The 10 Best Documentaries of 2020 (So Far)

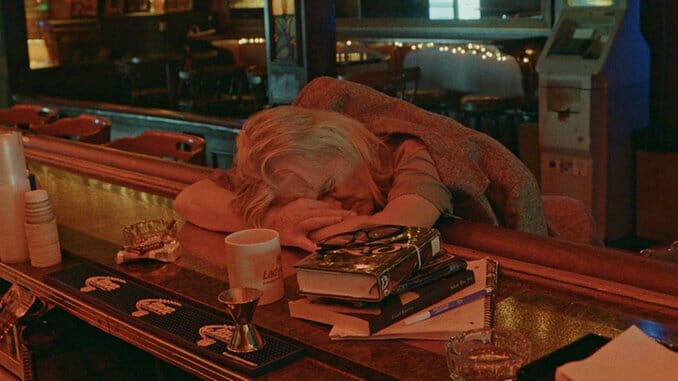

Image via True/False

Picking the best documentaries for this year so far has been a far more taxing endeavor than usual. Obviously: With the pandemic annihilating most distribution plans, documentary filmmakers are finding an especially harrowing landscape for their genre. Typically following up festival runs with long and drawn out waits before their movies are ever available outside of those circuits—hoping that someone like Netflix or Amazon swoops in to get the process moving; praying that a surprise Oscar nomination somehow makes audiences aware that the film even exists—documentarians are all the more dependent now on streaming opportunities. And in many cases, for many excellent films screened at TIFF or Sundance or True/False, those opportunities just aren’t coming.

So, to make a list of 10 films we could stand behind, we got a little creative: We’ve included one film originally “released” in 2018, but which has become only available through Mubi this year, meaning that most people won’t have seen it until now. We’ve included a film that might not get distribution, but has had some screenings in art house theaters pre-quarantine. We’ve refrained, too, from including films that are still struggling to find a home, like Khalik Allah’s IWOW: I Walk on Water, or that are dependent on specific context, and so aren’t really a 2020 film until the artist says so, like in the case of Zia Anger’s My First Film. Or we’ve just decided to include a film that hasn’t gotten much attention to give it some.

Regardless, much of this will get sorted out in the next six months or so. Until that happens, here are our picks for the 10 best documentaries of 2020 so far:

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets Release Date: January 24, 2020 (Sundance)

Release Date: January 24, 2020 (Sundance)

Directors: Turner Ross, Bill Ross IV

Rating: NR

Runtime: 98 minutes

Songs of the soul flow from the drunken mouths of the jukebox-loving inebriates in Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets. The Ross brothers have created a prototype barroom experience: It is closing night for the fictionalized Roaring 20’s in Las Vegas, a real bar actually operating in their home base of New Orleans, and the regulars, led by local professional actor Michael Martin and otherwise populated with true bar-frequenting non-actors, have come together to kiss their favorite watering hole goodbye. Its much-discussed fictional framework is merely that—a framework—beneath which legitimate human interactions play out, with characters representing themselves and actually drinking the night away. There is authentic war vet commiseration and romantic longing, bartender-led singalongs and, inevitably, one guy trying to fight another “with eyes tattooed on his eyelids.” The holy trinity of dive bar life—despondency, frivolity and pugnacity—is present and spiritually enriching.

As always, the Ross bros depict those before their camera with the deepest care and respect. Pangs of regret and anguish sound between moments of hilarious drunken crosstalk, with Martin’s character pulling in close his younger, rambunctious four-eyed friend and imploring him not to likewise spend his life in a bar. The film runs the gamut of drunken night emotions, from wistful dancing to maudlin bouts of self-loathing, but the mood is never pinned to any specific emotion; it is less about one peak or one valley than it is about creating the shape of a waveform in itself. Yet each crest and trough is tinged with the fleeting feeling of the other: To be low is to be touched by the immense depth of drunken feelings, and to be high is to ride forth in embarrassing obliviousness. But somehow the images never whiff exploitation; they radiate a sense of humanity and an understanding of these American outcasts, who will surely flit from one closing bar to the next. What awaits them thereafter is a mystery, and perhaps a sad story we do not need to know. —Daniel Christian

Where to Watch: Available widely on July 10th; some details available here

City So Real Release Date: March 5, 2020 (True/False Film Festival)

