In the American Machine We Trust: Rocky III and Sylvester Stallone’s Body

On its 40th anniversary, we revisit one of Stallone's less-heralded sequels.

In 2006, University of the Arts President Miguel Angel Corzo threatened to resign from the Philadelphia Art Commission. His complaint: Returning the Rocky statue to the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Citing the Commission’s intended purpose to “raise the standards” of Philadelphia, Corzo unintentionally rehashed an old standard of taste that was once applied to the Rocky franchise—to most franchises that reach five or six sequels—by default: This stuff shouldn’t be on the property of an art museum because this stuff isn’t art.

What Corzo likely wasn’t considering was the statue’s origin in Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky III, released Memorial Day weekend almost a quarter century earlier—nor did he likely consider the feelings of the film’s sensitive writer-director, who bequeathed the statue to the city following production by not taking it with him. Contained within that one gesture is the career-spanning gulf between Rocky Balboa’s humble background and Sylvester Stallone’s star-wielding influence—Stallone very sincerely giving the statue of himself to the city, as a token of the city’s generosity for all he’s arguably done for it, by just leaving it there. As the Association of Public Art vaguely describes, “After prolonged dispute, the city formally accepted the gift.”

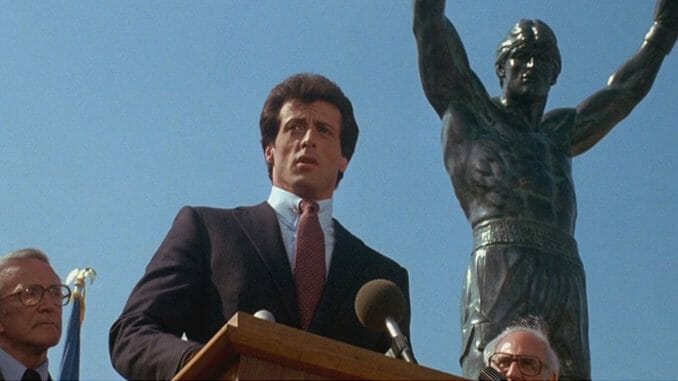

In 1982’s Rocky III, city officials unveil the statue during a ceremony for Philadelphia’s own son, Robert “Rocky” Balboa, the Italian Stallion and current Heavyweight Champion of the World. Adorned by adoring crowds, a marching band transforming Bill Conti’s “Gonna Fly Now” into diegetic fanfare, a bunch of dumbly grinning cops, Rocky’s trusty and crusty trainer Mickey (Burgess Meredith) and Rocky’s fur-donned wife Adrian (Talia Shire) finally beginning to feel comfortable in the finer things her husband’s vocation affords, Rocky stands sleek and triangular in flawless menswear at the top of the museum steps he made iconic in 1976’s Best Picture winner. He looks dapper but confused. This is the face Stallone gives Rocky so often, that of a man dumbfounded, some light not so long ago punched out of eyes which will never quite cease twinkling, but aren’t as lustrous as they once were. This is the face he wears when Clubber Lang (Mr. T) emerges from the crowd just as Rocky announces his retirement. Yelling up at both Rocky and the Rocky statue looming larger behind him, Lang challenges Rocky to a fight with real existential stakes:

Getting out while you can—don’t give this sucker no statue. Give him guts. I told y’all I wasn’t going away. You got your shot, now give me mine… Why don’t you tell these nice folks why you’ve been ducking me? Politics, man. This country wants to keep me down. Keep everybody weak. They don’t want a man like me to have the title, because I’m not a puppet like that fool up there…I’m telling you and everybody here, I’ll fight him anywhere, anytime, for nothing!

Mr. T, in his breakout role, follows up this public lashing by openly propositioning Adrian, traces of terror and disbelief lighting her face as a burly, mohawked Black man emasculates her comparatively small, lithe white husband in front of her, the city of Philadelphia and God. Rocky cannot allow this insult to stand; he throws his body into the crowd, clawing to get a piece of Lang. The steps that once represented how a street kid working odd jobs for the mob could transcend his status through sheer will and work are now the scene of a bitter confrontation over class and race. Metaphors are never less than obvious in Rocky movies, but suddenly, under the shadow of a larger-than-life reliquary for all of Sylvester Stallone’s mythos, Rocky is no longer the underdog.

This is all complicated by how mean Clubber Lang clearly is. In its opening, following the requisite reliving of the previous film’s final, climactic moments, Rocky III introduces Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger”—which would eventually become as ubiquitous as Bill Conti’s theme—to a montage of Rocky’s ascending fortune in the wake of KO-ing Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers). Where in Rocky II we waited around for Rocky to stumble his way through a few simple lines at his first commercial shoot—the lovable blue-collar galoot alien to the exigencies of fame—a few years and twice as many high-profile fights later, he seems natural in front of a camera, dividing his time between luxury branding and pretty easily punching the lights out of (predominantly Black) men in the ring.

Meanwhile, Clubber Lang seethes. First we see him in the audience, a head taller than everyone around him and one earring dripping with multicolored feathers, watching Rocky rack up one simple win after another. Then Stallone feeds Lang more time: We see him train in rooms festooned with mold and water damage, fueled by his animosity toward this sheltered Italian who only spars with easy targets. Then we get to watch Lang fight as, in split-screen, Rocky spends more and more time at home with his family, not in the ring and not in poisonous basements, Lang grimacing and covered in sweat while Rocky’s smiling and surrounded by wealth.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-