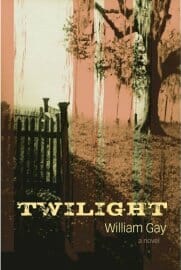

William Gay — Twilight

William Gay — Twilight

Prose master weaves chilling tale about an undertaker not doing his job

William Gay’s dark new novel, Twilight, will likely divide readers into two camps—those who love the Southern Gothic element and those who don’t.

The story is death-drenched, the characters hardly seem to belong to the last century, the language is torqued with rhetorical flourishes, and the plot is packed full of cruel and gruesome events that feel as if an entire culture were emptying the repressed contents of its gloomy psyche into the world. I found myself alternating between both camps, loving and resisting the book, reading it first as a brilliant fable, then as a nightmare, but also picking up a vibe that seemed to bring the novel very close to parody, a story mocking its own methods. Kenneth and Corrie Tyler discover that the undertaker in town, Fenton Breece, hasn’t properly buried their father, nor anyone else for that matter, filling the caskets with trash, leaving the dead undressed, removing their genitals. Kenneth steals Fenton’s briefcase and discovers a packet of pictures—corpses arranged in sexual poses, some of which include “Breece himself, nude and gross and grinning, capering gleefully among the painted dead.” Breece hires Granville Sutter, a known murderer and the embodiment of unreasoning evil, to get the pictures back.

The prose in Twilight makes extensive use of the Latinate so that as we move through this rustic, backwoods locale we get a world that is “malefic” and “implacable,” we get “stygian trees,” and things are “telluric” and “revenantial.” While this language elevates and dignifies the struggles of the overlooked, it also hits the page somewhat self-consciously, marking the novel’s terrain as “literary.” It argues the case for a certain worthiness, but, perhaps, after Faulkner and McCarthy, that worthiness isn’t quite so much in doubt, and as a result the heightened rhetorical language of Twilight might, to some readers, feel overly insistent.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-