Neil Breen: B Movie Supreme Being

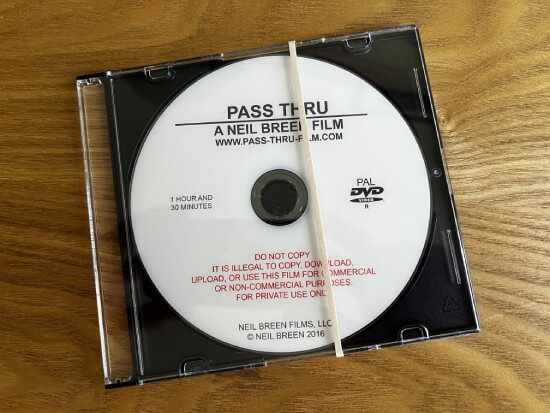

Photo by Neil Breen Films, LLC

The world of “bad movies” has many deities, from Ed Wood to Tommy Wiseau. But none have the numen artistry, the lunatic integrity or the sheer incorruptibility of Neil Breen, a 64-year-old auteur with no formal filmmaking experience and a galaxy brain swimming with delirious ideas.

There’s a scene in his latest epic, Cade: The Tortured Crossing, in which his character is attacked by a white tiger. The sequence, which sees a sexagenarian quasi-superhero and a janky 3D tiger model engage in a 90-second Greco-Roman knuckle lock until they come to some sort of mutual understanding, is not an anomaly. It is vintage Breen.

The director landed on Earth in 2005 with his debut feature, Double Down. Shot around the scrublands of his native Nevada, it’s a cyberthriller in which he plays a genius hacker tasked with shutting down the Las Vegas strip to cleanse the city of sin. The film set a few important precedents. First, its non-specific, pseudo-spiritual libertarian rhetoric would become the thematic throughline of Breen’s sci-fi dramas, which feature AI, aliens, ghosts, gang violence and casual genocide as an answer to government corruption. Second, it established that Breen doesn’t simply make “bad movies.” He makes egosploitation movies.

The term “egosploitation” describes films that are written, produced and directed by the same person, who typically casts himself as the hero, usually some sort of supersoldier or messiah figure. Breen’s characters are often both. Five years after playing an altruistic and highly decorated government merc in Double Down, Breen gave himself a promotion: to god. In his 2010 sophomore feature, I Am Here…. Now, he plays an all-powerful being so disappointed by humanity that he turns up on Earth to wipe out anyone who doesn’t meet his moral standards.

As with all egosploitation filmmakers, from John De Hart to Frank D’Angelo, Breen shows little sign of self-awareness. For every one of his scenes that might mean something, there are 10 more that betray his fundamental misgivings about how the world—and everything in it, from syringes to oxygen masks to windows—actually works, leaving many first-time viewers wondering whether he’s really a deep-cover agent for Adult Swim. Is this guy really for real? Good question.

Details about Breen’s past are scarce. Prior to making films full-time, Breen says he was a practicing architect working on large commercial buildings. Fans have searched for proof of that. Instead, what they found was an expired real-estate license, leading some to speculate that he was never an architect but in fact an estate agent with delusions of grandeur. Breen says otherwise. The few things we know for certain are that he lives in Las Vegas, loves supercars and has an AOL email address.

Released in 2015, Breen’s third feature was a turning point. Fateful Findings was as close to a breakout film as an inexperienced middle-aged egomaniac could possibly make. His star exploded, especially on YouTube, with the likes of RedLetterMedia and Kurtis Conner publishing watchalongs and reaction videos that have collectively racked up tens of millions of views.

“It was pretty apparent that he was special from very early in the film,” Adam Johnston, known for his channel YMS, tells Paste. “Then I started piecing together that it wasn’t just Fateful Findings but a body of work and that there were consistencies within his films. That’s when I decided to marathon all of his available movies. No matter how far we go, it seems like he’s still producing consistently entertaining and admirable content.”

Breen is aware of his “bad movie” fanbase and claims to embrace his cult status. But he’s clearly skeptical of it too. In 2019, he contacted the admins of the Facebook fan group Real Human Breens and demanded that the page be shut down for “impersonating” him. He’s quick to call out illegal sales and streams of his films. Like his movies, his actions seem to disclose his anti-governmental anxieties around dishonesty, liberty and identity theft.

Those who’ve had the pleasure of meeting Breen in person say he’s a nice, normal, level-headed dude. In audience Q&As, he makes self-deprecating jokes, is open about his growth and learnings as an artist, and showcases more self-awareness than you’d expect from a man who frequently casts himself as a supreme being. That is, until the topic turns to cinema.

Few filmmakers have ever seemed less indebted to the history of the pictures. In fact, it’s almost as if Neil Breen has never seen a movie in his life. Not only because his work is so strangely orchestrated, but also because of his refusal to remark on his influences.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-