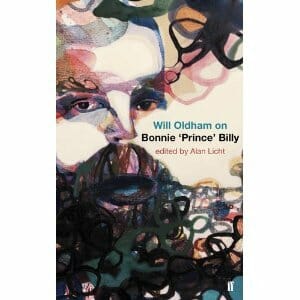

Will Oldham On Bonnie “Prince” Billy by Alan Licht

Prince Among Men

The new book Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy represents a rare approach to writing about music and the musicians who produce it: the book-length interview.

Alan Licht, a musician who has played guitar on numerous albums, written two books, and contributed to music publications like Wire, interviews Will Oldham, a musician (with whom Licht has collaborated) and an actor.

Oldham is better known these days as the singer, Bonnie “Prince” Billy.

Licht displays remarkable knowledge about the chronology and particulars of Oldham’s career, and Oldham happens to be a fascinating interviewee, willing to discuss his entire career and approach to art in great detail.

What’s the motivation behind this book? In his preface, Licht suggests two.

First, he tells us that the book’s subject has often been described as an “elusive, puzzling, and obfuscating artist who does not like to be interviewed.” So the book works to “provide a basic information source for future interlocutors.” (It’s also an excuse to avoid more of those damn interviews.)

Second, Licht claims that the book explores something unique and anomalous in pop music – Will Oldham, who “questions and usually outright rejects any and all accepted record industry wisdom with regard to virtually every aspect of . . . music. . . As much as, if not more than. . . Neil Young, Bob Dylan, or Lou Reed, Oldham is a law unto himself.”

Comparisons like that may not be of much use, but the book certainly goes a long way towards explicating Oldham’s idiosyncratic ideas about making and using music.

In the ‘80s, a young Will Oldham devoted his energy to acting – most famously in John Sayles’ Matewan – but he constantly hung around the music scene in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. In fact, when Licht first met his future interview subject, Oldham happened to be living in a house with a member of Pavement (one of the most influential indie bands of the ‘90s) and a member of then-defunct Louisville band Slint. (Slint’s 1991 release, Spiderland, carries a lot of weight in select circles).

Oldham started releasing his own music in 1992, and between that year and 1998, he put out a slew of albums and singles. He also changed the name on his recordings at least five times.

At the end of the ‘90s, Oldham – who continues to release music frequently, and sometimes to act as well – settled on a performing personality that he has more or less stuck with since: Bonnie “Prince” Billy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-