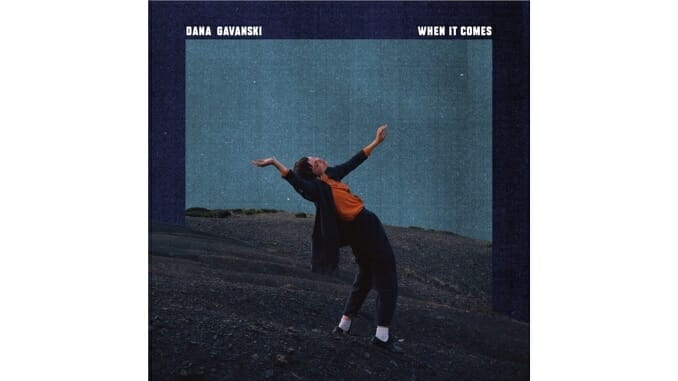

Dana Gavanski Revives Her Voice on When It Comes

The Canadian-Serbian singer/songwriter looks inward and pushes her folk-pop further on sophomore album

When singer/songwriter Dana Gavanski waltzes in on single “Under the Sky,” she presents the simple fact of what her new album When It Comes is at its core: “Songs that I sing / To pass unending time / It’s you and I / Under the sky.” One line plaintive and one line romantic, Gavanski’s collection of avant folk-pop is dissonant, moody and at times quite playful. In the wake of her debut album’s release, and in the process of crafting the songs that would soon make up When It Comes, Gavanski lost her voice, which proved more than a slight inconvenience for her. She came face-to-face with the pandemic isolation that has come to inform much of our interaction with the world around us today, and without her primary instrument, she found herself profoundly alone with her thoughts. On When It Comes, Gavanski reckons with some of those emotions she faced then and immediately thereafter with the kind of sensitivity, intellect and curiosity that she had honed on her debut, Yesterday Is Gone, while tenderly attaining new heights as a vocalist, producer and experimentalist.

When It Comes marks Gavanski’s second full-length on Full Time Hobby and Flemish Eye. Largely co-produced by Gavanski and her partner James Howard, the album leans heavier into an avant-pop direction with a vintage glow, reminiscent of peers Aldous Harding and Renata Zeiguer. Moog-heavy pop standouts sit alongside piano-forward tracks with poise and connectedness. Much of the record is shrouded in a reverberant sonic fog, cultivating the introspective, dreamlike state that Gavanski tapped into during her days estranged from her voice. Opener “I Kiss The Night” enters with a lamblike sweetness, beginning with just Dana and the piano, and growing into a more abundant track, ascending steadily with whimsy and awe like a colorful hot air balloon. Its growth into the polyphonic arrangement it becomes is reminiscent of a main character entering a frame and shining a light upon her context, awakening the surrounding atmosphere. “Bend Away and Fall” is more baroque, with prominent harpsichord features grounding the track in the past, even with the eerie synth flurries that hover above the chorus. Gavanski’s voice is an instrument among the others when she utters her distinctive “ahhs” in the bridge, which make haunting returns throughout the record and keep her voice center-stage.

It’s on “Letting Go” that Gavanski presents her mix of melancholy and progress, as she repeats mantras that, in her experience, function less as affirmations and more as reminders of her mind’s ability to trip her up. To add pizzazz to the mantra, she sends her voice soaring in exciting sequences that keep herself, and her listener, locked in. What the track exhibits in anxiety is matched by whimsy. Of course, as the subsequent track “Under the Sky” makes clear, she still has to let her mind wander. Gavanski’s memories swirl around her in a waltz, with an aura that ebbs between nostalgic and depressive, backed by arpeggiated synths that sound as if Beach House were loaded into a time machine. Her emotions remain as variegated as her instrumentation, which maintains its connection to ‘60s outsider pop while exploring jazzy arrangements in the album’s middle.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-