The 50 Greatest Albums of 1975

If 1974 was one of the weakest years of its decade, then 1975 was arguably the strongest. A lot of great cultural moments happened happened: Stevie Wonder won his first Album of the Year Grammy, Talking Heads played their first gig at CBGB, Gregg Allman and Cher got married, Simon & Garfunkel reunited on Saturday Night Live, and the Who broke the indoor concert attendance record. But some great albums came out that year, too. As is tradition here at Paste, we’ve assembled a list of which releases we think are the best. There’s a little something of everything in here, so I hope you leave this ranking as curious as you are frustrated by my work.

For this list, a few on-the-cusp albums are noticeably missing—namely Lou Reed’s Coney Island Baby, Michael Hurley’s Have Moicy!, and Heart’s Dreamboat Annie, all of which have documented releases in ‘75 and ‘76. For the sake of fairness, I’m going to save those albums for our list next year, since no one can seem to agree on when Coney Island Baby actually came out and Dreamboat Annie didn’t hit US shelves until ‘76. There are no live albums featured here, so please don’t be upset that notable KISS and Bob Marley titles are missing. I promise those records will be on another relevant list soon! So, without further ado, here are the 50 greatest albums of 1975. Let me know in the comments which albums are your favorite and which ones I shouldn’t have left behind.

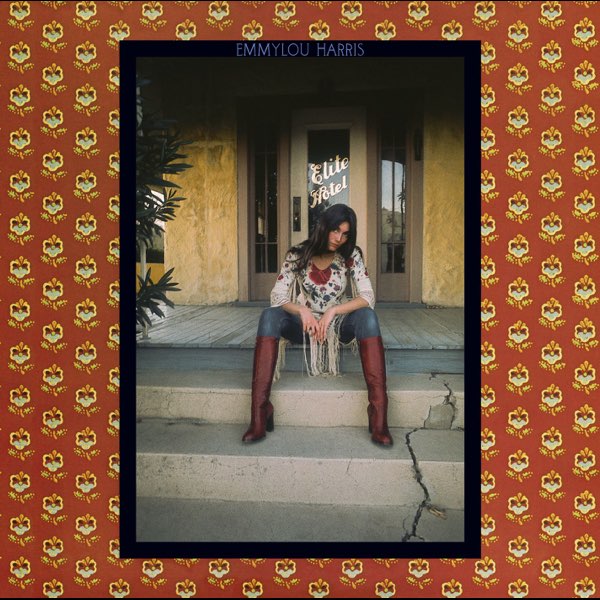

50. Emmylou Harris: Elite Hotel

Emmylou Harris made two great albums in 1975: Elite Hotel and Pieces of the Sky. While the latter has one of her best-known songs (“Boulder to Birmingham”), I find myself returning to Elite Hotel far more often. It was her first #1 album on the country charts, and her cover of Patsy Cline’s hit song “Sweet Dreams” went to #1, as did “Together Again.” She even found success in the pop realm when she remade the Beatles’ “Here, There and Everywhere.” There’s a good argument to be made that Harris was the vocal MVP of the ‘70s, thanks to her singing on albums by Gram Parsons, Neil Young, and Bob Dylan, and Elite Hotel is a great example of why her voice was so in-demand 50 years ago, as her work on these songs are free of imperfections. The standout remains “Together Again,” which finds Harris singing in harmony with Linda Ronstadt 12 years before they’d team up with Dolly Parton on Trio. —Matt Mitchell

Emmylou Harris made two great albums in 1975: Elite Hotel and Pieces of the Sky. While the latter has one of her best-known songs (“Boulder to Birmingham”), I find myself returning to Elite Hotel far more often. It was her first #1 album on the country charts, and her cover of Patsy Cline’s hit song “Sweet Dreams” went to #1, as did “Together Again.” She even found success in the pop realm when she remade the Beatles’ “Here, There and Everywhere.” There’s a good argument to be made that Harris was the vocal MVP of the ‘70s, thanks to her singing on albums by Gram Parsons, Neil Young, and Bob Dylan, and Elite Hotel is a great example of why her voice was so in-demand 50 years ago, as her work on these songs are free of imperfections. The standout remains “Together Again,” which finds Harris singing in harmony with Linda Ronstadt 12 years before they’d team up with Dolly Parton on Trio. —Matt Mitchell

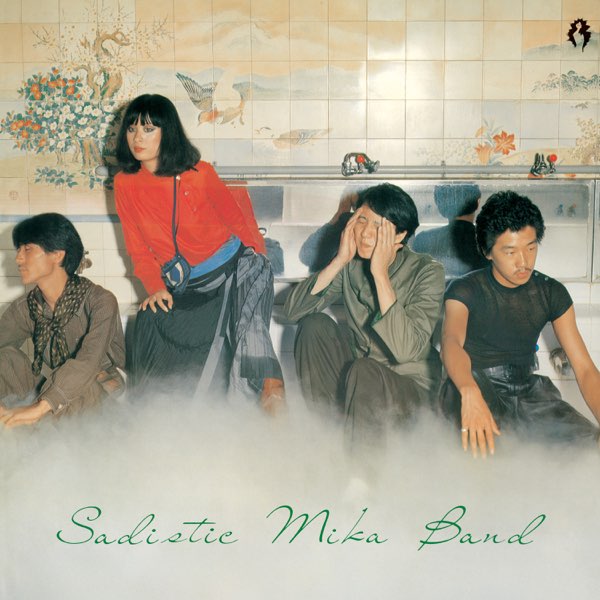

49. Sadistic Mika Band: Hot! Menu

Masayoshi Takanaka is one of the greatest living guitarists. But before he was a savant with a Stratocaster, he was in Kazuhiko Katō’s Sadistic Mika Band after the disbandment of his own Flied Egg group. Sadistic Mika Band were glam-rock pioneers in Osaka, and their third LP (and final until 1989), Hot! Menu, is a transportive, funky, delectable artifact from the pop’s pre-punk death rattle. They channeled Western trends, and the lead vocals of Mika (Katō’s wife) would later influence bands like Blondie and Strawberry Switchblade. In the UK, they were the opening act on Roxy Music’s Siren Tour, playing warm numbers like “Hey Gokigen Wa Ikaga” and “Wa-Kah! Chico” to their biggest-ever crowds. There’s jazz in this music, white-hot funk drenched in proggy overtures too. Takanaka’s guitars sweep, sway, and saturate, growing spacey in the company of Tsugutoshi Goto’s fretless bass before sprawling into melancholy when brushed against Mika’s sorrowed chirp on “Aquablue.” Then there is “Tequila Sunrise,” a vibrant finale full of field recordings and twangy guitar. The noise is always right beside us, even when Sadistic Mika Band sound like they’re performing from some faraway universe. —Matt Mitchell

Masayoshi Takanaka is one of the greatest living guitarists. But before he was a savant with a Stratocaster, he was in Kazuhiko Katō’s Sadistic Mika Band after the disbandment of his own Flied Egg group. Sadistic Mika Band were glam-rock pioneers in Osaka, and their third LP (and final until 1989), Hot! Menu, is a transportive, funky, delectable artifact from the pop’s pre-punk death rattle. They channeled Western trends, and the lead vocals of Mika (Katō’s wife) would later influence bands like Blondie and Strawberry Switchblade. In the UK, they were the opening act on Roxy Music’s Siren Tour, playing warm numbers like “Hey Gokigen Wa Ikaga” and “Wa-Kah! Chico” to their biggest-ever crowds. There’s jazz in this music, white-hot funk drenched in proggy overtures too. Takanaka’s guitars sweep, sway, and saturate, growing spacey in the company of Tsugutoshi Goto’s fretless bass before sprawling into melancholy when brushed against Mika’s sorrowed chirp on “Aquablue.” Then there is “Tequila Sunrise,” a vibrant finale full of field recordings and twangy guitar. The noise is always right beside us, even when Sadistic Mika Band sound like they’re performing from some faraway universe. —Matt Mitchell

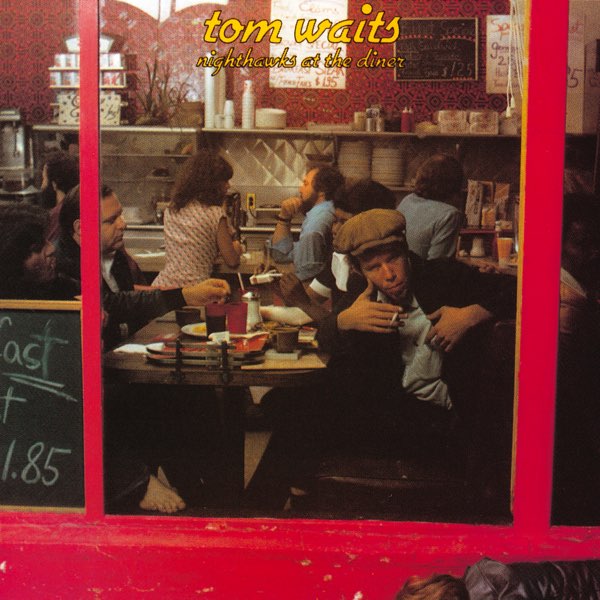

48. Tom Waits: Nighthawks at the Diner

Recorded over two days at the Record Plant in Los Angeles in front of a small audience, Tom Waits’ third album embodies the loose, improvisational mood of a jazz club weeknight. It’s 73 minutes of pure class and entertainment, sprawling and rambunctious like a Beat novel yet powerfully evocative and washed by near-dawn restlessness. Hearing these songs, you start to believe Waits might sing them forever. The 11-minute “Nighthawk Postcards (From Easy Street)” is the centerpiece, while “On a Foggy Night,” “Emotional Weather Report,” and “Big Joe and Phantom 309” surround the miscellany with inebriational travelogues of drunken pastorals. The music, sometimes nothing more than a backdrop for Waits’ overblown antics, is dramatic and pensive, as Pete Christlieb’s saxophone angles often into curiosity and Mike Melvoin’s piano twinkles with sell-out enthusiasm. Nighthawks at the Diner aches with pizzazz yet drowns in Viceroy smoke. Tom Waits is larger-than-life here, packed with detail and delighted by the claps and laughter before him. He’s like Frank Sinatra, until somebody picks him up off the floor. —Matt Mitchell

Recorded over two days at the Record Plant in Los Angeles in front of a small audience, Tom Waits’ third album embodies the loose, improvisational mood of a jazz club weeknight. It’s 73 minutes of pure class and entertainment, sprawling and rambunctious like a Beat novel yet powerfully evocative and washed by near-dawn restlessness. Hearing these songs, you start to believe Waits might sing them forever. The 11-minute “Nighthawk Postcards (From Easy Street)” is the centerpiece, while “On a Foggy Night,” “Emotional Weather Report,” and “Big Joe and Phantom 309” surround the miscellany with inebriational travelogues of drunken pastorals. The music, sometimes nothing more than a backdrop for Waits’ overblown antics, is dramatic and pensive, as Pete Christlieb’s saxophone angles often into curiosity and Mike Melvoin’s piano twinkles with sell-out enthusiasm. Nighthawks at the Diner aches with pizzazz yet drowns in Viceroy smoke. Tom Waits is larger-than-life here, packed with detail and delighted by the claps and laughter before him. He’s like Frank Sinatra, until somebody picks him up off the floor. —Matt Mitchell

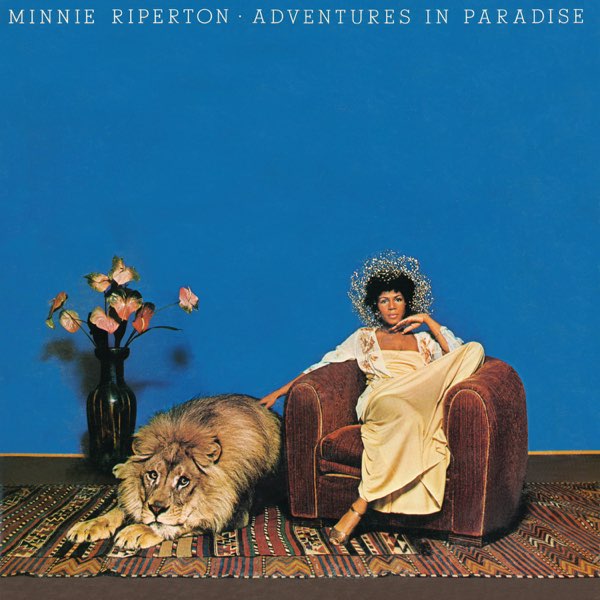

47. Minnie Riperton: Adventures in Paradise

A year prior, Minnie Riperton scored a gold record and Top 5 placement on the Billboard 200 with Perfect Angel—thanks to the #1 hit “Lovin’ You” and Riperton’s use of a whistle register. But it’s important to remember that her vocal range carries five octaves, and third album, Adventures in Paradise, is perhaps the greatest encapsulation of that dynamism. Perfect Angel co-producer Stevie Wonder was working on Songs in the Key of Life at the time, so Stewart Levine was hired to co-produce with Riperton and her husband, Richard Rudolph. The desire-driven slow jam of “Inside My Love” is playfully sensual and brimming with double entendres, while opening song “Baby, This Love I Have” saunters through Jim Horn and Tom Scott’s saxophone medley and Riperton’s glass-breaking falsetto and “Love and Its Glory” is a soulful teenage love drama, à la Romeo & Juliet for the disco era. —Matt Mitchell