Release Date: March 5, 2020 (True/False Film Festival)

Director: Steve James

Rating: NR

Runtime: approx. 240 minutes

There is perhaps no film that exudes the collective essence of Steve James’s body of work as much as his latest. City So Real is ostensibly about a Chicago in crisis amid the trial of former Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke, who was charged with the first-degree murder of Laquan McDonald in 2018, and the crowded 2018-2019 mayoral election. The film’s most immediate charms do not come from navigating these threads, however. For all its outward perspective, it feels more than anything else a film in which James is expressing a very particular and complicated affection for his home city. In that way he synthesizes his finest films.

City So Real retains the sprawling intersectionality of America to Me but reduced to a tidy four hours, and at times echoes the place films of Frederick Wiseman, like Belfast, Maine or Monrovia, Indiana, in its commitment to documenting such a comprehensive array of people, spaces and conversations. James replaces Wiseman’s distance with closeness, using chance encounters with the likes of dog-walkers and Uber drivers to provide essential shading of this multifaceted city portrait. He makes excursions to seemingly every corner of Chicago, highlighted by a graphic that appears on screen to indicate which neighborhood this barbershop, or this dinner party, belongs to. As James weaves between these revealing vignettes and scenes of embedded access with several mayoral candidates, City So Real takes a sweeping look at the public and private lives of Chicago, of the political machine and of everyday sidewalk stories, of life at work and sometimes at home. Exploring racial and cultural contradictions that often lurk just below the surface, James’s camera seems to parse the dissonance and cacophony of city noise to locate each individual voice for a brief moment. Beneath the scaffolding of the election, these brief encounters amass to the point that the minutiae transcends itself. We see a collection of moments that speak to James’s understanding of humanity, often troubled, mundane and optimistic all at once. —Daniel Christian

Where to watch: Still on the festival circuit, and James is reportedly adding new footage, but you may be able to catch it through festival-based streaming engagements

The Grand Bizarre Release Date: 2018 (finally available in wide release)

Release Date: 2018 (finally available in wide release)

Director: Jodie Mack

Rating: NR

Runtime: 61 minutes

A spectacle of tedium; an opus of patience: Experimental filmmaker Jodie Mack seems to bring so many of her aesthetic and physical concerns to bear with the jaw-dropping The Grand Bizarre, one struggles to conceive of the ways she “got that” or “did that” or “made that happen.” Context, especially in Mack’s work, is important—the climax of the hour-long film uses the scant sounds of Mack’s 16mm Bolex camera in her studio, clicking once per image, to convey just how arduous the gleeful images we’d witnessed were to birth—and while we watch the swathes of textiles and colors spin and whirl across the screen and throughout countless international landscape, patterns whorling in time to a, in turns, quirky and menacing and blissful techno beat (like Holly Herndon’s Platform or Matthew Herbert’s concept albums, an arrangement of post-industrial detritus metamorphosing into music), we can’t escape the nagging question: Was all this work worth it? The answer must be “absolutely,” because The Grand Bizarre is too often astounding, but the answer is in the question as well. Mack wants us to know that she individually photographed innumerable pieces of cloth, that she painstakingly animated this whole hybridized doc. Mack wants us to be constantly aware of her work—just as she, in filming huge open air markets and major shipping ports and long car rides with fabric strobing in the rear view mirror (how many hours did she sit in the back of a car and just hold up pieces of cloth?), begs us to think about the labor behind these textiles and colors and patterns and materials, how much human effort is expelled in getting them, doing them, making them happen. Exciting and exhausting, The Grand Bizarre is both celebration and eulogy to that which nourishes us as much as it kills us. —Dom Sinacola

Where to watch: Now finally available for home viewing on Mubi

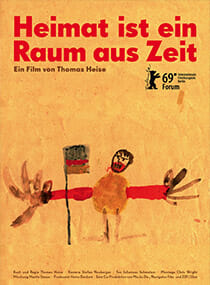

Heimat Is a Space in Time Release Date: September 2019 (TIFF)

Release Date: September 2019 (TIFF)

Director: Thomas Heise

Rating: NR

Runtime: 218 minutes

Sites of acknowledged historical significance—battlefields, museums or specific locations of importance—hardly seem to exist in the present tense; they live as cordoned-off spaces of reflection and contemplation, where a peaceful Now blankets a turbulent Then. Visitors who pass through know that the history that has happened in this space is so consequential it has caused time to stop, that nothing else can happen atop what has already taken place. The present cannot look forward. It must look back.

