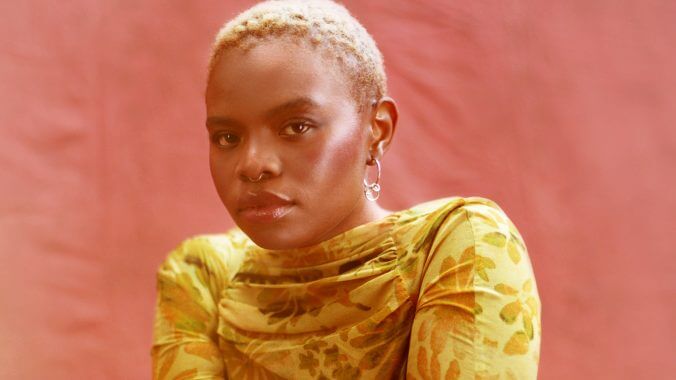

COVER STORY | How Vagabon Built Her Fantasy

Singer/songwriter Laetitia Tamko talks working with Rostam, pulling euphoria from the torture of loss and her latest album, Sorry I Haven’t Called

Photo by Tonje Thilesen

Laetitia Tamko doesn’t want to talk about the sad stuff, she just wants to talk her shit. That’s how her latest record, Sorry I Haven’t Called, begins. “I’m way too high for this, riding on a wave too low,” she sings. “Never found myself through the smoke, but I can’t resist. I’m ready to leave with you, I’ve been getting way too bold.” It’s obvious that Tamko’s orbit—which she encircles under the moniker Vagabon—is now built with a newfound agency, where she can open up and be vulnerable with the audience she’s long cultivated.

While some artists are keen on sketching out the bones of a record, Tamko makes songs until she’s making an album—it’s rarely ever an exercise or endeavor that includes any conscious decision to see an entire project’s scope before any of it is written. “I’m just gathering ideas, trying to figure out what it is that I’m gonna say,” she explains. “In a conversation I was having with one of my friends, she was like, ‘It sounds like you keep talking about wanting to speak freely.’” Upon that back and forth, Tamko pulled out the attitude that would follow her across Sorry I Haven’t Called. It was an act of confidence, of finesse, of boldness; when she finished the sublime dance track “Can I Talk My Shit?,” it became immediately apparent that it was destined to be the first song on the album. It was her chance to let everyone know what they would be walking into for the next 30 minutes.

“I’ve always been really reserved in what I’ve decided to share, I’m a pretty private kind of person,” Tamko says. “My previous work has always reflected that, to me. I don’t know if it’s apparent to others but, to me, it’s always been like, ‘Oh, how can I talk about this in a way that doesn’t make me feel too exposed or too subjected to criticism or, even, feedback?’ How can I just be like, ‘I’m really just talking about me. It’s just me, it’s just me—don’t say anything’? The world expanded a bit, where it was like, ‘I don’t really care to be so beholden to those things.”

The Cameroon-born, New York-based singer/songwriter has made primitive alt-rock and electronica for as long as I’ve been cognizant of what exists and thrives just beyond the genres’ forefronts. During the pandemic, I don’t know if there was a record that meant more to me than Vagabon, Tamko’s self-titled sophomore effort that saw her turn away from romanticizing the ways in which she’d been hurt, brutalized. She was once an underground artist clawing at the surface, attempting to—as a Black woman making guitar-oriented music—break into an indie rock scene that had (and still has) a serious visibility problem for Black folks, especially Black femme and non-binary artists. When Tamko did a 180-degree turn from her debut album Infinite Worlds and re-defined what intimacy meant in the context of her sound and grandeur, it became apparent that her bold, bright and limitless approach to songwriting would endure—and it made the rest of us eager to know where she would turn next, whenever that time was meant to come.

But I remember when, six years ago, I saw Tamko play a set in Columbus, Ohio on one of the hottest summer nights I can remember. She was the opening act at a gig at Park Street Saloon—a local venue lost to redevelopment only a few months after the show concluded—and it was just her and her guitar, with NNAMDÏ on the drum kit. The two musicians played many of the tracks from her debut, a reflective, sparse and minimalist rock record as emotionally dense as it is sonically bare-bones. Whenever Tamko talks about access around music, she always references Infinite Worlds.

“That album is really a product of my environment, being in the underground scene in New York and we couldn’t hear ourselves, the monitors never worked—so we played louder and we screamed into the microphone,” she says. “All of our friends, we were all self-taught, figuring out how to play those instruments. [Infinite Worlds] has this inherent kind of learning quality to it. I do think, even for me, it’s a bit jarring—it’s crazy to think that that wasn’t as long as the work seems like it should have been. It was just two albums ago. But it was like when you’re trying out different clothes—like, ‘Oh, my God, am I goth? Am I steampunk? Where do I feel good?’ All of those elements are still a part of me.”

Tamko is right. A guitar-focused, brutally vulnerable song like “Anti-Fuck” would have landed nicely on the Infinite Worlds tracklist, while the four on the floor-style of something like “You Know How” would have paired nicely on a record with the fluid, disco ethos of “Water Me Down.” For Tamko—and the world of Vagabon as an artistic vessel, as a means to a curious end—the work of the last half-decade has been a gradual, but exponential, forward-motion towards how she can push herself and make the most progress, creatively and emotionally, before even sharing it with everyone else.

While Sorry I Haven’t Called is, at its core, a dance record, Tamko’s relationship with her guitar hasn’t wavered. Her parents bought her her first six-string from Costco and, while many folks are first drawn to the piano and that becomes their entry point into the kaleidoscopic wonders of music-making, Tamko found comfort and affection in folk music—but she’s quick to insist that she was strictly into the not-cool version of it, because her only access to the contemporary sonic world was through radio. Rather than discovering Elliott Smith or Nick Drake, she was taking notes from Coldplay and Taylor Swift. Her brother was into System of a Down, which propelled her into an affinity for Slipknot. All of this is just to say, for Tamko and for the origins of Vagabon, there was not a piano in sight—which makes her turn towards (and full embrace of) synthesizers all the more flooring.

The way Tamko uses guitar now is more so on a sample basis. The first dozen seconds of “Do Your Worst” platform a voice memo of the song’s demo—of her playing acoustic guitar—put through a tape machine and modulated. The instrument has evolved from just being a songwriting tool for Tamko; now, it’s a fixture of her overall sound design, a building block to an even more visceral world, glazed with affect and stretched into a new shape. To unspool Tamko’s music is a bountiful reward. Especially on Sorry I Haven’t Called, the work is dazzling and stirring.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-