A year prior, Minnie Riperton scored a gold record and Top 5 placement on the Billboard 200 with Perfect Angel—thanks to the #1 hit “Lovin’ You” and Riperton’s use of a whistle register. But it’s important to remember that her vocal range carries five octaves, and third album, Adventures in Paradise, is perhaps the greatest encapsulation of that dynamism. Perfect Angel co-producer Stevie Wonder was working on Songs in the Key of Life at the time, so Stewart Levine was hired to co-produce with Riperton and her husband, Richard Rudolph. The desire-driven slow jam of “Inside My Love” is playfully sensual and brimming with double entendres, while opening song “Baby, This Love I Have” saunters through Jim Horn and Tom Scott’s saxophone medley and Riperton’s glass-breaking falsetto and “Love and Its Glory” is a soulful teenage love drama, à la Romeo & Juliet for the disco era. —Matt Mitchell

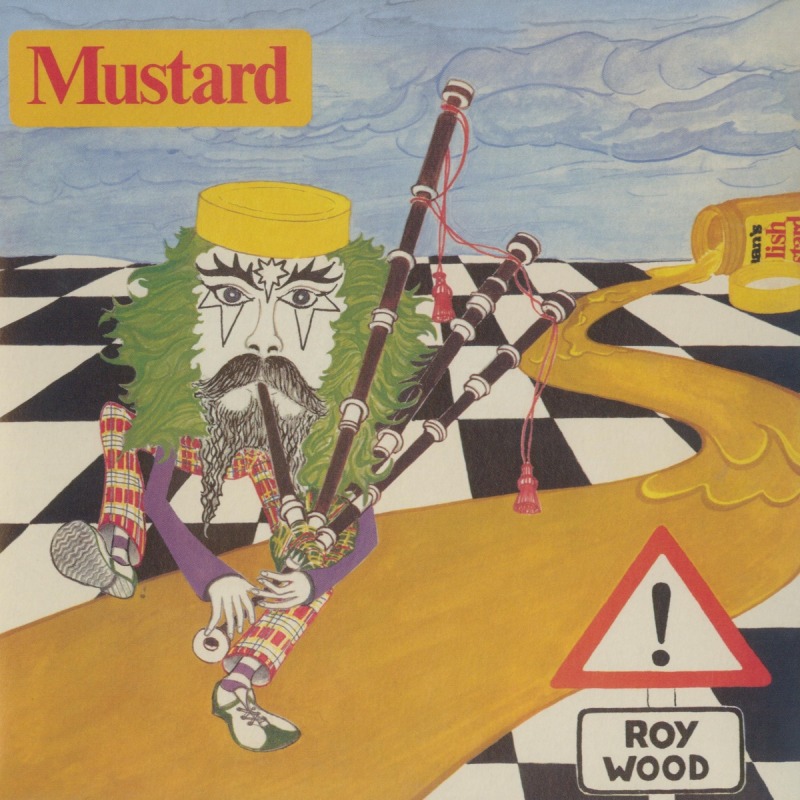

46. Roy Wood: Mustard

After co-founding Electric Light Orchestra with Jeff Lynne, the Move’s Roy Wood departed the band in 1972 despite playing on just a dozen tracks (he was uncredited on two of them). The truth about Wood, a madcap Englishman with a penchant for wigged-out glam-rock, was that his impulses were always just a bit too loose and left-of-center for Lynn’s always-perfect ELO sound. He would form the group Wizzard (not to be confused with Kid Cudi’s rock band WZRD) before investing in his own solo material. Wood was a disciple of Spector’s Wall of Sound production style, emulating smorgasbords of sub-genres in 40-minute packages. His second solo LP, Mustard, is an especially awesome fusion of glam, psych-rock, proto-metal, blues, and jazz. Wood pulled influence from the Andrews Sisters and the Beach Boys, painting strangeness into tracks like “The Rain Came Down on Everything” and “Why Does Such a Pretty Girl Sing Those Sad Songs.” Overlooked and maligned 50 years ago, Wood’s medley of eccentric noise has only become beloved in retrospect. Spend any amount of time with a recent Lemon Twigs record and you’ll catch my drift. —Matt Mitchell

After co-founding Electric Light Orchestra with Jeff Lynne, the Move’s Roy Wood departed the band in 1972 despite playing on just a dozen tracks (he was uncredited on two of them). The truth about Wood, a madcap Englishman with a penchant for wigged-out glam-rock, was that his impulses were always just a bit too loose and left-of-center for Lynn’s always-perfect ELO sound. He would form the group Wizzard (not to be confused with Kid Cudi’s rock band WZRD) before investing in his own solo material. Wood was a disciple of Spector’s Wall of Sound production style, emulating smorgasbords of sub-genres in 40-minute packages. His second solo LP, Mustard, is an especially awesome fusion of glam, psych-rock, proto-metal, blues, and jazz. Wood pulled influence from the Andrews Sisters and the Beach Boys, painting strangeness into tracks like “The Rain Came Down on Everything” and “Why Does Such a Pretty Girl Sing Those Sad Songs.” Overlooked and maligned 50 years ago, Wood’s medley of eccentric noise has only become beloved in retrospect. Spend any amount of time with a recent Lemon Twigs record and you’ll catch my drift. —Matt Mitchell

45. Bob Dylan & The Band: The Basement Tapes

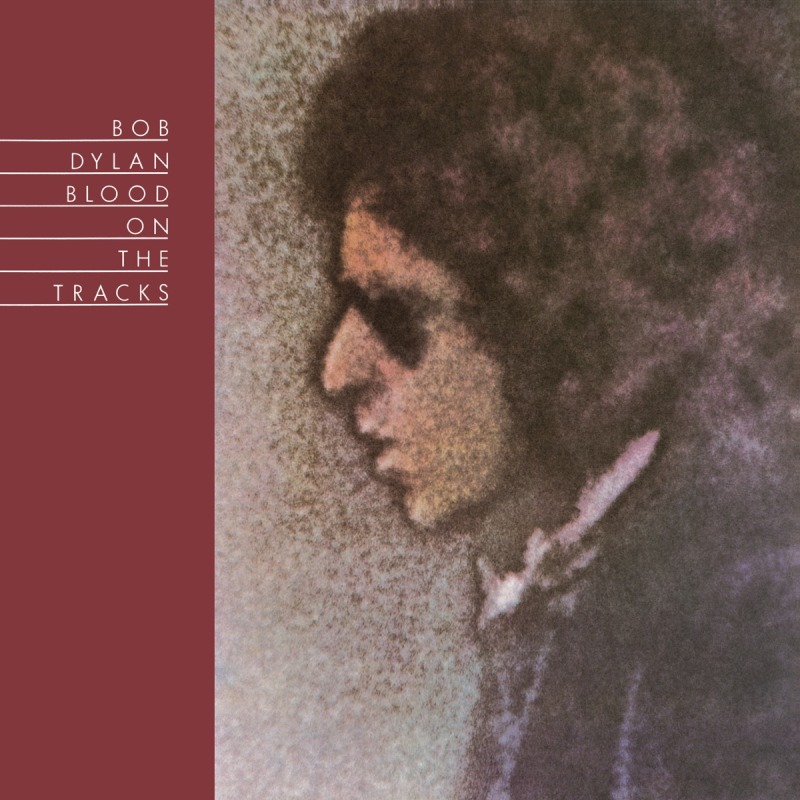

Originally recorded by Bob Dylan between 1967 and 1968 (and later overdubbed in 1975) with The Band (at the time known as The Hawks) after his motorcycle accident in 1966, The Basement Tapes is a rich, loose, and animated archival of 76 minutes of raucous music-making between some of the best performers of a generation. The story goes that over 100 songs were recorded during the sessions—including original material, covers, and traditional takes—but the 24 entries we get on The Basement Tapes are some of the most inventive musings Dylan ever had a hand in finishing. In hindsight, it’s clear just how crucial these songs bridged two eras of Dylan’s career, helping him move on from the poetic, organ-and-electric-guitar rock and roll of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde to the Americana and country stylings that would influence John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. The heavy hitter from the batch is “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” but songs like “This Wheel’s On Fire,” “Yazzo Street Scandal,” and “Goin’ to Acapulco” are incredibly fun moments to revisit. —Matt Mitchell

Originally recorded by Bob Dylan between 1967 and 1968 (and later overdubbed in 1975) with The Band (at the time known as The Hawks) after his motorcycle accident in 1966, The Basement Tapes is a rich, loose, and animated archival of 76 minutes of raucous music-making between some of the best performers of a generation. The story goes that over 100 songs were recorded during the sessions—including original material, covers, and traditional takes—but the 24 entries we get on The Basement Tapes are some of the most inventive musings Dylan ever had a hand in finishing. In hindsight, it’s clear just how crucial these songs bridged two eras of Dylan’s career, helping him move on from the poetic, organ-and-electric-guitar rock and roll of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde to the Americana and country stylings that would influence John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline. The heavy hitter from the batch is “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” but songs like “This Wheel’s On Fire,” “Yazzo Street Scandal,” and “Goin’ to Acapulco” are incredibly fun moments to revisit. —Matt Mitchell

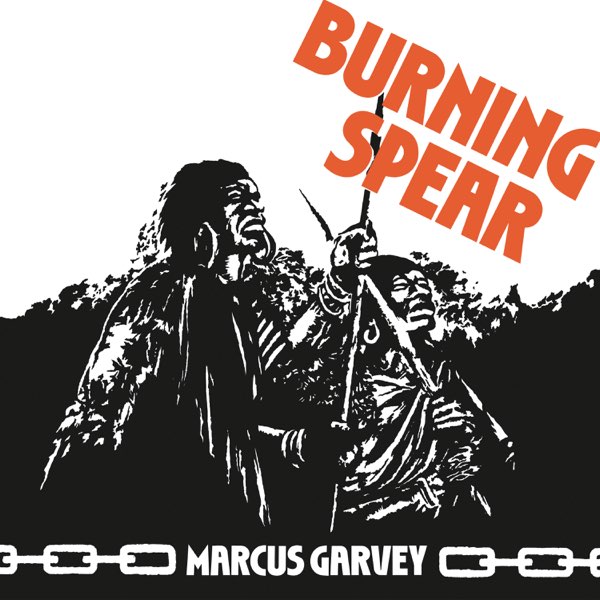

44. Burning Spear: Marcus Garvey

Burning Spear, the stage name of Rastafarian hero Winston Rodney OD, is among the most important dub and roots reggae musicians of the ‘70s. Rodney’s worldview was shaped by the teachings of political activist and Rastafari prophet Marcus Garvey, who founded the UNIA-ACL and was a Pan-Africanist and Black Nationalist in the early 20th century. Rodney was especially drawn to Garvey’s outlook on self-determination and, through the initial advising of Bob Marley, began recording his own music. His third album, Marcus Garvey, pays tribute to Garvey through emotional, politically-charged reggae and funk diatribes. Songs like “Live Good” and “Give Me” arrived in 1975 full of demands for reparations and fantasies of peace. Rodney’s 2,000-year proverbs weren’t just historical paeans—they were non-negotiables. —Matt Mitchell

Burning Spear, the stage name of Rastafarian hero Winston Rodney OD, is among the most important dub and roots reggae musicians of the ‘70s. Rodney’s worldview was shaped by the teachings of political activist and Rastafari prophet Marcus Garvey, who founded the UNIA-ACL and was a Pan-Africanist and Black Nationalist in the early 20th century. Rodney was especially drawn to Garvey’s outlook on self-determination and, through the initial advising of Bob Marley, began recording his own music. His third album, Marcus Garvey, pays tribute to Garvey through emotional, politically-charged reggae and funk diatribes. Songs like “Live Good” and “Give Me” arrived in 1975 full of demands for reparations and fantasies of peace. Rodney’s 2,000-year proverbs weren’t just historical paeans—they were non-negotiables. —Matt Mitchell

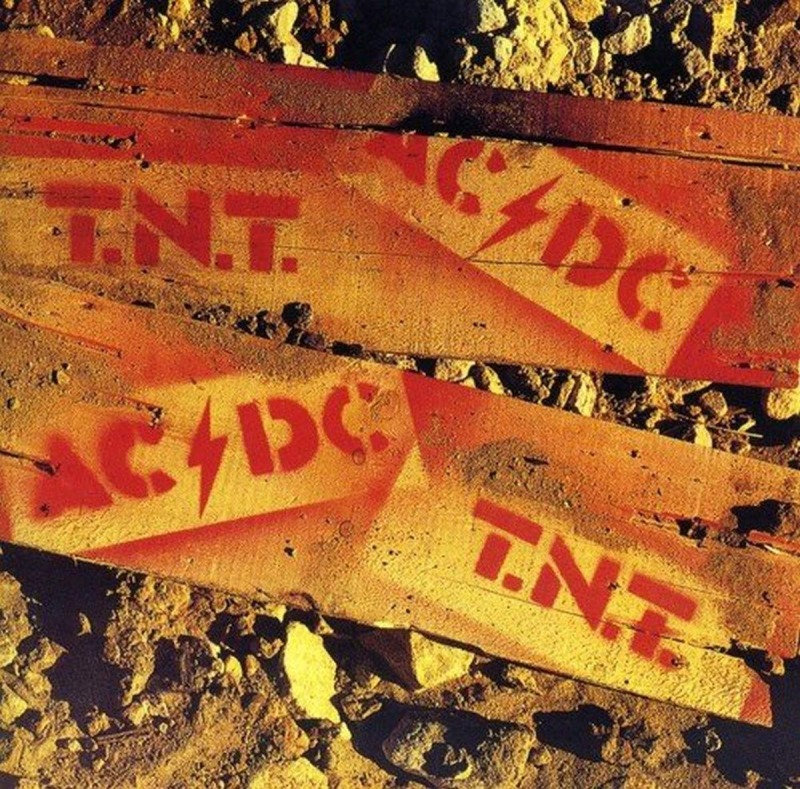

43. AC/DC: T.N.T.

The timeline of AC/DC’s first two albums is a nearly impossible logic puzzle to wrap your head around initially. High Voltage was their debut, seeing a release in Australasia in 1975 and globally in 1976. But the latter edition was more of an amalgamation of songs from the former and the band’s “second” album, T.N.T. If that still doesn’t make sense, don’t worry about it. T.N.T. is a great distillation of what made AC/DC so great in the beginning: head-splitting riffs, hedonistic lyrics, and the tandem of Bon Scott’s vocal debauchery and Angus Young’s enthralling licks. “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll),” cemented in history forever by School of Rock, is an opening track whose first vibrations are still going. But I’ve put a lot of stock in “The Jack,” “Rocker,” and “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl,” all of which put Scott’s seductive, playful bravado on display while Malcolm Young’s backline of rhythm guitar anchors his brother Angus’ machine gun riffs. T.N.T. is heretic glam rock free-falling into the clutches of hard-nosed, proto-metal shredding. Not a bad introduction to a band of twenty-something Aussies on diets of cigarettes, milk, and too-tight jeans, fronted by a school uniform-clad punk weighing 140 pounds soaking wet. —Matt Mitchell