Thomas Heise’s Heimat Is a Space in Time, a three-and-a-half-hour first-person opus tracing his family’s march through the troubled course of 20th century German and Austrian history, takes on the very sort of sensation described above, itself an isolated space for reflection on the past and an individual’s power in a flawed society. Heise presents passions and tribulations of yesteryear matter-of-factly, as if they are evidence of a deterministic perspective suggesting, with ample evidence, that our lives and our choices are dictated by the systems that organize our societies. When Heise reads a correspondence between his mother, Rosemarie, and one of her first lovers, Udo—the couple separated by the East/West Berlin split—he presents their discussions dryly, as if he did not know either party. Heise emphasizes how these bureaucratic limitations exist ideologically and spatially, quite literally shaping the opportunities available to us: The world imposes rules at the whims of those in power, and suddenly people who were together are apart even while living in the same city. This is a history specific to Berlin, but Heimat also views this trajectory as universal, just another rise and fall and rise of governments and systems. Yet the personal stories of Heise’s family, who remained in East Germany under the German Democratic Republic, inform this entire perspective, and its toll on the individual is never far from sight. The film, then, works as its own cordoned-off historical site: a plane of reflection on a past composed of stories specific and broad. In Heimat Is a Space in Time, the imprint of the past is so dense and enduring that its spectral qualities drift beyond the battlefields, beyond the monuments, barracks and documents, to dissolve into daily life. —Daniel Christian

Where to watch: Now available for home viewing on Vimeo ($9.99 for a three-day rental), courtesy of Icarus Films and presented in partnership with Anthology Film Archives

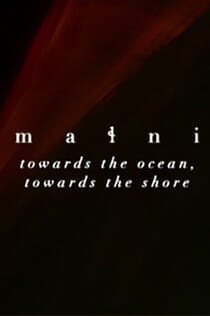

malni – towards the ocean, towards the shore Release Date: January 2020 (Sundance)

Release Date: January 2020 (Sundance)

Director: Sky Hopinka

Rating: NR

Runtime: 81 minutes

Sky Hopinka walks through spaces special and spurious in his first feature, malni – towards the ocean, towards the shore. The translation of the title lies within it, representing a liminal reality known well to both those who live in the Pacific Northwest now and those now who know of the death myth of the Chinookan people, those who lived in the Pacific Northwest first. In joining two Native locals, Jordan Mercier and Sweetwater Sahme, as they go about their rituals, daily and communal and otherwise, Hopinka grafts a sense of spiritual wonderment onto the warmly mundane stories they tell. Cultivating a lush soundscape, and seduced by long walks through the Columbia River Gorge or in and out of outcroppings rising by seemingly abandoned beaches on the Pacific—forward and backward through the membranes that separate sacred terrains—the film uses the death myth as a way to convey the power of the region, of especially the Portland area. Half an hour outside of the city either way wait things almost magical to behold; those of us who live here can feel ourselves change the more we cross urban lines. malni’s imbued with all that subtle transformation. —Dom Sinacola

Where to watch: Not yet available

The Metamorphosis of Birds Release Date: February 2020 (Berlinale)

Release Date: February 2020 (Berlinale)

Director: Catarina Vasconcelos

Rating: NR

Runtime: 101 minutes

Catarina Vasconcelos’s The Metamorphosis of Birds tells of three generations in her family, casting actors in softly stylized vignettes that begin with the director’s grandfather, then follow her and her father, past her mother’s death, to an unknown horizon. Steeped in symbolism that barely escapes pretentiousness—letters of romantic wishing; peacock feathers lined up and counted; household trinkets and the empty corners they once filled now replaced by decades of houseplant growth left unabated—but all the more precious for it, the film reveals the life of her grandfather, a naval officer gone for months and months at a time while his six children transformed at a distance, his wife left to raise them and navigate their change. Fathers are far away, but desperate to send their love, and mothers die, in many cases their deaths essential, somehow, to their little birds leaving the nest, to them forging new symbols out there, on their own. Vasconcelos becomes a character in her own film as she mourns the loss of her mother, but she’s interested, too, in tracing her grief through her father’s grief, losing both his wife and his mother, losing the house his mother kept for him and his many siblings, losing time to the vastness of the ocean that kept his father so far away. In the midst of such closeness to the artist, we too feel the overwhelming space between these loved ones, space that was never closed, space we’re encouraged to confront in our own lives. —Dom Sinacola

