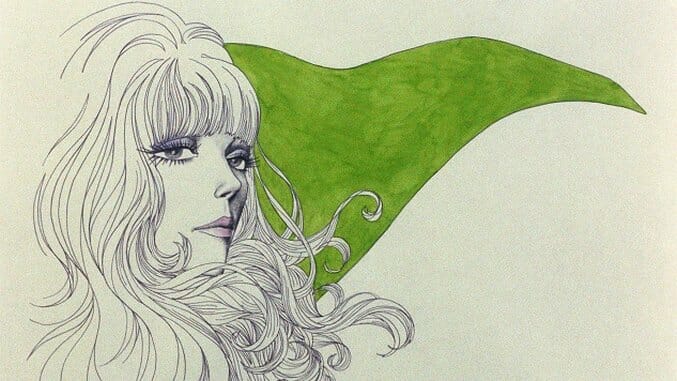

Belladonna of Sadness

Eiichi Yamamoto’s Belladonna of Sadness is not a learning film. It will not reveal new truths about the essence of your being that you were previously unaware of. It will not teach you anything about your fellow man or about the human condition. It will, however, give you an idea of what a psychedelic drug trip might look like, sans the hallucinatory experience in which your pants unbutton, slide off your legs, and neatly fold atop your dresser of their own volition. (It also lasts a scant 85 minutes.) The film can be reasonably described as a product of both its era, the 1970s, and its creator, the legendary co-parent of anime and manga alongside animator Osamu Tezuka. Whether that makes it less of a brain melt is another thing entirely.

Between 1969 and 1973, the pair collaborated on the Animerama series, a trio of animated films made with adult bents and focused on adult themes. Their efforts began with A Thousand and One Nights, continued with Cleopatra, and ended with Belladonna of Sadness, each of which can be variably categorized by single-word qualifiers that denote their existential statuses: “Lost,” “rare,” “unreleased.” The good news is that Belladonna of Sadness is lost no longer, having been restored and released for our viewing pleasure by the people at Cinelicious Pics. For any hardcore cinephile, the archaeological accomplishment alone is reason to seek out the film as it does the theatrical rounds in the United States. Its unbridled surreality is merely icing.

Except that it isn’t. It’s the phantasmagoric cake. When we talk about movies that must be seen to be believe, we are talking about movies like Belladonna of Sadness. The language of letters is ill-equipped for translating the film’s particulars, peculiarities and perplexities to a reading audience. It is simple enough to say that little of the movie is actually animated, as Yamamoto built his visual landscape on a collection of absolutely gorgeous still images that his cinematographer, Shigeru Yamazaki, carefully pans across, which lends those images a sense of movement even if they are static by their very nature. And yes, it’s easy to talk about Belladonna of Sadness’ color scheme, the mesmeric vibes of its free jazz soundtrack, its wanton use of phallic symbolism, or its fascination with Satan and witchcraft. But prattling on about those details does them very little justice on paper. Yamamoto’s vision is singularly bananas.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-