The timeline of AC/DC’s first two albums is a nearly impossible logic puzzle to wrap your head around initially. High Voltage was their debut, seeing a release in Australasia in 1975 and globally in 1976. But the latter edition was more of an amalgamation of songs from the former and the band’s “second” album, T.N.T. If that still doesn’t make sense, don’t worry about it. T.N.T. is a great distillation of what made AC/DC so great in the beginning: head-splitting riffs, hedonistic lyrics, and the tandem of Bon Scott’s vocal debauchery and Angus Young’s enthralling licks. “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll),” cemented in history forever by School of Rock, is an opening track whose first vibrations are still going. But I’ve put a lot of stock in “The Jack,” “Rocker,” and “Can I Sit Next to You, Girl,” all of which put Scott’s seductive, playful bravado on display while Malcolm Young’s backline of rhythm guitar anchors his brother Angus’ machine gun riffs. T.N.T. is heretic glam rock free-falling into the clutches of hard-nosed, proto-metal shredding. Not a bad introduction to a band of twenty-something Aussies on diets of cigarettes, milk, and too-tight jeans, fronted by a school uniform-clad punk weighing 140 pounds soaking wet. —Matt Mitchell

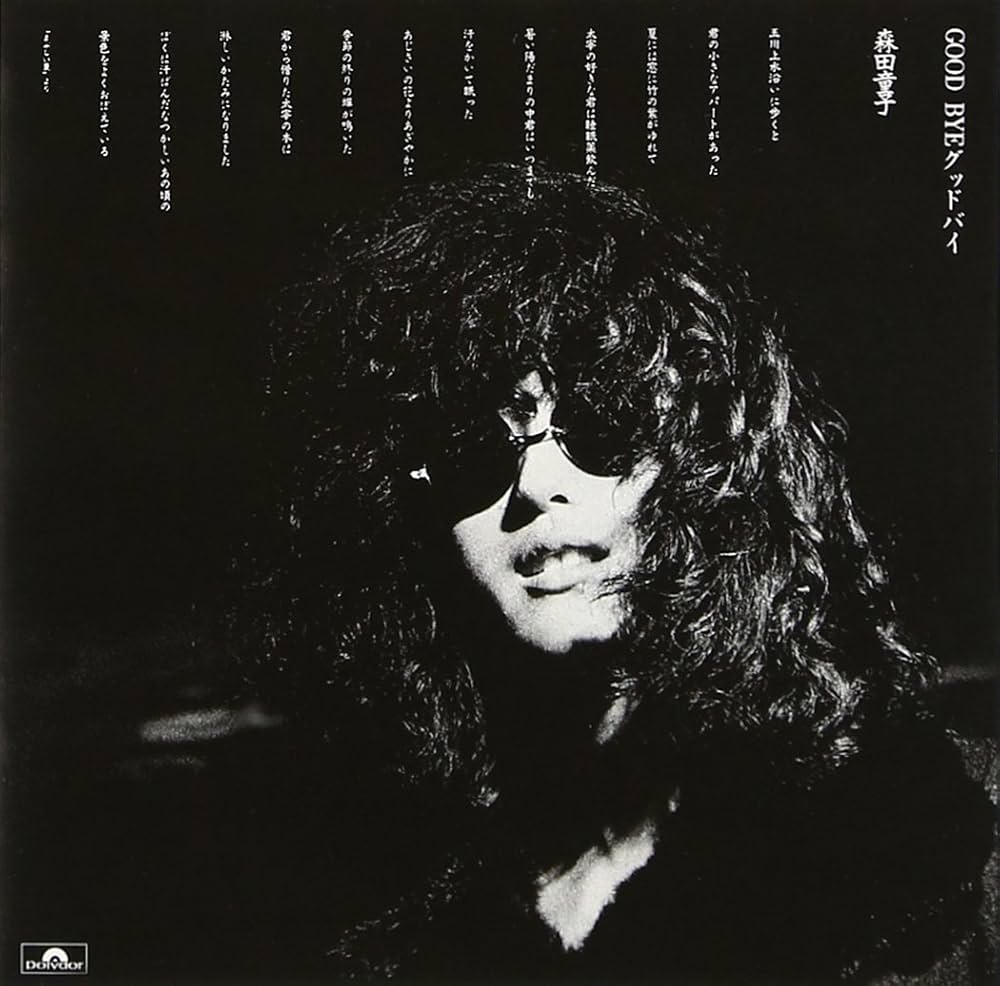

42. Doji Morita: Good Bye

Looking at the state of Japanese music in 1975, there were many threads being tugged at. Psychedelia and glam-rock were heavy on the mind, while electronica and synth-pop were nearly in focus. But let me regale you. I present: Doji Morita’s Good Bye, an album so wonderfully somber you may just weep without knowing any of the words. Morita was famously private, maybe one of the first great “anonymous rock stars.” And yet, her music was tremendously funereal and close-chested. Good Bye is chamber folk music unlike anything I’ve ever listened to, strands of bittersweet performance that transcend the language barrier. I can hear Morita singing, and I can feel her singing, too. The finger-picked melodies are potently elemental, and her voice could be, pardon my cliché, mistaken for an angel’s. Not much is known about Morita, but Good Bye has withstood the test and trends of time. —Matt Mitchell

Looking at the state of Japanese music in 1975, there were many threads being tugged at. Psychedelia and glam-rock were heavy on the mind, while electronica and synth-pop were nearly in focus. But let me regale you. I present: Doji Morita’s Good Bye, an album so wonderfully somber you may just weep without knowing any of the words. Morita was famously private, maybe one of the first great “anonymous rock stars.” And yet, her music was tremendously funereal and close-chested. Good Bye is chamber folk music unlike anything I’ve ever listened to, strands of bittersweet performance that transcend the language barrier. I can hear Morita singing, and I can feel her singing, too. The finger-picked melodies are potently elemental, and her voice could be, pardon my cliché, mistaken for an angel’s. Not much is known about Morita, but Good Bye has withstood the test and trends of time. —Matt Mitchell

41. Eagles: One of These Nights

Before the Eagles made “Hotel California” and were deemed terminally uncool by the most annoying rock and roll fans you’ll ever meet, they were a slam-dunk, top-tier commercial act. Everything they made went platinum, each album spawning multiple #1 hits. One of These Nights, their follow-up to 1974’s On the Border, is the last record to feature the band’s original lineup: Don Henley, Glenn Frey, Bernie Leadon, and Randy Meisner. Don Felder had joined the previous year, and Leadon, upset over the band’s pivot from country to chart-friendly rock music, would leave, opening a pathway for Joe Walsh to join in 1976. But One of These Nights is the hero of the Eagles’ catalog, producing three Top 10 singles—the title track, “Lyin’ Eyes,” and “Take It to the Limit”—selling 4 million copies, and winning a Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals Grammy Award. You can hear the Eagles turning into superstars in these songs. The popularity didn’t soil the deep cuts, either: The Felder-sung “Visions” and Frey and Henley’s “After the Thrill is Gone” are mini treasures waiting behind the smoke of “Lyin’ Eyes” and “Take It to the Limit” on side two. —Matt Mitchell

Before the Eagles made “Hotel California” and were deemed terminally uncool by the most annoying rock and roll fans you’ll ever meet, they were a slam-dunk, top-tier commercial act. Everything they made went platinum, each album spawning multiple #1 hits. One of These Nights, their follow-up to 1974’s On the Border, is the last record to feature the band’s original lineup: Don Henley, Glenn Frey, Bernie Leadon, and Randy Meisner. Don Felder had joined the previous year, and Leadon, upset over the band’s pivot from country to chart-friendly rock music, would leave, opening a pathway for Joe Walsh to join in 1976. But One of These Nights is the hero of the Eagles’ catalog, producing three Top 10 singles—the title track, “Lyin’ Eyes,” and “Take It to the Limit”—selling 4 million copies, and winning a Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocals Grammy Award. You can hear the Eagles turning into superstars in these songs. The popularity didn’t soil the deep cuts, either: The Felder-sung “Visions” and Frey and Henley’s “After the Thrill is Gone” are mini treasures waiting behind the smoke of “Lyin’ Eyes” and “Take It to the Limit” on side two. —Matt Mitchell

40. Tommy Bolin: Teaser

Tommy Bolin accomplished a lot in his 25 years, playing in Zephyr, James Gang, and Deep Purple in a seven-year span up until his death in 1976. Somewhere in there came his debut solo album, Teaser, a record so entrenched in career-spanning influence that its intricacies only get woven so deep. But that’s not a bad thing at all. These songs span realms of hard rock, blues, reggae, Latin music, and jazz, ultimately anchoring into a fast-paced, mostly instrumental spectacle. Horns cut through the solo on “Marching Powder,” a sequence that could go the distance with any moment from any track from any album on this list, and “People, People” and “Lotus” are two complex showcases of Bolin’s picking genius. But he wasn’t all licks and gusto, nor was he merely Ritchie Blackmore’s replacement. His songs had progressive signatures, his slide guitar was deft, and his vocals were proving to be remarkable, to say the least. Just check out the 5-minute “Dreamer,” a superstar-in-the-making effort that could have taken Bolin to the mainstream, had he lived long enough to get there. There’s a reason Van Halen liked to cover “The Grind” so much: You can’t go wrong with a record that whips major ass. —Matt Mitchell

Tommy Bolin accomplished a lot in his 25 years, playing in Zephyr, James Gang, and Deep Purple in a seven-year span up until his death in 1976. Somewhere in there came his debut solo album, Teaser, a record so entrenched in career-spanning influence that its intricacies only get woven so deep. But that’s not a bad thing at all. These songs span realms of hard rock, blues, reggae, Latin music, and jazz, ultimately anchoring into a fast-paced, mostly instrumental spectacle. Horns cut through the solo on “Marching Powder,” a sequence that could go the distance with any moment from any track from any album on this list, and “People, People” and “Lotus” are two complex showcases of Bolin’s picking genius. But he wasn’t all licks and gusto, nor was he merely Ritchie Blackmore’s replacement. His songs had progressive signatures, his slide guitar was deft, and his vocals were proving to be remarkable, to say the least. Just check out the 5-minute “Dreamer,” a superstar-in-the-making effort that could have taken Bolin to the mainstream, had he lived long enough to get there. There’s a reason Van Halen liked to cover “The Grind” so much: You can’t go wrong with a record that whips major ass. —Matt Mitchell

39. Rufus & Chaka Khan: Rufus featuring Chaka Khan

There’s an argument to be made that the best song from an album on this list is “Sweet Thing.” The lead single from Rufus and Chaka Khan’s fourth album together was a Top 5 hit on the Hot 100 and sold a million copies in the United States, further cementing the group’s legacy—as if Rags to Rufus and Rufusized hadn’t already a year prior. The jazz eccentrics, paired with templates of rock, funk, and soul, made Rufus unconventional titans of the ‘70s, and Khan’s singing offered a deeply emotional, mellow bouy to the band’s disco-minded. Khan was a superstar then, her presence on every track unfathomably transformative, especially when she screams through “Fool’s Paradise.” Thanks to Clare Fischer’s string arrangements and Bobby Watson’s rhythms, “Ooh I Like Your Loving” and “Circles” are bass-minded, symphonic dancefloor favorites, while Tony Maiden’s blistering lead lines on the Bee Gees’ “Jive Talkin’” close the LP out with a warm wealth of aura. —Matt Mitchell

There’s an argument to be made that the best song from an album on this list is “Sweet Thing.” The lead single from Rufus and Chaka Khan’s fourth album together was a Top 5 hit on the Hot 100 and sold a million copies in the United States, further cementing the group’s legacy—as if Rags to Rufus and Rufusized hadn’t already a year prior. The jazz eccentrics, paired with templates of rock, funk, and soul, made Rufus unconventional titans of the ‘70s, and Khan’s singing offered a deeply emotional, mellow bouy to the band’s disco-minded. Khan was a superstar then, her presence on every track unfathomably transformative, especially when she screams through “Fool’s Paradise.” Thanks to Clare Fischer’s string arrangements and Bobby Watson’s rhythms, “Ooh I Like Your Loving” and “Circles” are bass-minded, symphonic dancefloor favorites, while Tony Maiden’s blistering lead lines on the Bee Gees’ “Jive Talkin’” close the LP out with a warm wealth of aura. —Matt Mitchell