Where to watch: Not yet available, though it had some art house theater runs before quarantine

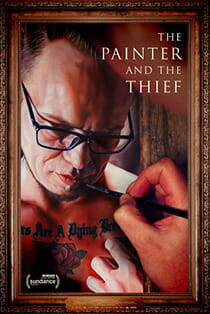

The Painter and the Thief Release Date: May 22, 2020

Release Date: May 22, 2020

Director: Benjamin Ree

Rating: NR

Runtime: 107 minutes

Career criminal and addict Karl-Bertil Nordland lays his eyes on the oil canvas portrait painted by his most recent victim, artist Barbora Kysilkova, 15 minutes into Benjamin Ree’s The Painter and the Thief, and then experiences a character arc’s worth of emotions in about as many seconds: shock, confusion, bewilderment, horror, awe, then finally gratitude communicated through tears. For the first time in his adult life, maybe in all his life, Nordland feels seen. It’s a stunning portrait, so vivid and detailed that Nordland looks like he’s about to saunter off the frame from his still life loll. Even a subject lacking his baggage would be just as gobsmacked as he is to look on Kysilkova’s work. In another movie, this one of a kind moment of vulnerability might’ve been the end. In The Painter and the Thief, it’s only the beginning of a moving odyssey through friendship, human connection and ultimate expressions of empathy. Ree’s filmmaking is a trust fall from a highrise. Trust is necessary for any documentary, but for Ree, it’s fundamental. The Painter and the Thief isn’t exactly “about” Nordland and Kysilkova the way most documentaries are “about” their subjects, in the sense that the film’s most dramatic reveals come as surprises to the viewer as much as to Nordland and Kysilkova themselves. The sentiment reads as cliché at a glance, but The Painter and the Thief argues that clichés exist for a reason. Think better of art’s power, Ree’s filmmaking tells us, but especially think better of each other, too. —Andy Crump

Where to watch: Available on Hulu

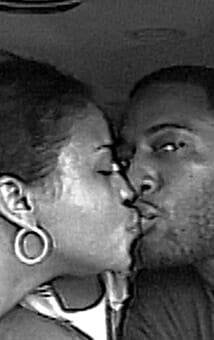

Time Release Date: January 25, 2020 (Sundance)

Release Date: January 25, 2020 (Sundance)

Director: Garrett Bradley

Rating: NR

Runtime: 81 minutes

Hope and despair constitute the vacillating emotions of Garrett Bradley’s Time, a lyrical look at Sibil “Fox” Rich’s efforts to free her husband from a Louisiana prison, where he is serving 60 years for a botched bank robbery, as his sons grow up without a father in the home (Fox herself served a few years for aiding in the crime). Her dogged attempts to break through to an uncaring bureaucracy are crushing in and of themselves, but the mannered composure with which she takes denial after denial builds a remarkable portrait of strength and resolution. One could ask how much Time grapples with the legitimate wrongdoing of the Rich parents, but Bradley does not give much credence to the question, because to do so would legitimize the system that, in doling out sentences so severe, ignores the humanity of the perpetrators in the first place. Sibil’s understanding of the morality of her and her husband’s situation is obvious, but also somewhat outside of the purview of Time, which is, for the better, much more concerned with the personal dynamic of the central relationship: how one sustains love and life when divided by an uncompromising and punishing system. The answer, in the case of the Riches, is Sibil’s home-made video diaries from a miniDV camera over the years, patched together with a score that gives the entire film the feel of a swelling epic—the intensely personal elevated to mythical proportions. Time truly builds to an ultimate moment of catharsis, which through its black and white imagery and heightened score fill an already deeply human moment with the additional powers of cinematic grace. —Daniel Christian

Where to watch: Not yet available, but Amazon will release in August

Vick Release Date: January 30, 2020 (ESPN)

