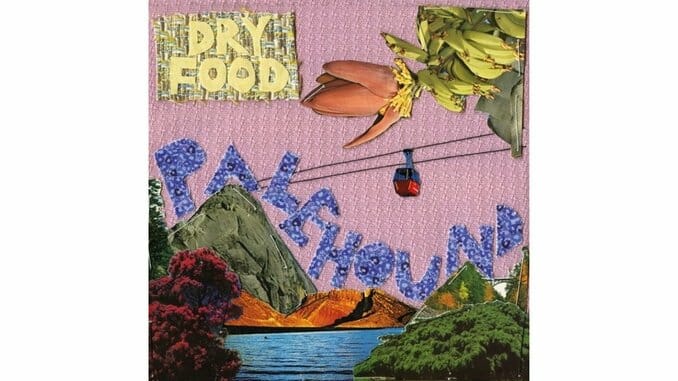

Palehound: Dry Food

Since breaking out with 2013’s endearing single “Pet Carrot,” Ellen Kempner’s guitar work has remained mostly hidden behind the hype that her band Palehound is the “next Speedy Ortiz,” or that her songwriting is influenced by The Breeders and Pavement. On Palehound’s debut full-length, Dry Food, you only need to listen to the tack “Cinnamon” to know this classically trained guitar player isn’t simply another ‘90s-sounding pastiche of torn jeans and flannel shirts.

21-year-old Kempner’s guitar prowess is Palehound’s staff of light, a six-stringed burning ember that guides you through her fractured song structures and doleful take on coming-of-age, the basis of Dry Food, an eight-song exploration of Kempner’s mental inner space during the period of 2013 and ‘14. Complex dynamics keep the album’s tracks from blending together into a giant collage, like the colorful travel magazine cutouts that create the cover art. The only constants are Kempner’s guitar and whispering vocals, which draw you into her dark world on tracks like “Molly,” where her counter-melody guitar riff gets attacked by fuzzed-out power chords. Kempner’s soft vocals puncture the heart with earnestness on tracks like “Dry Food” and create distance with the reverb-soaked “Cinnamon,” where her voice interweaves masterfully with gently strummed guitar chords. In that sense, Palehound belongs more in the vein of rockers like Mac DeMarco and King Krule—sans the MAD Magazine-antics.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-