38. Black Sabbath: Sabotage

By 1975, it seemed like Black Sabbath had exhausted itself. The band’s first five records, from the self-titled through Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, were all tremendous, but only the Beatles had ever had six great releases in a row. The expectations were massive, and the interpersonal dynamics were crumbling: Wounded by coke addictions and a long, exhausting legal battle with their management team, Black Sabbath should have burst into flames on Sabotage—the title would have certainly been fitting enough. What ensued became some of the band’s heaviest work, including “Hole in the Sky” and “Megalomania.” This is a record written about, fueled by, and delivered with rage, which makes the synthy, buzzy “Am I Going Insane” a hell of an outlier song. Sabbath’s reign on hard rock would plummet by the time LP7, Technical Ecstasy, hit the shelves a year later, but Sabotage is a living document of four musicians falling apart. The music is eccentric, with metal structures infiltrated often by proggy swells, but every turned corner is disorienting in the strangest ways. —Matt Mitchell

By 1975, it seemed like Black Sabbath had exhausted itself. The band’s first five records, from the self-titled through Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, were all tremendous, but only the Beatles had ever had six great releases in a row. The expectations were massive, and the interpersonal dynamics were crumbling: Wounded by coke addictions and a long, exhausting legal battle with their management team, Black Sabbath should have burst into flames on Sabotage—the title would have certainly been fitting enough. What ensued became some of the band’s heaviest work, including “Hole in the Sky” and “Megalomania.” This is a record written about, fueled by, and delivered with rage, which makes the synthy, buzzy “Am I Going Insane” a hell of an outlier song. Sabbath’s reign on hard rock would plummet by the time LP7, Technical Ecstasy, hit the shelves a year later, but Sabotage is a living document of four musicians falling apart. The music is eccentric, with metal structures infiltrated often by proggy swells, but every turned corner is disorienting in the strangest ways. —Matt Mitchell

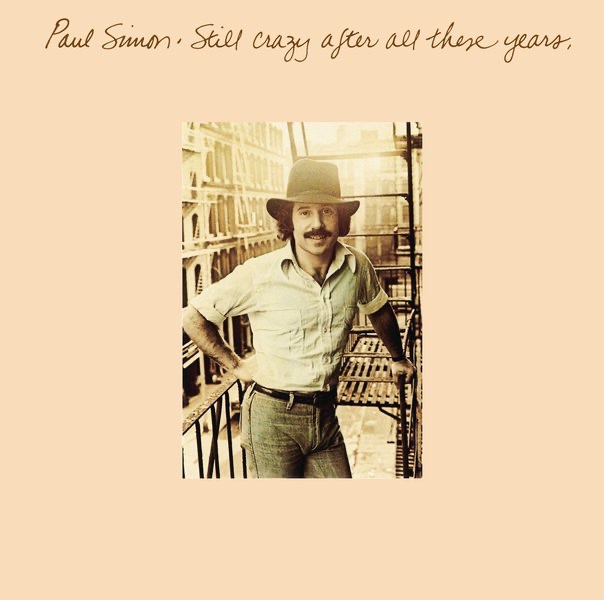

37. Paul Simon: Still Crazy After All These Years

I promise you, Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years is just as good on the 100th listen. Simon’s post-& Garfunkel solo career began well enough, thanks to hits like “Me & Julio Down By the Schoolyard” and “Kodachrome,” but this is where he finally started cooking for good. Even if he hadn’t made Graceland, an album like this is the type to cement someone’s legacy. Still Crazy After All These Years spawned four Top 40 hits—“50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” “Gone at Last,” “My Little Town,” and the title track—and won two Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year. I am especially partial to the sublime “My Little Town,” which features vocals from Art Garfunkel and really puts a great punctuation on the “divorce record” vibes of Still Crazy. My only critique of the record is that Simon left “Slip Slidin’ Away” off of it. But him performing the title track in a turkey suit on Saturday Night Live nearly makes up for that mistake. Nearly. —Matt Mitchell

I promise you, Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years is just as good on the 100th listen. Simon’s post-& Garfunkel solo career began well enough, thanks to hits like “Me & Julio Down By the Schoolyard” and “Kodachrome,” but this is where he finally started cooking for good. Even if he hadn’t made Graceland, an album like this is the type to cement someone’s legacy. Still Crazy After All These Years spawned four Top 40 hits—“50 Ways to Leave Your Lover,” “Gone at Last,” “My Little Town,” and the title track—and won two Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year. I am especially partial to the sublime “My Little Town,” which features vocals from Art Garfunkel and really puts a great punctuation on the “divorce record” vibes of Still Crazy. My only critique of the record is that Simon left “Slip Slidin’ Away” off of it. But him performing the title track in a turkey suit on Saturday Night Live nearly makes up for that mistake. Nearly. —Matt Mitchell

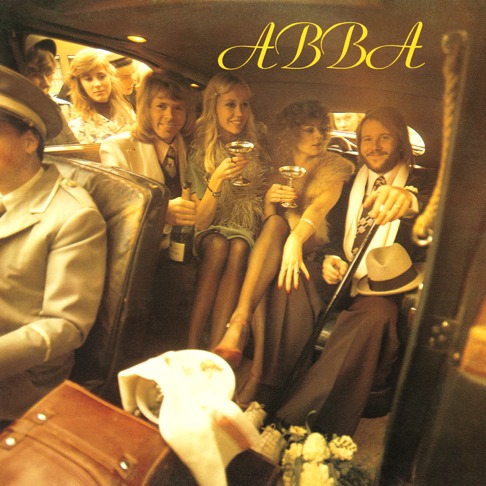

36. ABBA: ABBA

For some, ABBA’s cultural relevance didn’t begin until Arrival in 1976. But I implore you to turn back your clocks to a year prior and let the goodness of the Swedish quartet’s self-titled album wash over you. It featured seven (!) singles, including “I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do,” “Mamma Mia,” “I’ve Been Waiting for You,” and “So Long,” all of which are delightfully catchy. But whenever I am asked about my favorite ABBA song, my answer is the same as it’s been since I was a teenager: “SOS,” a composition so inspired by Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound instrumentation and Beach Boy harmonies that it nearly outshines its own reference points. To me, “SOS” marks the moment where ABBA became pop titans. I’m listening to ABBA right now and it’s the greatest album I’ve ever heard. —Matt Mitchell

For some, ABBA’s cultural relevance didn’t begin until Arrival in 1976. But I implore you to turn back your clocks to a year prior and let the goodness of the Swedish quartet’s self-titled album wash over you. It featured seven (!) singles, including “I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do,” “Mamma Mia,” “I’ve Been Waiting for You,” and “So Long,” all of which are delightfully catchy. But whenever I am asked about my favorite ABBA song, my answer is the same as it’s been since I was a teenager: “SOS,” a composition so inspired by Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound instrumentation and Beach Boy harmonies that it nearly outshines its own reference points. To me, “SOS” marks the moment where ABBA became pop titans. I’m listening to ABBA right now and it’s the greatest album I’ve ever heard. —Matt Mitchell

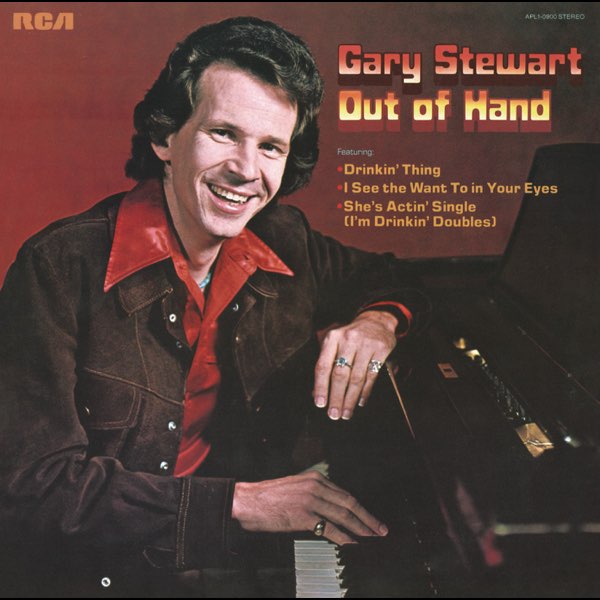

35. Gary Stewart: Out of Hand

Most Zoomers know of Gary Stewart thanks to Wednesday’s cover of his song “She’s Actin’ Single (I’m Drinkin’ Doubles),” but the Kentucky outlaw rarely gets the respect he deserves. His second LP, Out of Hand, is one of country music’s best efforts in the ‘70s, thanks to Stewart taking clear inspiration from Hank Williams and Jerry Lee Lewis, practicing a rockabilly sound with deadpan wit and honky-tonk bravado. “Drinkin’ Thing” is one of my favorite opening tracks ever, as Stewart, backed by the Jordanaires, mopes through the singalong like a drunken sad-sack clutching the bottle like a lover: “It’s a lonely thing, but it’s the only thing to keep a foolish man in love hangin’ on.” “I See the Want to in Your Eyes” lands closer to the country mainstream, thanks to a wallowing harmonica from Charlie McCoy, and “Back Sliders Wine” and “Sweet Country Red” are raucous bar stalwarts. Stewart, ever the anchoring, smooth-talkin’ shepherd of miserable, punch-drunk bombast, is backed by the damn-good trio of Harold Bradley, David Briggs, and Jerry Carrigan. And, yes, “She’s Actin’ Single,” curling in the color of Pete Drake’s steel guitar, could go 10 rounds with any song from any album on this list. —Matt Mitchell

Most Zoomers know of Gary Stewart thanks to Wednesday’s cover of his song “She’s Actin’ Single (I’m Drinkin’ Doubles),” but the Kentucky outlaw rarely gets the respect he deserves. His second LP, Out of Hand, is one of country music’s best efforts in the ‘70s, thanks to Stewart taking clear inspiration from Hank Williams and Jerry Lee Lewis, practicing a rockabilly sound with deadpan wit and honky-tonk bravado. “Drinkin’ Thing” is one of my favorite opening tracks ever, as Stewart, backed by the Jordanaires, mopes through the singalong like a drunken sad-sack clutching the bottle like a lover: “It’s a lonely thing, but it’s the only thing to keep a foolish man in love hangin’ on.” “I See the Want to in Your Eyes” lands closer to the country mainstream, thanks to a wallowing harmonica from Charlie McCoy, and “Back Sliders Wine” and “Sweet Country Red” are raucous bar stalwarts. Stewart, ever the anchoring, smooth-talkin’ shepherd of miserable, punch-drunk bombast, is backed by the damn-good trio of Harold Bradley, David Briggs, and Jerry Carrigan. And, yes, “She’s Actin’ Single,” curling in the color of Pete Drake’s steel guitar, could go 10 rounds with any song from any album on this list. —Matt Mitchell

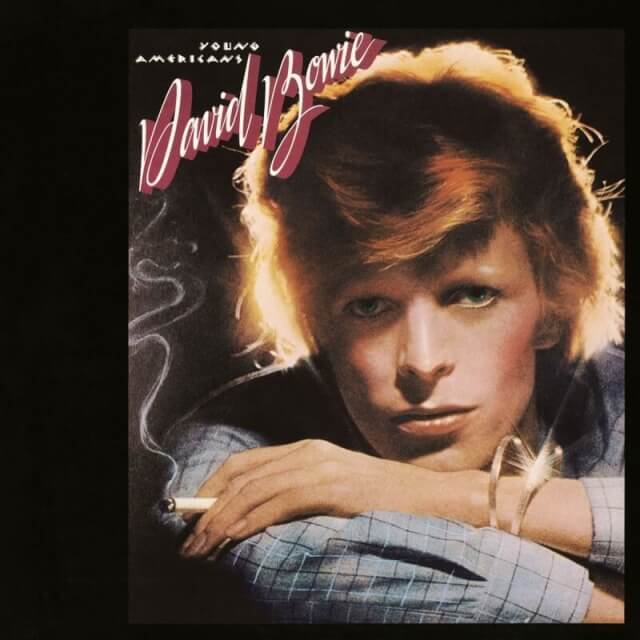

34. David Bowie: Young Americans

Young Americans is my favorite Bowie album, a strong return to center after the disappointing back-to-back of Pin-Ups and Diamond Dogs. But the latter deserves some praise, if only because its American tour stirred the Thin White Duke into a deep love for Philly soul—though he called it “plastic soul,” fittingly—and he even recorded part of the album at Sigma Sound in the city. Second single “Fame” became Bowie’s first #1 hit on the pop charts and landed him on Soul Train by the end of 1975. Gone was the dystopian, conceptual high-art of his previous albums. Bowie was doing sarcastic, easy-on-the-ears R&B music but with an orange-haired, English pop twist. On “Young Americans,” he asks: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?” What follows is a pastiche of transitional yet superb reference. The album is pointedly Beatles-coded—not in sound, but in reference. John Lennon sings backup on “Fame,” while Bowie covers “Across the Universe” and his background vocalists, including a young, unknown Luther Vandross, interpolate lyrics from “A Day in the Life” into the title track. In bursts of funk, blue-eyed soul, and punchy disco, Young Americans was the doorway into Bowie’s greatest chapter. —Matt Mitchell

