addicts seeking to escape their life problems, but years of drug abuse has transformed them into dark doppelgangers of the people they once were. The creative visual flares, such as the unnerving handheld shots and Aronofsky’s trademark cross-cuts, help to embody the feeling of never being able to awake from a nightmare. Even if Requiem for a Dream can frequently feel grimly observational, a masterful score by Clint Mansell underlines the formal similarities between the characters, each of whom express an unwillingness to evolve.

As is often the case with hyperlink cinema, Requiem for a Dream is more effective in its totality than it is when broken down into individual segments; the omnipresence of dread and terror that viewers feel when the credits begin to roll is enough to distract them from a slightly overindexed performance by Leto, and storyline involving the Sicilian Mafia that doesn’t quite connect. However, the lasting reputation that Requiem for a Dream has as a “feel-bad classic” is deserved; it’s a film so effective at eliciting trauma that it’s become challenging to rewatch.

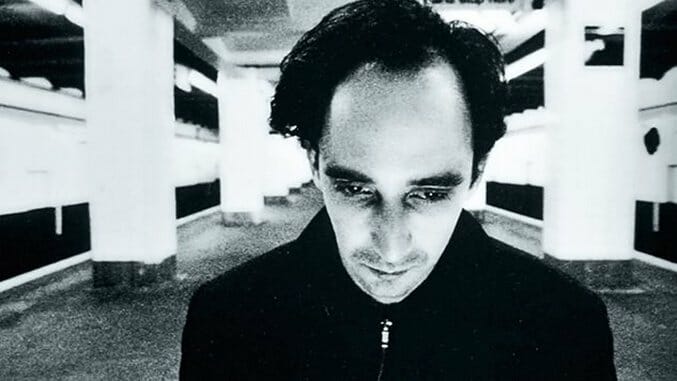

3. Pi (1998)

Some filmmakers emerged with a directorial debut that served as a rough outline for the ideas that they would better articulate in their subsequent careers, but Aronofsky kicked off his career with a fully-realized thesis statement about the obsession and torment that would dominate his body of work. Pi is a film so formally complex that it’s easy to overlook how dynamic it is as a narrative; with the character of Max Cohen (Sean Gullette), Aronofsky created a seemingly impenetrable protagonist who could be considered either a genius or a madman, depending on viewers’ interpretation. It’s a credit to both Aronofsky’s sharp writing and Guellette’s surprisingly vulnerable performance that Max is a character who feels genuinely tragic, even for those that struggle to follow the nuances of the plot.

Pi exists in a distorted version of reality in which mathematical theories, religious paranoia, graphic hallucinations, and broader conspiracy anxieties seem to all exist at once, making it possible to experience the same frustration and futility that Max does. Although the use of high-contrast, black-and-white reversals could have easily felt like a gimmick, Aronofsky uses the unusual visuals to emphasize Max’s strained attempts to apply binary logic to a seemingly irrational world. Even Mansell’s score, which includes more than a few inventive remixes, feels like an entirely unique work of art that captures the ambiguities of the premise.

Aronofsky has often been accused of emotional manipulation, as subtlety is not a trait that is common within his depictions of trauma and loss. However, Pi is surprisingly flexible, offering viewers multiple routes of engagement; while it’s packed with mathematical philosophy and historical commentary on anti-Semitism, those that want to engage with an internalized psychological drama are given multiple routes of entry. Although Aronofsky would obviously go on to work on projects of much larger scale, Pi was an indication of how unapologetically idiosyncratic his output would be.

2. Black Swan (2010)

It’s a novelty that Aronofsky’s greatest critical and commercial success is not only one of his best films, but among his most personal. The aspiration for perfection that defines Aronofsky’s protagonists is reflective of his own perspective, as every single entry in his catalog of work is rigorously outlined and given an extraordinary attention to detail. What is worth sacrificing for the sake of artistic greatness, and what transformations must be undergone to be unimpeachable? Perhaps these questions were asked of Aronofsky at some point, as they are at the heart of what makes Black Swan such an effective character study.

Nina (Natalie Portman) is a brilliant young dancer who has dedicated her entire life’s work to ballet, even if her domineering mother Erica (Barbara Hershey) is responsible for implementing that drive. In a haunting blend of folklore and psychological terror, Nina is forced not just to perform, but to become the titular character in Swan Lake, which requires access to both her inherent innocence and unrequited dark side. Nina’s commitment is never in doubt, but Aronofsky brilliantly questions whose expectations she’s living up to. Although Nina is drawn to a more aggressive side of her personality in order to both inhabit the role and silence her doubters, she also draws upon a lingering rage that has built upon a lifetime of being judged.

