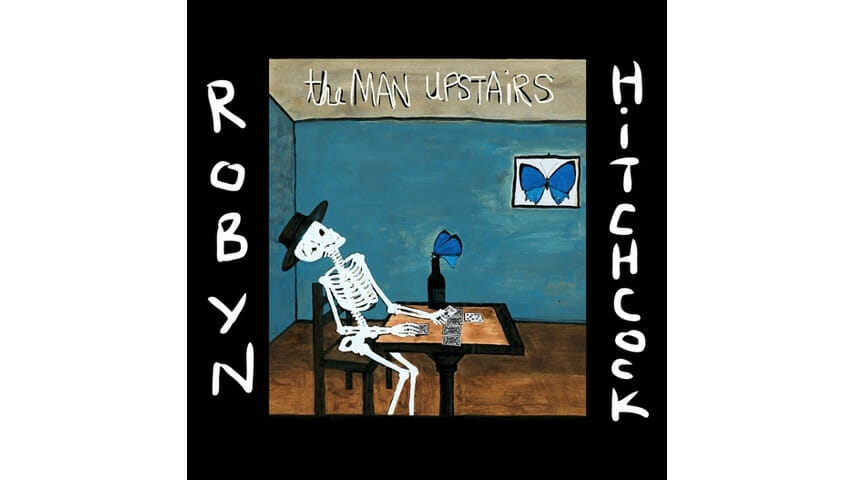

Robyn Hitchcock: The Man Upstairs

So many of Robyn Hitchcock’s songs owe their greatness to his wit and worldview.

Over 35 years—first with the Soft Boys and then with the Egyptians, Venus 3 and solo—Hitchcock carved out his niche as a songwriter: clever, surreal, imaginative and poignant. So when his 20th solo album was announced as a folk record, mixing covers (both well-known and obscure) with a few originals, the first question became how Hitchcock’s singular artistic voice would show itself in the project.

The title The Man Upstairs suggests that this record comes from a side of Hitchcock that’s always been there but is seldom seen. Hanging around, alongside his genius songwriting, is the voice of an enthusiastic yet reverent interpreter, one with a sharp sense of what songs to choose and how best to transform them.

Hitchcock’s most formative influences have been starkly clear in past projects—the 2002 Robyn Sings album of Bob Dylan covers and a 2006 Soft Boys reunion concert performance of Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd songs. But there’s nothing so cut-and-dried on The Man Upstairs. Instead, the covers are chosen out of a vault of personal favorites (and, as he says in Yep Roc’s press release, “songs I wished I’d written”) collected over the years.

The album starts with “The Ghost In You,” the 1984 Psychedelic Furs hit, and immediately Hitchcock’s skill as a recontextualist takes over. Instead of the romantic bounce of new wave synths, Hitchcock strums an acoustic guitar through the chords, with cello and piano coloring the edges. It’s an approach that puts a direct emphasis on the lyrics, and suddenly it’s clear why Hitchcock is drawn to the song. With lines like “angels fall like rain” and “stars come down in you,” the lyrics inhabit the same exaltedly strange realm as many of his own songs.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-