Young Americans is my favorite Bowie album, a strong return to center after the disappointing back-to-back of Pin-Ups and Diamond Dogs. But the latter deserves some praise, if only because its American tour stirred the Thin White Duke into a deep love for Philly soul—though he called it “plastic soul,” fittingly—and he even recorded part of the album at Sigma Sound in the city. Second single “Fame” became Bowie’s first #1 hit on the pop charts and landed him on Soul Train by the end of 1975. Gone was the dystopian, conceptual high-art of his previous albums. Bowie was doing sarcastic, easy-on-the-ears R&B music but with an orange-haired, English pop twist. On “Young Americans,” he asks: “Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?” What follows is a pastiche of transitional yet superb reference. The album is pointedly Beatles-coded—not in sound, but in reference. John Lennon sings backup on “Fame,” while Bowie covers “Across the Universe” and his background vocalists, including a young, unknown Luther Vandross, interpolate lyrics from “A Day in the Life” into the title track. In bursts of funk, blue-eyed soul, and punchy disco, Young Americans was the doorway into Bowie’s greatest chapter. —Matt Mitchell

33. The Isley Brothers: The Heat is On

The 41-minute, multi-part The Heat is On is full of Ernie Isley’s guitar licks, Ronald Isley’s vamps, and the whole family’s onset disco worship. The Isley Brothers stir your soul before melting your face off, thanks to the unpredictable but delightfully smooth veers into funk, rock and roll, and doo-wop. “For the Love of You” is six minutes of sensual, quiet storm R&B, while the anti-authority “Fight the Power” peaked at #4 on the Hot 100 and wound up inspiring Public Enemy’s track of the same name. O’Kelly Isley takes the lead on “Sensuality,” letting his buttery falsetto shape the ballad’s sensible and soft grooves. But the MVP of The Heat is On is Chris Jasper, whose clavinet, Moog, and electric piano shape the backbone of every track. The album went to #1, making the Isley Brothers just the third Black band to do so, after Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire. —Matt Mitchell

The 41-minute, multi-part The Heat is On is full of Ernie Isley’s guitar licks, Ronald Isley’s vamps, and the whole family’s onset disco worship. The Isley Brothers stir your soul before melting your face off, thanks to the unpredictable but delightfully smooth veers into funk, rock and roll, and doo-wop. “For the Love of You” is six minutes of sensual, quiet storm R&B, while the anti-authority “Fight the Power” peaked at #4 on the Hot 100 and wound up inspiring Public Enemy’s track of the same name. O’Kelly Isley takes the lead on “Sensuality,” letting his buttery falsetto shape the ballad’s sensible and soft grooves. But the MVP of The Heat is On is Chris Jasper, whose clavinet, Moog, and electric piano shape the backbone of every track. The album went to #1, making the Isley Brothers just the third Black band to do so, after Ohio Players and Earth, Wind & Fire. —Matt Mitchell

32. Jackie McLean: Jacknife

The recordings on Jackie McLean’s Jacknife in 1975 were captured 10 years prior, in two sessions a year apart at the Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, NJ. The music was shelved, only to be repackaged as a double-LP by Blue Note. One half of the album features the trio of Lee Morgan, Charles Tolliver, and McLean, while the other half finds a then-33-year-old McLean as the sole horn in focus. But the saxophonist is delivering on some of his best material here, namely during the 12-minute “On the Nile,” which combines Willis’ rapturous piano melody with Tolliver’s warbling trumpet, patched together by McLean’s sax harmony, which conquers the angular “Jacknife” and nurtures the swaying, boppy “Blue Fable.” The horn solos and harmonic piano lines meld often, turning imperfect segments into small miracles. —Matt Mitchell

The recordings on Jackie McLean’s Jacknife in 1975 were captured 10 years prior, in two sessions a year apart at the Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, NJ. The music was shelved, only to be repackaged as a double-LP by Blue Note. One half of the album features the trio of Lee Morgan, Charles Tolliver, and McLean, while the other half finds a then-33-year-old McLean as the sole horn in focus. But the saxophonist is delivering on some of his best material here, namely during the 12-minute “On the Nile,” which combines Willis’ rapturous piano melody with Tolliver’s warbling trumpet, patched together by McLean’s sax harmony, which conquers the angular “Jacknife” and nurtures the swaying, boppy “Blue Fable.” The horn solos and harmonic piano lines meld often, turning imperfect segments into small miracles. —Matt Mitchell

31. Thin Lizzy: Fighting

Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak is forever on hard rock’s syllabus, but the Irish band couldn’t have made it there without first releasing Fighting, their transformative, breakout record. It’s the inaugural installment in a tremendous five-album run, and an introduction to the twin guitars of Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson, who’d join vocalist/bassist/producer Phil Lynott in creating one of the strongest musical menageries of the ‘70s—Thin Lizzy spun the blues into folk music, and they spun folk music into hard rock, and they spun hard rock into pop. You can hear the scuzzy, head-rattling benchmarks that Thin Lizzy would scratch at on “Jailbreak” (“Suicide”), while the band put their own bluesy, metallic spin on East Coast jazz-rock (“For Those Who Live to Love”). The album opens with an epic cover of Bob Seger’s “Rosalie” that mellows out with the terrific “Wild One” lick and boogies up in the Brian Robertson-penned “Silver Dollar.” But what makes Fighting a quintessential 1975 record is “Freedom Song,” Thin Lizzy’s greatest post-“Whiskey in the Jar” effort—a then-radically heroic Black Power protest anthem that emphasized the anti-authoritarian rock and roll foundations of blood, sex, and defiance. It’s as tough and necessary now as it was 50 years ago. —Matt Mitchell

Thin Lizzy’s Jailbreak is forever on hard rock’s syllabus, but the Irish band couldn’t have made it there without first releasing Fighting, their transformative, breakout record. It’s the inaugural installment in a tremendous five-album run, and an introduction to the twin guitars of Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson, who’d join vocalist/bassist/producer Phil Lynott in creating one of the strongest musical menageries of the ‘70s—Thin Lizzy spun the blues into folk music, and they spun folk music into hard rock, and they spun hard rock into pop. You can hear the scuzzy, head-rattling benchmarks that Thin Lizzy would scratch at on “Jailbreak” (“Suicide”), while the band put their own bluesy, metallic spin on East Coast jazz-rock (“For Those Who Live to Love”). The album opens with an epic cover of Bob Seger’s “Rosalie” that mellows out with the terrific “Wild One” lick and boogies up in the Brian Robertson-penned “Silver Dollar.” But what makes Fighting a quintessential 1975 record is “Freedom Song,” Thin Lizzy’s greatest post-“Whiskey in the Jar” effort—a then-radically heroic Black Power protest anthem that emphasized the anti-authoritarian rock and roll foundations of blood, sex, and defiance. It’s as tough and necessary now as it was 50 years ago. —Matt Mitchell

30. The Rocky Horror Picture Show

Rocky Horror—the stage show, the film, or the midnight screenings—is not everyone’s cup of fishnets. That’s probably a good thing; as the character Dr. Scott observes, “society must be protected.” (Kiss-ass!) That said, I’ve yet to find a pair of ears that can’t appreciate something in the music. In the early ‘70s, Richard O’Brien cobbled together the simple songs and stock narrative that would become The Rocky Horror Picture Show between gigs as a struggling London actor. He pulled most of the subject matter right from his own boyhood fascinations: rock ‘n’ roll, B-horror movies, comic books, weightlifting magazines and lingerie ads. As a result, Rocky’s songs offer something for almost everyone. The B-movie roll call of “Science Fiction/Double Feature” drips with almost lustful nostalgia for a bygone era of celluloid schlock and movie palaces while “I’m Going Home” pits Frank as our fave fallen alien this side of Bowie. Meat Loaf’s “Hot Patootie” leaves tire tracks down the backs of Elvis and Buddy Holly before skidding into a teen cautionary tale (“Eddie”) befitting a lowdown, cheap, little punk. There’s cornball romance (“Dammit Janet”), sexual awakenings (“Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch Me”) and all the glam decadence your steamy loins can stand as Tim Curry makes the entire galaxy wet on “Sweet Transvestite.” There’s even a faux dance craze that turned out to be, get this, an actual global sensation. (We’re looking at you, Time Warp.) It’s a compilation, nay a simmering cauldron, of familiar sounds, classic themes and juvenilia spiked with some elusive ingredient that empowers even the meekest among us to slip on a wobbly pair of pumps and declare ourselves the baddest bitch in space—or at least the biggest hotdog in the castle. —Matt Melis

Rocky Horror—the stage show, the film, or the midnight screenings—is not everyone’s cup of fishnets. That’s probably a good thing; as the character Dr. Scott observes, “society must be protected.” (Kiss-ass!) That said, I’ve yet to find a pair of ears that can’t appreciate something in the music. In the early ‘70s, Richard O’Brien cobbled together the simple songs and stock narrative that would become The Rocky Horror Picture Show between gigs as a struggling London actor. He pulled most of the subject matter right from his own boyhood fascinations: rock ‘n’ roll, B-horror movies, comic books, weightlifting magazines and lingerie ads. As a result, Rocky’s songs offer something for almost everyone. The B-movie roll call of “Science Fiction/Double Feature” drips with almost lustful nostalgia for a bygone era of celluloid schlock and movie palaces while “I’m Going Home” pits Frank as our fave fallen alien this side of Bowie. Meat Loaf’s “Hot Patootie” leaves tire tracks down the backs of Elvis and Buddy Holly before skidding into a teen cautionary tale (“Eddie”) befitting a lowdown, cheap, little punk. There’s cornball romance (“Dammit Janet”), sexual awakenings (“Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch-a, Touch Me”) and all the glam decadence your steamy loins can stand as Tim Curry makes the entire galaxy wet on “Sweet Transvestite.” There’s even a faux dance craze that turned out to be, get this, an actual global sensation. (We’re looking at you, Time Warp.) It’s a compilation, nay a simmering cauldron, of familiar sounds, classic themes and juvenilia spiked with some elusive ingredient that empowers even the meekest among us to slip on a wobbly pair of pumps and declare ourselves the baddest bitch in space—or at least the biggest hotdog in the castle. —Matt Melis

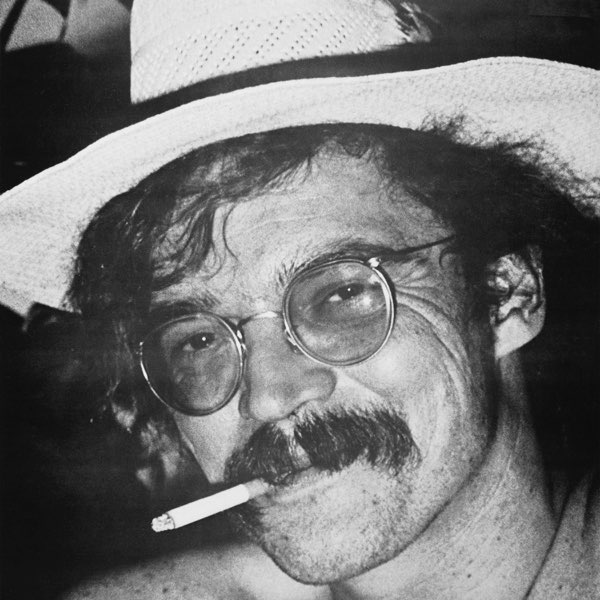

29. Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention: One Size Fits All

The 14th Mothers of Invention album (and 12th Frank Zappa album) is an all-time meeting of the whacko minds. Seriously, listening to these songs is like frying your brain without drugs. Zappa and his collaborators opted to ditch the suite-minded, symphonic structures of their previous work together by dispersing short, witty tracks in-between the more meandering compositions. The balance works because “Inca Roads” and “Can’t Afford No Shoes” play off each other, just as “Sofa No. 1” dissolves brightly into “Po-Jama People.” But One Size Fits All’s side two is 20 minutes well-spent, thanks to “San Ber’dino” and “Andy,” two 6-minute, gonzo riffs on prog-rock. This is Zappa at his best in the ‘70s—a tall compliment, considering he, the Mothers of Invention, and Captain Beefheart released the also-great Bongo Fury live album just four months later. —Matt Mitchell

The 14th Mothers of Invention album (and 12th Frank Zappa album) is an all-time meeting of the whacko minds. Seriously, listening to these songs is like frying your brain without drugs. Zappa and his collaborators opted to ditch the suite-minded, symphonic structures of their previous work together by dispersing short, witty tracks in-between the more meandering compositions. The balance works because “Inca Roads” and “Can’t Afford No Shoes” play off each other, just as “Sofa No. 1” dissolves brightly into “Po-Jama People.” But One Size Fits All’s side two is 20 minutes well-spent, thanks to “San Ber’dino” and “Andy,” two 6-minute, gonzo riffs on prog-rock. This is Zappa at his best in the ‘70s—a tall compliment, considering he, the Mothers of Invention, and Captain Beefheart released the also-great Bongo Fury live album just four months later. —Matt Mitchell

28. Brian Eno: Another Green World

Brian Eno’s third solo album is the bridge between his rock beginnings and his ambient trailblazing. On Another Green World, Eno builds warm textures through organ and piano, synthesizers and noise generators, early drum machines, Robert Fripp’s extraterrestrial guitar leads, and even a couple of drum performances by Phil Collins. It’s definitely more minimal than his first two LPs, but it’s far from Music from Airports; there’s still singing on five of its 14 songs, most notably on the beautiful (and oft-covered) pop song “St. Elmo’s Fire” and the swaying trot of “I’ll Come Running,” and instrumentals like “The Big Ship” and “Sombre Reptiles” explore rhythms, melodies, and emotions in structures not too far removed from more conventional pop music. It’s clearly a transitional work that combines the best of Eno’s early era with some of the techniques and ambitions that would come to define him; the songs with vocals are more abstract and experimental than what he accomplished on Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain, and you can hear the seeds of Eno’s later work throughout. All in all it’s a foundational classic from a weird era when the mainstream rock world and major labels still had a bit of room for groundbreaking experimentalists. —Garrett Martin