Portman’s full-bodied performance is worthy of the Academy Award that she won, as she committed to the type of laborious training that one would expect from an Aronofsky film. Even if ballet is simply a medium in which Aronofsky is able to make more all-consuming statements about art and ambition, he shows a remarkable respect for the craft, as Black Swan engages with the concepts of duality and fragility that are inherent to the form. Even the most viscerally disturbing moments of Black Swan are poetic in a sense, as the film never slows down to explain its internal logic to viewers. Like a great ballet, Black Swan is astoundingly poignant, emotionally gripping, and gloriously melodramatic, and builds to a jaw-dropping finale that ends with the appropriate fanfare. Even if Aronofsky never needed public adulation to justify his output, the fact that Black Swan was so rapturously received is fitting for such an evident piece of self-analysis.

1. The Wrestler (2008)

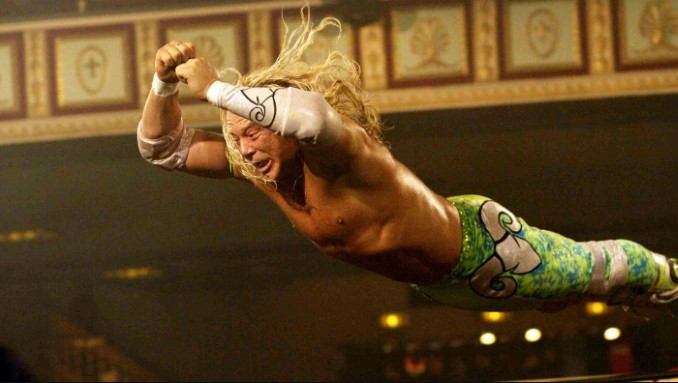

It’s fitting that Aronofsky’s best film is an unflinching drama about a tormented artist, working in a misunderstood profession, who has given up any hopes of redemption. After the commercial disaster of The Fountain, Aronofsky went back to his roots for an independent, $6 million character drama with a reclusive, temperamental star who had faded from public consciousness. Although The Wrestler was released when WWE had reached a new audience due to the stardom of figures like Dwayne Johnson and John Cena, Aronofsky offered a grim outlook on what professional wrestling actually looked like; regardless of what aspects of the sport were “real,” it left wrestlers with wounds that did not heal, and forgot about former stars as soon as they faced one too many losses.

Ironically, the lack of stylization is what distinguished The Wrestler, both in comparison to Aronofsky’s previous films and the popular depiction of wrestling. Rather than focusing on the precision of the stunts, The Wrestler offered an intimate, grueling look at the rigors faced by the human body. Mickey Rourke’s Robin Ramzinski, once known as “The Ram,” has become a nostalgic icon dismissed as another era’s hero. It’s not just the memories of success that have haunted Robin, but the reminder of what he gave up for his all-too brief moment in the spotlight. The parallels to Rourke’s own career were an essential part of the film’s narrative; considering how short-lived Rourke’s comeback ended up being, Aronofsky’s ability to get such a moving, vulnerable performance out of him is a miracle.

Although the religious undertones of Aronofsky’s earlier work is somewhat muted, The Wrestler does examine a different form of spirituality in the form of the larger-than-life personas of professional wrestlers. Robin may be a bruised, depressed man with an estranged daughter (Evan Rachel Wood) and a job at a strip club, but for the moments in which he becomes “The Ram,” an audience believes that he is a champion. The film’s analysis of the traumatic injuries suffered by wrestlers proved to be particularly timely, as was its acute analysis of the inherent instability of capitalism; while it was shot prior to the 2008 financial crash, The Wrestler embodied the terror of losing one’s essence overnight better than any other film released that year.

The terror of The Wrestler is as visceral as Black Swan and as disturbing as Requiem for a Dream, but it’s the weaponized empathy that makes Aronofsky’s work so singular. It’s not a film that idealizes Robin, yet it seeks to explain why he’s become so dependent on his chosen profession. Although not as cynical as one might expect from Aronofsky, nor as rousing as the sports film genre can be, The Wrestler is a story of flawed people and their persistence. Aronofsky is often labeled “obtuse” or “indulgent,” but The Wrestler shows a great director at his most earnest, heartbreakingly human.

Liam Gaughan is a film critic, writer, and entertainment journalist with over twelve years experience writing about popular culture. His bylines include Polygon, Dallas Morning News, Dallas Observer, High on Films, Central Track, Collider, Taste of Cinema, Slashfilm, and Movieweb. He also posts ramblings and thoughts on Letterboxd and X at @TheLiamGaughan.