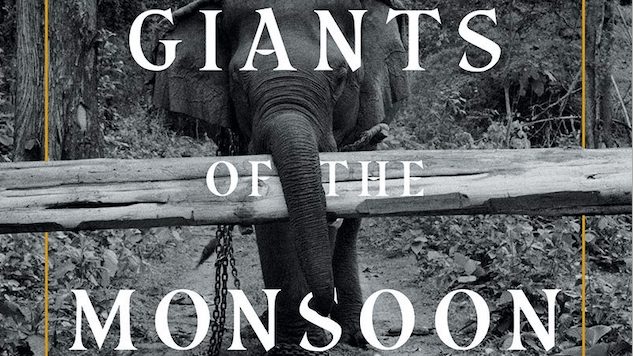

Jacob Shell’s New Book Reveals That Giving Elephants Jobs Could Ensure Their Survival

The symbiotic relationship between the elephant riders, called mahouts, of Southeast Asia and their gargantuan mounts is colored with compassion and, at times, cruelty. As geographer Jacob Shell’s Giants of the Monsoon Forest makes clear, it could also be the best chance of survival for both the Asian elephant and the people who ride upon their broad backs.

Asian elephants’ immense strength—the trunk alone capable of cracking a person like glow stick—and intellect has made them irresistible to humanity for centuries. Just look at the martial pachyderms of the Indian ruler Porus, scattering Alexander the Great’s armies as so many ashes. But beyond the terror of war elephants lies a more gentle—though still dangerous—working relationship, one which continues to this day. Asian elephants’ strength and dexterity, in combination with their deep understanding of human commands and complicated problems, make them invaluable for teak logging.

The wet forests of Myanmar become impassable quagmires after the monsoon drenches them, their thick mud devouring any motorized vehicle. Elephants move easily across this terrain, hauling and lifting valuable logs. When those same storms juice rivers into raging monsters and the bridges are swept away, the elephants serve as ferries, carrying passengers and goods across the dangerous waters.

The wet forests of Myanmar become impassable quagmires after the monsoon drenches them, their thick mud devouring any motorized vehicle. Elephants move easily across this terrain, hauling and lifting valuable logs. When those same storms juice rivers into raging monsters and the bridges are swept away, the elephants serve as ferries, carrying passengers and goods across the dangerous waters.

These elephants live a unique life in animal-human relations. While food stock, farm animals and domesticated pets spend their entire lives living among people, the working Asian elephant is like an employee. The elephant completes its work during the day and is turned loose into the forest to find food and wild mates at night. Its speed is dampened by shackles, which can be broken if the elephant truly wants to run. In the morning, the elephant is found by its mahout—a task made more difficult if it has stuffed its wooden bell with leaves and mud to mute it. The mahout then bathes the elephant in a morning ritual before they begin the work day.

This relationship may sound undesirable or even detestable to those who wish to see Asian elephants living free. But as Shell’s book makes clear, it’s their role as laborers, rather than as tourist attractions, which may save the species. It’s a moral area as grey as the elephant’s flesh, but worth examining if the world’s endangered Asian elephant population is going to survive.

Ivory poaching is not the biggest problem facing Asian elephants; the loss of their lush jungle habitat is the more pressing threat. For many, the establishment of large nature preserves, where the jungle can remain untouched and the elephants unmolested, is the dream scenario. As Shell points out, however, such a dream can only be supported by tourism, and tourism can only be supported by infrastructure. The hotels, amenities and roads required to make nature preserves economical would mean, ironically, an increase in deforestation.

The kind of teak logging which uses the elephants, on the other hand, requires nature. Both animals and humans have a vested interesting in keeping the forests intact, and the nightly release of the elephants ensures genetic diversity and healthy populations. It is the great paradox of ecology that sometimes intervention is the answer, from the culling of deer and eradication of invasive species to the selling of hunting permits—elephants included—to pay for protecting the very same animals. Shell even imagines a world in which elephants could help victims of tsunamis and other natural disasters, thereby expanding their roles.

Throughout Giants of the Monsoon Forest, Shell hints at a captivating conclusion: Asian elephants, much like the first canines to cozy up to the fire, are utilizing their symbiotic relationship with people to help ensure their genetic survival. Despite the chains and danger, despite the cruel methods with which some—but not all—mahouts train them, a continued reliance on elephant labor may guarantee that they last.

It’s a controversial position to insist that some of these intervention methods may be the best for the animals, but time is quickly running out. By making Asian elephants an important part of the economy and appealing to the most powerful of human motivations, greed, these creatures may yet be saved.

B. David Zarley is a freelance journalist, essayist and book/art critic based in Chicago. His work has appeared in The Verge, The Atlantic, Quartz, Hazlitt, VICE Sports, Chicago Magazine, Sports Illustrated, New American Paintings, the Myrtle Beach Sun News and numerous other publications.