Brian Eno’s third solo album is the bridge between his rock beginnings and his ambient trailblazing. On Another Green World, Eno builds warm textures through organ and piano, synthesizers and noise generators, early drum machines, Robert Fripp’s extraterrestrial guitar leads, and even a couple of drum performances by Phil Collins. It’s definitely more minimal than his first two LPs, but it’s far from Music from Airports; there’s still singing on five of its 14 songs, most notably on the beautiful (and oft-covered) pop song “St. Elmo’s Fire” and the swaying trot of “I’ll Come Running,” and instrumentals like “The Big Ship” and “Sombre Reptiles” explore rhythms, melodies, and emotions in structures not too far removed from more conventional pop music. It’s clearly a transitional work that combines the best of Eno’s early era with some of the techniques and ambitions that would come to define him; the songs with vocals are more abstract and experimental than what he accomplished on Here Come the Warm Jets and Taking Tiger Mountain, and you can hear the seeds of Eno’s later work throughout. All in all it’s a foundational classic from a weird era when the mainstream rock world and major labels still had a bit of room for groundbreaking experimentalists. —Garrett Martin

27. Hako Yamasaki: Tobimasu

Hako Yamasaki was 18 years old when she made Tobimasu, but her writing has always been wise beyond number. The plucked overcast of “Bōkyō” is Yamasaki’s sentimental introduction where she podiums her drama and aches into memory. “Let’s go back to that house,” she sings, “if only that house existed now.” Her vocals vibrate across palettes of jazz, woodsy pop, and nebulous folk. After the piano-and-bass waltz of “Sasurai,” Hiromi Yasuda strikes an acoustic guitar solo during “Kazaguruma.” Yamasaki’s lyrics are utterly poetic yet plainspoken: “I want to be alone today, everyone, please go somewhere.” Tobimasu is brilliantly arranged, its sequence even more unbelievably wise. The epic and breathy “Kage Ga Mienai” is six minutes of transportive, deeply emotional songcraft; the title track’s melancholy touches into softness. Strings vibrate and her voice grows: “Now, I am leaving on a journey towards the one and only sky. I am beginning to fly.” What a talented musician Yamasaki was from the very beginning. —Matt Mitchell

Hako Yamasaki was 18 years old when she made Tobimasu, but her writing has always been wise beyond number. The plucked overcast of “Bōkyō” is Yamasaki’s sentimental introduction where she podiums her drama and aches into memory. “Let’s go back to that house,” she sings, “if only that house existed now.” Her vocals vibrate across palettes of jazz, woodsy pop, and nebulous folk. After the piano-and-bass waltz of “Sasurai,” Hiromi Yasuda strikes an acoustic guitar solo during “Kazaguruma.” Yamasaki’s lyrics are utterly poetic yet plainspoken: “I want to be alone today, everyone, please go somewhere.” Tobimasu is brilliantly arranged, its sequence even more unbelievably wise. The epic and breathy “Kage Ga Mienai” is six minutes of transportive, deeply emotional songcraft; the title track’s melancholy touches into softness. Strings vibrate and her voice grows: “Now, I am leaving on a journey towards the one and only sky. I am beginning to fly.” What a talented musician Yamasaki was from the very beginning. —Matt Mitchell

26. Fleetwood Mac: Fleetwood Mac

It took Fleetwood Mac 10 tries to make a great album, and all they had to do was slap their full name on the front of it again, seven years after doing it the first time (when Peter Green ran the show). There are moments on Fleetwood Mac that make Rumours look underwhelming, namely Lindsey Buckingham’s chirpy “Monday Morning” and Christine McVie’s greatest effort, the sophisticated trance of “Over My Head” (which was the lead single, a correct choice). But then there is also “Rhiannon.” And “Say You Love Me.” And “Landslide,” a song still making folks ugly weep. At every turn, Fleetwood Mac gets greater. Even the lesser chapters, like “World Turning” and “Crystal,” aren’t skips. The band was well into its career by the time Fleetwood Mac arrived but, thanks to the young additions of American musicians (and lovers) Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, the LP may as well have been considered their debut. And nearly 10 million people bought into it. The band, strictly English for the better part of a decade prior, became incredibly SoCal and ushered the mythologized Laurel Canyon sound into its last overture before the commercial pop of the ‘80s washed it clean out of the mainstream. —Matt Mitchell

It took Fleetwood Mac 10 tries to make a great album, and all they had to do was slap their full name on the front of it again, seven years after doing it the first time (when Peter Green ran the show). There are moments on Fleetwood Mac that make Rumours look underwhelming, namely Lindsey Buckingham’s chirpy “Monday Morning” and Christine McVie’s greatest effort, the sophisticated trance of “Over My Head” (which was the lead single, a correct choice). But then there is also “Rhiannon.” And “Say You Love Me.” And “Landslide,” a song still making folks ugly weep. At every turn, Fleetwood Mac gets greater. Even the lesser chapters, like “World Turning” and “Crystal,” aren’t skips. The band was well into its career by the time Fleetwood Mac arrived but, thanks to the young additions of American musicians (and lovers) Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, the LP may as well have been considered their debut. And nearly 10 million people bought into it. The band, strictly English for the better part of a decade prior, became incredibly SoCal and ushered the mythologized Laurel Canyon sound into its last overture before the commercial pop of the ‘80s washed it clean out of the mainstream. —Matt Mitchell

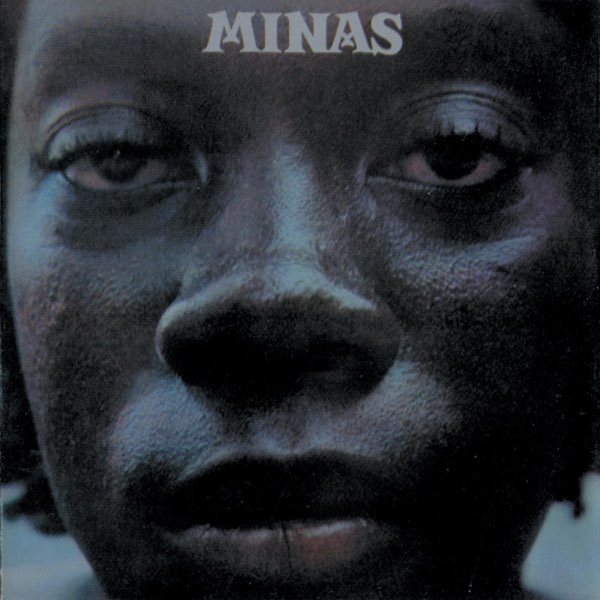

25. Gilberto Gil & Jorge Ben: Gil e Jorge (Ogum Xangô)

It is rare to hear two of the finest Brazilian musicians come together for a samba masterpiece, but that is what Jorge Ben and Gilberto Gil did in 1975 when they made Gil e Jorge. There’s an argument to be made that this is Gil’s best work, and it’s certainly one of Ben’s strongest performances. The two guitarists were each other’s greatest compliment, as Gil’s spiritual bombast fell right into place in the company of Ben’s soulful balance. Gil e Jorge is a loose, improvisational flow of energy—four men’s bodies remembering the music from within. Voices pitch up like repiniques while Djalma Corrȇa’s bateria and Wagner Dias’ rhythms anchor every song’s jubilance. “Quem Mandou (Pé na Estrada)” may remind Western listeners of the Diamonds’ “Little Darlin’,” while “Taj Mahal” is a guitar revolution packed into 14 minutes. There’s something profoundly courageous in music like this, for how it gestures toward freedom without abandon. Gil and Ben push each other closer to perfection, coming out on the other side with one of the greatest MPB albums of all time. —Matt Mitchell

It is rare to hear two of the finest Brazilian musicians come together for a samba masterpiece, but that is what Jorge Ben and Gilberto Gil did in 1975 when they made Gil e Jorge. There’s an argument to be made that this is Gil’s best work, and it’s certainly one of Ben’s strongest performances. The two guitarists were each other’s greatest compliment, as Gil’s spiritual bombast fell right into place in the company of Ben’s soulful balance. Gil e Jorge is a loose, improvisational flow of energy—four men’s bodies remembering the music from within. Voices pitch up like repiniques while Djalma Corrȇa’s bateria and Wagner Dias’ rhythms anchor every song’s jubilance. “Quem Mandou (Pé na Estrada)” may remind Western listeners of the Diamonds’ “Little Darlin’,” while “Taj Mahal” is a guitar revolution packed into 14 minutes. There’s something profoundly courageous in music like this, for how it gestures toward freedom without abandon. Gil and Ben push each other closer to perfection, coming out on the other side with one of the greatest MPB albums of all time. —Matt Mitchell

24. The Band: Northern Lights-Southern Cross

After a run of disappointing releases, the Band reunited with Bob Dylan in 1974 and served as his backing band on Planet Waves and a tour that led to the oft-lauded live album Before the Flood, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson ditched Big Pink for Shangri-La in Malibu, where they’d make the career-resurrecting Northern Lights – Southern Cross in 1975, their first LP of original material in half-a-decade, all of which was composed by Robertson alone. Thanks to “Acadian Driftwood,” “It Makes No Difference,” and “Jupiter Hollow,” Northern Lights was an ambitious pivot by the Band, as Hudson turned to using synthesizers, but it also was, by most accounts, a commercial failure. It was a goodbye caught on 24-track tape. It’s sugary but tragic, warmed by the nearby Pacific Ocean yet hurt by the fivesome’s nearing finale. There is so much music to be heard, and I feel lucky that the Band made a record like Northern Lights – Southern Cross. Few acts ever get to begin, but the Band got to begin twice. —Matt Mitchell

After a run of disappointing releases, the Band reunited with Bob Dylan in 1974 and served as his backing band on Planet Waves and a tour that led to the oft-lauded live album Before the Flood, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson ditched Big Pink for Shangri-La in Malibu, where they’d make the career-resurrecting Northern Lights – Southern Cross in 1975, their first LP of original material in half-a-decade, all of which was composed by Robertson alone. Thanks to “Acadian Driftwood,” “It Makes No Difference,” and “Jupiter Hollow,” Northern Lights was an ambitious pivot by the Band, as Hudson turned to using synthesizers, but it also was, by most accounts, a commercial failure. It was a goodbye caught on 24-track tape. It’s sugary but tragic, warmed by the nearby Pacific Ocean yet hurt by the fivesome’s nearing finale. There is so much music to be heard, and I feel lucky that the Band made a record like Northern Lights – Southern Cross. Few acts ever get to begin, but the Band got to begin twice. —Matt Mitchell

23. Led Zeppelin: Physical Graffiti

Led Zeppelin’s sixth album is unequivocally their best, and potentially the greatest double-album ever. Physical Graffiti runs a massive 82 minutes in length and commands every bit of your attention. If Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, John Bonham, and John Paul Jones reached the mountaintop on IV, then Physical Graffiti is them lighting the entire peak on fire. Side two may very well be one of the greatest three-song runs in all of rock and roll, as the stretch from “Houses of the Holy” through “Kashmir” is so singular that you couldn’t imagine the record getting better after that—and then the band performs “In the Light,” “Bron-Yr-Aur,” “Down by the Seaside,” and “Ten Years Gone” in a row on side three. The quality of Physical Graffiti is maddening, if only because few rock bands have ever lit such a pronounced match of badassery in such a small vacuum. The album is brutal, symphonic, dense and, at the end of the day, a tour de force of brilliance. Not many records made after 1975 sound this good. —Matt Mitchell

Led Zeppelin’s sixth album is unequivocally their best, and potentially the greatest double-album ever. Physical Graffiti runs a massive 82 minutes in length and commands every bit of your attention. If Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, John Bonham, and John Paul Jones reached the mountaintop on IV, then Physical Graffiti is them lighting the entire peak on fire. Side two may very well be one of the greatest three-song runs in all of rock and roll, as the stretch from “Houses of the Holy” through “Kashmir” is so singular that you couldn’t imagine the record getting better after that—and then the band performs “In the Light,” “Bron-Yr-Aur,” “Down by the Seaside,” and “Ten Years Gone” in a row on side three. The quality of Physical Graffiti is maddening, if only because few rock bands have ever lit such a pronounced match of badassery in such a small vacuum. The album is brutal, symphonic, dense and, at the end of the day, a tour de force of brilliance. Not many records made after 1975 sound this good. —Matt Mitchell

22. Guy Clark: Old No. 1

Until his mid-30s, Guy Clark was a Houston boy playing a part in the city’s folk music movement. But when he and his wife Susanna moved to Nashville at the dawn of the ‘70s, Clark, who’d mentored the likes of Steve Earle and Rodney Crowell, went into RCA Studio B and recorded his debut album, Old No. 1. Simply put, it’s the greatest country debut of all time, thanks to tracks like “Texas – 1947” and “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” both of which usher in the record’s melancholic side two. But three minutes into Old No. 1 lies Clark’s magnum opus: “L.A. Freeway.” In the melody rings a Southern orchestra, thanks to Johnny Gimble’s fiddle and Mickey Raphael’s harmonica. Crowell and Earle join Emmylou Harris, Sammi Smith, Gary B. White, Lea Jane Berinati, and Florence Warner for backing harmonies, sending Clark on his way like a crowd hollering on the sides of a parade. “Love’s a gift that’s surely handmade,” he sings to Susanna. “We got somethin’ to believe in, don’t you think it’s time we’re leavin’?” —Matt Mitchell