Release Date: January 30, 2020 (ESPN)

Director: Stanley Nelson

Rating: NR

Runtime: 240 minutes

While The Last Dance generated more discussion than any other sports documentary this year—no doubt helped along by an early release meant to jolt the otherwise listless and mounting days of quarantine—it is Stanley Nelson’s portrait of Michael Vick’s rise-and-fall-and-plateau, Vick, that stands out as the most worthwhile resuscitation of legend in the first half of 2020. Part one of Vick, which plays in diptych fashion, allows us reminiscences of his revolutionary quarterbacking days with the Atlanta Falcons, when he was the world’s most popular football player: the singular awe that came from watching Vick so expertly navigate space and time, running circles around hapless opponents, weaving through defenses with such fluidity that he once caused two Minnesota Vikings to run into each other as if in a Looney Tunes sketch. Yet, every comment is spoken with the taste of regret, as Vick wonders what life would have looked like had he taken the advice of institutional mentors.

The second half is entirely dedicated to Vick’s dogfighting scandal, the aftermath and his successful comeback with the Philadelphia Eagles. Nelson doesn’t shy away from the atrocities of animal abuse, but perhaps gives Vick’s full story proper contextualization for the first time, looking at the history of dogfighting and Vick’s rough upbringing and cultural significance in Newport News, Virginia (he’s football’s analogue to Allen Iverson). As Tucker Carlson advocates a hanging, Steve Harvey wonders on stage where such righteous fervor was to be found after police killings of Black men, leading to a climax of “Man, fuck them dogs.” The film shows Vick as the perpetrator of an awful crime, but likewise finds space to humanize his Icarus story, portraying him asA homebody loyal to his roots who possessed such undeniable talent it swiftly lifted him from poverty to a world of extreme excess, where his every action as a flamboyant Black quarterback would be subjected to scrutiny and coded racism. The true story of Michael Vick, as Nelson shows, is that of someone caught in the maelstrom of expedited class mobility (e.g., ordering chicken fingers at his first steakhouse dinner with Falcons billionaire owner Arthur Blank), of changing expectations, of the choice between a corruptive relationship with day-one friends and a fortune reliant on cutting ties with his still-close past. A perception of self-preservation led to self-destruction, and eventually, whether one chooses to accept a redemptive arc or not, rebirth. —Daniel Christian

Where to watch: Available to stream (as part of the 30-for-30 series) on ESPN+

You Don’t Nomi Release Date: June 2019 (Tribeca Film Festival)

Release Date: June 2019 (Tribeca Film Festival)

Director: Jeffrey McHale

Rating: NR

Runtime: 92 minutes

For those of us culturally conscious during Showgirls’ release in 1995—who understood the inherently jarring nature of witnessing Jessie Spano rebuke her Valedictorian ways and succumb to the seedy world of adult exploitation—Jeffrey McHale’s witty and endlessly fascinating film essay, You Don’t Nomi, is a welcome codification of the film’s cult status. Loosely divided into sections addressing the film’s most notorious criticisms, as well as how it stands up to assessments as a misunderstood masterpiece and operates in conversation with Paul Verhoeven’s other films, McHale’s documentary eschews talking heads for voice overs from critics and programmers (David Schmader, Adam Nayman, Haley Mlotek), as well as the star of the Showgirls musical (April Kidwell), to wax both academically and emotionally about what the movie means to them. Some are obsessed, some disgusted; in some cases, McHale uses images to contradict the critics, often cuing up clips from Basic Instinct or Black Book or Elle or Verhoeven’s pre-Hollywood films to demonstrate that the issues he explores in Showgirls have never been far from his mind. Such is the fate of a film like Showgirls, one whose reputation (which McHale examines too) thrives on being considered in a vacuum, rather than as a piece of an auteur’s much broader oeuvre. As affectionately hyper-focused as he is on explication—on symbols and subtext and the director’s own (probably purposely) obtuse comments—and as much room as he gives to, in some ways, revitalizing and reconsidering Elizabeth Berkley’s performance as the titular and extremely weird Nomi, McHale never loses sight of that important context. Or that even more important love. —Dom Sinacola

Where to watch: Available to buy or rent on most major streaming platforms