Until his mid-30s, Guy Clark was a Houston boy playing a part in the city’s folk music movement. But when he and his wife Susanna moved to Nashville at the dawn of the ‘70s, Clark, who’d mentored the likes of Steve Earle and Rodney Crowell, went into RCA Studio B and recorded his debut album, Old No. 1. Simply put, it’s the greatest country debut of all time, thanks to tracks like “Texas – 1947” and “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” both of which usher in the record’s melancholic side two. But three minutes into Old No. 1 lies Clark’s magnum opus: “L.A. Freeway.” In the melody rings a Southern orchestra, thanks to Johnny Gimble’s fiddle and Mickey Raphael’s harmonica. Crowell and Earle join Emmylou Harris, Sammi Smith, Gary B. White, Lea Jane Berinati, and Florence Warner for backing harmonies, sending Clark on his way like a crowd hollering on the sides of a parade. “Love’s a gift that’s surely handmade,” he sings to Susanna. “We got somethin’ to believe in, don’t you think it’s time we’re leavin’?” —Matt Mitchell

21. Pink Floyd: Wish You Were Here

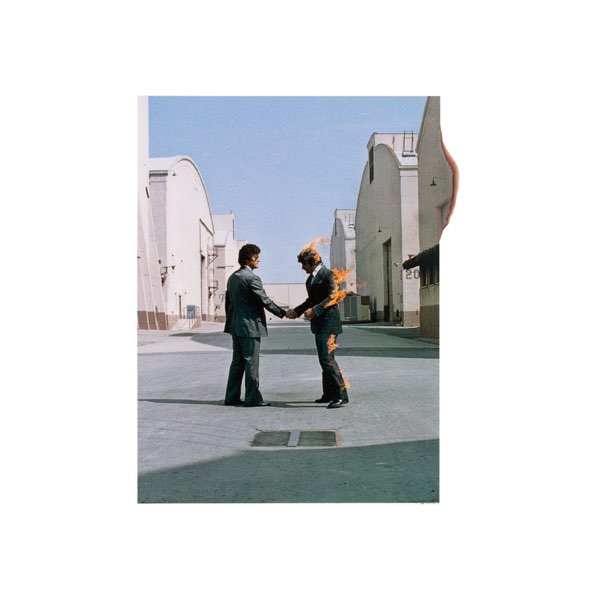

Worthy of its praise for the longevity and limitless perfection of the title track alone, Wish You Were Here is the dense, damning love letter to Syd Barrett that the rest of Pink Floyd took seven years to write and record after the frontman’s departure. So few tributes in rock and roll have ever been so generous, and the scope of Wish You Were Here reaches much farther than that—as the band tackles alienation and music criticism in ways that were much more complex than anything they’d ever written about before. The centerpiece of the record is the nine-part “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” which was cut in half and positioned as the opening track on side one and the closing track on side two. “You were caught in the crossfire of childhood and stardom, blown on the steel breeze. Come on, your target for faraway laughter. Come on you stranger, you legend, you martyr, and shine! You reached for the secret too soon, you cried for the moon” is, maybe (definitely), the greatest lyrical sequence in the band’s entire history, as Waters honors Barrett in such an empathetic and celebratory way, you’d think the estranged bandleader had been on 10 Pink Floyd records before then and not just one-and-a-half. Wish You Were Here stands the test of time because it dared to defy time itself—yet it’s so grounded in realism and familiarity that it floats just above us always. —Matt Mitchell

Worthy of its praise for the longevity and limitless perfection of the title track alone, Wish You Were Here is the dense, damning love letter to Syd Barrett that the rest of Pink Floyd took seven years to write and record after the frontman’s departure. So few tributes in rock and roll have ever been so generous, and the scope of Wish You Were Here reaches much farther than that—as the band tackles alienation and music criticism in ways that were much more complex than anything they’d ever written about before. The centerpiece of the record is the nine-part “Shine On You Crazy Diamond,” which was cut in half and positioned as the opening track on side one and the closing track on side two. “You were caught in the crossfire of childhood and stardom, blown on the steel breeze. Come on, your target for faraway laughter. Come on you stranger, you legend, you martyr, and shine! You reached for the secret too soon, you cried for the moon” is, maybe (definitely), the greatest lyrical sequence in the band’s entire history, as Waters honors Barrett in such an empathetic and celebratory way, you’d think the estranged bandleader had been on 10 Pink Floyd records before then and not just one-and-a-half. Wish You Were Here stands the test of time because it dared to defy time itself—yet it’s so grounded in realism and familiarity that it floats just above us always. —Matt Mitchell

20. Tony Bennett & Bill Evans: The Tony Bennett / Bill Evans Album

Recorded in a Berkeley studio over four days in June 1975, Tony Bennett and Bill Evans’ collaborative album is a document of two musicians, at the peak of their respective powers, exceptionally falling into one another. Bennett, who’d been making uptempo, rock-tinged pop records during the decade’s first half, was without a record contract yet Evans, ever the maestro of European classicism, pulled fine drama out of the singer. There are no bells and whistles present, no overproduction or funny attitudes—just Bennett’s room-clearing croon and Evans’ idiosyncratic piano playing. Performing standards—like Bernstein’s “Some Other Time,” Ray Noble’s “The Touch of Your Lips,” and Mancini/Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses”—this record could pass as a happy accident, as peers riffing on the songbooks in their back pockets. But that would be a misinterpretation of just how great this music is, how their talents rarely contrast. The work is simple yet definitive—a paintbrush dragging picture-perfect techniques across the margins of deeply personal interpretations. For 35 minutes, Bennett and Evans speak a language no one else can. —Matt Mitchell

Recorded in a Berkeley studio over four days in June 1975, Tony Bennett and Bill Evans’ collaborative album is a document of two musicians, at the peak of their respective powers, exceptionally falling into one another. Bennett, who’d been making uptempo, rock-tinged pop records during the decade’s first half, was without a record contract yet Evans, ever the maestro of European classicism, pulled fine drama out of the singer. There are no bells and whistles present, no overproduction or funny attitudes—just Bennett’s room-clearing croon and Evans’ idiosyncratic piano playing. Performing standards—like Bernstein’s “Some Other Time,” Ray Noble’s “The Touch of Your Lips,” and Mancini/Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses”—this record could pass as a happy accident, as peers riffing on the songbooks in their back pockets. But that would be a misinterpretation of just how great this music is, how their talents rarely contrast. The work is simple yet definitive—a paintbrush dragging picture-perfect techniques across the margins of deeply personal interpretations. For 35 minutes, Bennett and Evans speak a language no one else can. —Matt Mitchell

19. Terry Allen: Juarez

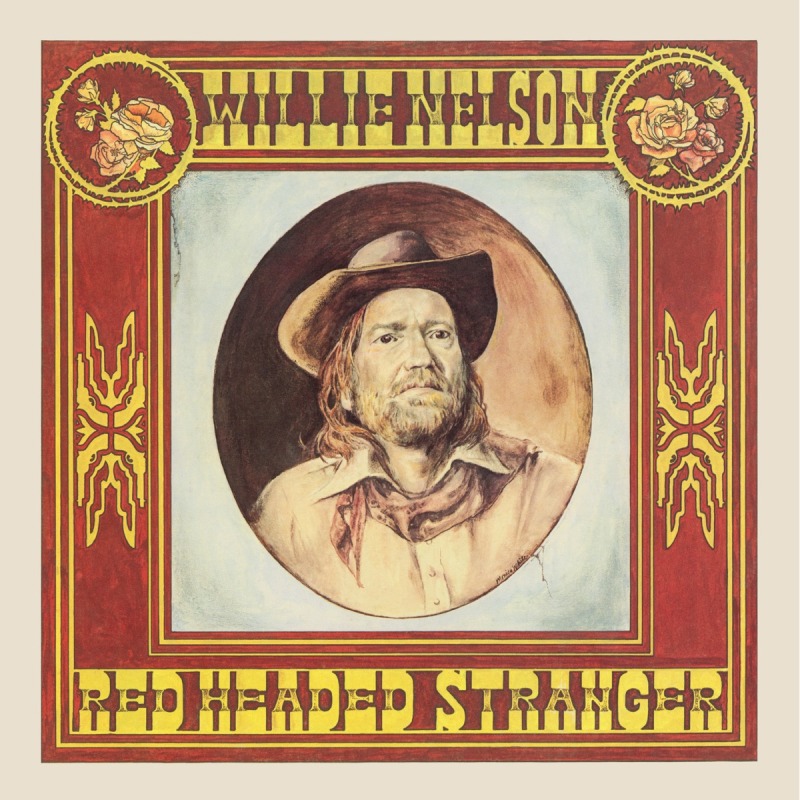

Terry Allen was 32 years old when he made his debut album, Juarez, a song cycle about the Aztecs, cheap sex, and gun-toting at the Rio Grande border. In 1975, fellow Texan Willie Nelson wrote up a song cycle of his own, the oft-lauded (and rightfully so) Red Headed Stranger, but I find myself returning to Allen’s piano portrait of Western, “Texican badman” redolence more as I grow older. He’s channeling John Prine more than Waylon Jennings, and there’s a spritz of Randy Newman in the cynicism, too. And the way he breaks into the stories, like a narrator delivering necessary, scene-splitting exposition, is reliably theatric but never exhausting. The leaving Los Angeles song “Cortez Sail” is especially profound with cinematic vignettes: “See how the lightning makes cracks in your air, tearing the clouds then closin’ the tear,” Allen sings out. “Yeah, but you’re not surprised anymore. You’re going home to Paradise.” Elsewhere, images of pachuco queens, TV glows in-between toes, skinny bodies slipping like knives into perfume, anal with whipped cream, a captain drunk with a “Gypsy bitch,” and border girls with body curls litter the outlaw’s highway on “Border Palace,” “What of Alicia,” “The Run South,” and “Four Corners.” There are corny measures on Juarez, but much of Allen’s writing depends on the humorous, vulgar truths of humanity at-large. “I scribbled down some of the mysteries and I stopped that howling wind,” he sings on “Writing on Rocks Across the U.S.A.” The characters of Juarez are as in love as they are enigmatic. Today’s rainbow certainly is tomorrow’s tamale. —Matt Mitchell

Terry Allen was 32 years old when he made his debut album, Juarez, a song cycle about the Aztecs, cheap sex, and gun-toting at the Rio Grande border. In 1975, fellow Texan Willie Nelson wrote up a song cycle of his own, the oft-lauded (and rightfully so) Red Headed Stranger, but I find myself returning to Allen’s piano portrait of Western, “Texican badman” redolence more as I grow older. He’s channeling John Prine more than Waylon Jennings, and there’s a spritz of Randy Newman in the cynicism, too. And the way he breaks into the stories, like a narrator delivering necessary, scene-splitting exposition, is reliably theatric but never exhausting. The leaving Los Angeles song “Cortez Sail” is especially profound with cinematic vignettes: “See how the lightning makes cracks in your air, tearing the clouds then closin’ the tear,” Allen sings out. “Yeah, but you’re not surprised anymore. You’re going home to Paradise.” Elsewhere, images of pachuco queens, TV glows in-between toes, skinny bodies slipping like knives into perfume, anal with whipped cream, a captain drunk with a “Gypsy bitch,” and border girls with body curls litter the outlaw’s highway on “Border Palace,” “What of Alicia,” “The Run South,” and “Four Corners.” There are corny measures on Juarez, but much of Allen’s writing depends on the humorous, vulgar truths of humanity at-large. “I scribbled down some of the mysteries and I stopped that howling wind,” he sings on “Writing on Rocks Across the U.S.A.” The characters of Juarez are as in love as they are enigmatic. Today’s rainbow certainly is tomorrow’s tamale. —Matt Mitchell

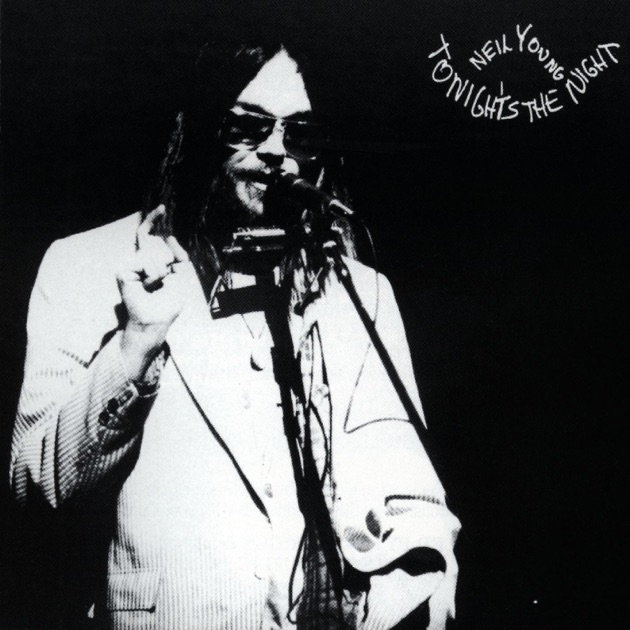

18. Neil Young: Tonight’s the Night

I don’t remember when I discovered Tonight’s the Night, nor do I remember how listening to it for the first time made me feel. I’m sure I was put off by its deliberately jagged instrumentation and Young’s heightened, piercing, nasally vocals. When I began to use his work as a vessel for my own closure with deaths that have lingered with me for years, I found “Tired Eyes” and “Mellow My Mind” and “Speakin’ Out”—songs that had the space to hold all of the suffering I couldn’t spare to carry anymore. And after getting shelved for two years after it was written and recorded, Tonight’s the Night got released in 1975 and was, immediately, unlike anything else Young had ever made up until that point. Fans understand it to be a record heavily influenced by the deaths of two men, roadie Bruce Berry and guitarist Danny Whitten. Nils Lofgren calls the album a “wake for all our heroes and friends that started dying.” The layout of Tonight’s the Night was extraordinary, because Young and David Briggs wanted it to be an “anti-production record” where the focus became, in modern terms, an exercise in following vibes. For casual fans of Young’s work, Tonight’s the Night arrives much rawer and looser than anything else he’d made up until that point. And that was the intention from the jump. —Matt Mitchell

I don’t remember when I discovered Tonight’s the Night, nor do I remember how listening to it for the first time made me feel. I’m sure I was put off by its deliberately jagged instrumentation and Young’s heightened, piercing, nasally vocals. When I began to use his work as a vessel for my own closure with deaths that have lingered with me for years, I found “Tired Eyes” and “Mellow My Mind” and “Speakin’ Out”—songs that had the space to hold all of the suffering I couldn’t spare to carry anymore. And after getting shelved for two years after it was written and recorded, Tonight’s the Night got released in 1975 and was, immediately, unlike anything else Young had ever made up until that point. Fans understand it to be a record heavily influenced by the deaths of two men, roadie Bruce Berry and guitarist Danny Whitten. Nils Lofgren calls the album a “wake for all our heroes and friends that started dying.” The layout of Tonight’s the Night was extraordinary, because Young and David Briggs wanted it to be an “anti-production record” where the focus became, in modern terms, an exercise in following vibes. For casual fans of Young’s work, Tonight’s the Night arrives much rawer and looser than anything else he’d made up until that point. And that was the intention from the jump. —Matt Mitchell

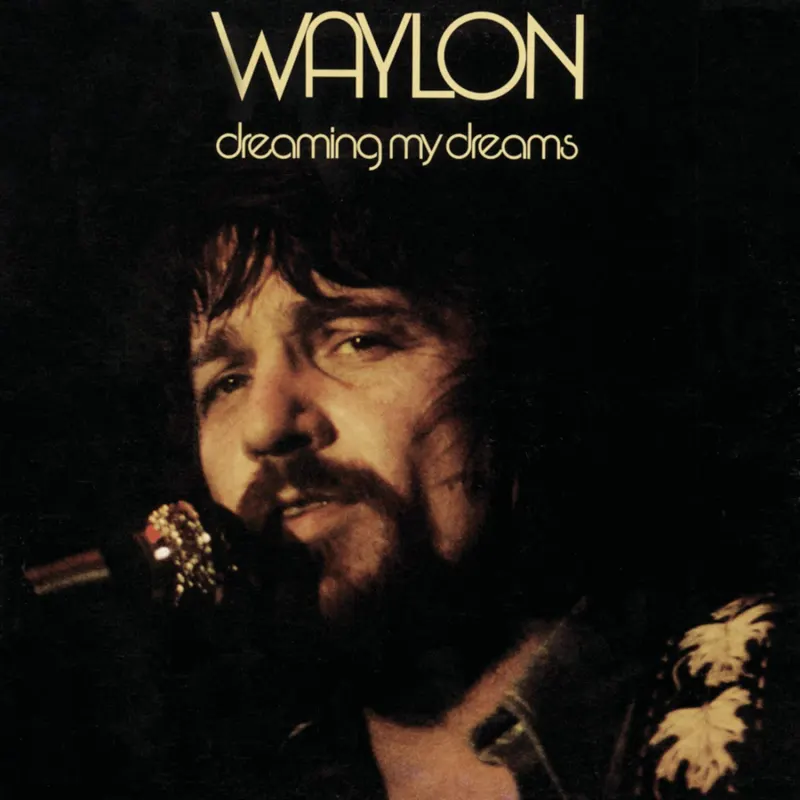

17. Waylon Jennings: Dreaming My Dreams

Even as a badass outlaw country star, Waylon Jennings could still bring the romance—and he proved as much with his 1975 LP, Dreaming My Dreams. Already 22 albums into his career, Dreaming My Dreams was the first record of Jennings’ to hit #1. He brought the swooning adoration in his love songs and tributes to his country music forefathers, like Hank Williams, Roger Miller, and Bob Wills, while making biting commentary on the genre. It’s emotional, sentimental and captivating, all while maintaining that rugged edge that made the Texan cowboy so lovable in the first place. —Olivia Abercrombie

Even as a badass outlaw country star, Waylon Jennings could still bring the romance—and he proved as much with his 1975 LP, Dreaming My Dreams. Already 22 albums into his career, Dreaming My Dreams was the first record of Jennings’ to hit #1. He brought the swooning adoration in his love songs and tributes to his country music forefathers, like Hank Williams, Roger Miller, and Bob Wills, while making biting commentary on the genre. It’s emotional, sentimental and captivating, all while maintaining that rugged edge that made the Texan cowboy so lovable in the first place. —Olivia Abercrombie

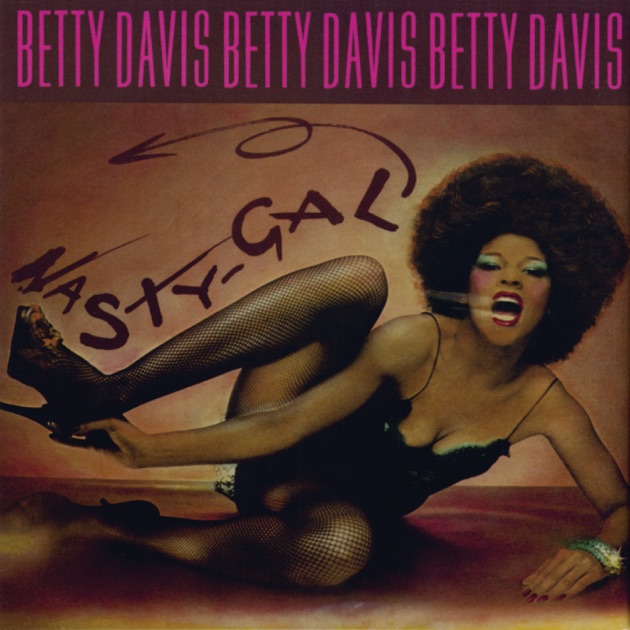

16. Betty Davis: Nasty Gal

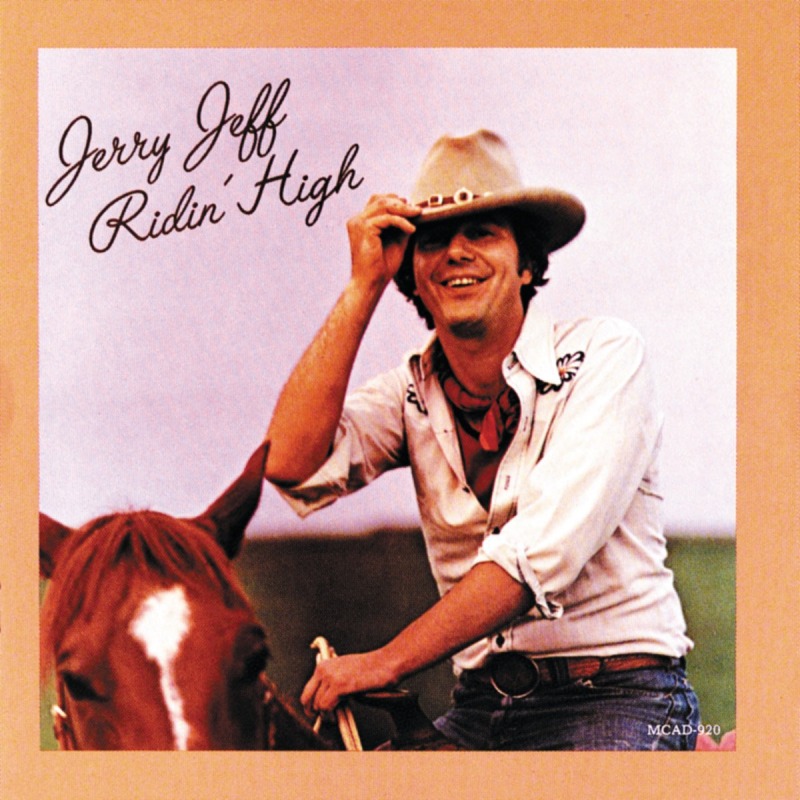

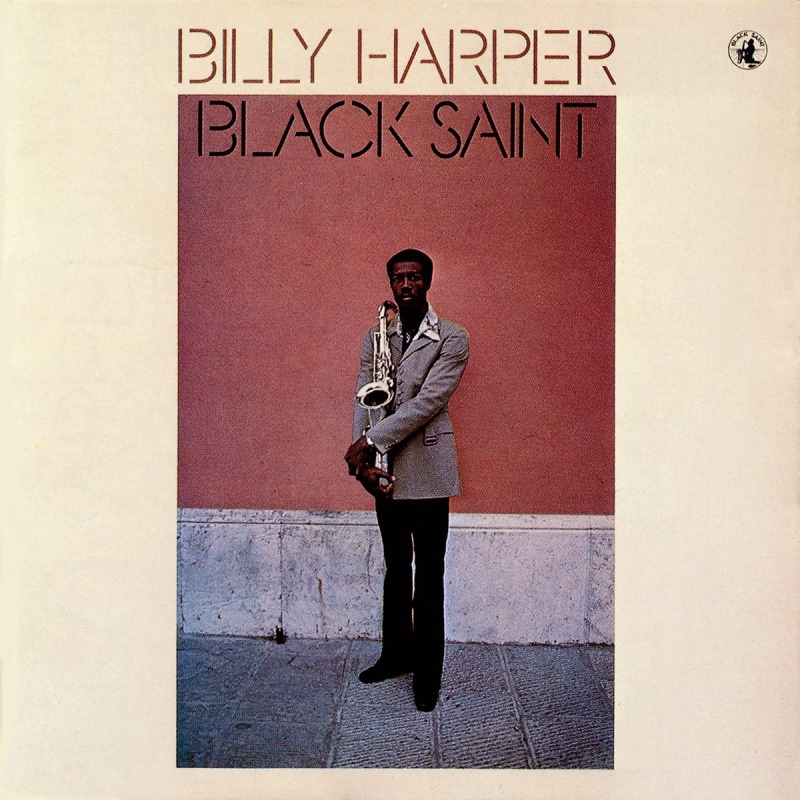

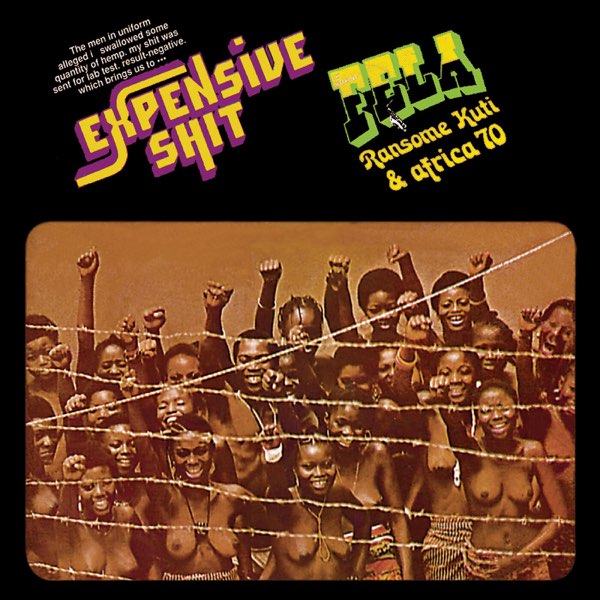

Betty Davis self-produced her all-time great 1974 album They Say I’m Different, but its follow-up, Nasty Gal, was a commercial failure upon arrival—a blow so devastating that Island Records canned Davis’ next record, Is It Love or Desire?, for more than 30 years. Critics weren’t high on Davis’ third album either, but retrospect has allowed for the listening world to properly catch up. The legacy that often follows Davis is that she was ahead of her time, and Nasty Gal certainly is a primitive release for funk music. But these 10 songs aren’t about risks, they’re about Davis mastering her space-age, soul-deep getup and grooves. On “Talkin Trash,” Carlos Morales’ riffs scorch the earth, while Gil Evans’ arrangement on “You and I,” which Betty co-wrote with her ex-husband Miles Davis, is an outlier ballad that illustrates just how capricious her sound could be. “Getting Kicked Off, Havin Fun” turns into a funhouse mirror with Larry Johnson’s gnarly bass notes, while the on-the-nose, body-punishing “F.U.N.K.” name-drops Stevie Wonder, Tina Turner, Al Green, Anne Peebles, Barry White, Jimi Hendrix, Aretha Franklin, Chaka Khan, and others, presenting itself like a museum of Black art: “I was born with it, I will die with it, because it’s in my blood and I can’t get enough.” Nasty Gal is psychedelic and, as the title concurs, plain nasty in the heaviest, coolest sense. It rarely conforms yet displays a great balance of sexuality, agency, and gentleness. —Matt Mitchell