In the fall of 2002, speaking to an audience of hundreds of university students, director Guy Ritchie did what anyone in his shoes would: Admitted to being in his flop era. “The idea was that the wife and I would make some sassy little art movie,” he explained, “but we got the shit kicked out of us.”

“The wife,” of course, was none other than pop icon Madonna, and their “sassy little art movie” was Swept Away, a remake of the 1974 Lina Wertmüller classic of the same name (technically, a somewhat longer one: Swept Away… by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August). What had originated as a $10 million passion project for the newlyweds was pronounced DOA in the weeks before Ritchie’s speech; in all, the film would only make about $1 million worldwide, and later became the biggest winner of the evening at the 2003 Razzies.

Ritchie’s Swept Away is indeed not great, defanging Wertmüller’s original story in the service of an uneven and unconvincing romantic drama proper, with many other baffling choices made along the way. But with two decades’ hindsight, it seems that coverage of the whole affair was probably overblown—caught up somewhat in early-2000s misogyny and existing cultural resentments of Madonna, who bore the brunt of the media ugliness even before the film’s release, but for whom a good shit-kicking was also par for the course. In that sense, it was Ritchie who’d have to navigate his first real professional initiation into his wife’s world.

Post-2002, there’s a risk of forgetting that Wertmüller’s Swept Away wasn’t itself universally loved. While yachting in the Mediterranean, the wealthy and insufferable Raffaella (Mariangela Melato) butts heads with Gennarino (Giancarlo Giannini), a communist working on the vessel. After a dinghy mishap leaves the two stranded on a desert island, their previous power dynamic is flipped: He’s calm and resourceful, easily procuring fish and water; she’s flailing and starving, continuing to verbally abuse him as if it’ll help her case. Eventually, using the promise of food and the threat of violence—the film is infamous in part for its near-rape scene—Gennarino nudges Raffaella into what the film terms a master-slave sexual relationship. Things have turned more traditionally passionate by the time they’re rescued, but, reunited with her money and social status, Raffaella reneges on her commitment to her sailor.

What some ‘70s viewers saw as biting satire registered for others as misguided—even dangerous. “Although Lina Wertmüller is a leftist, she is not, apparently, a feminist,” wrote Roger Ebert. “She seems to be trying to tell us…that woman is an essentially masochistic and submissive creature who likes nothing better than being swept off her feet by a strong and lustful male. This is a notion that feminists have spent the last 10 years trying to erase from our collective fantasies, and it must be unsettling…to find the foremost woman director making a whole movie out of it.” Swept Away was a ballsy candidate for a remake even before removing it three decades from its original context.

When production began on Ritchie’s version in 2001, the up-and-coming director had made just two features: 1998’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, which introduced Jason Statham to the world, and 2000’s Snatch, which nearly quadrupled the previous film’s gross. It was during those same years that Ritchie met, had a baby with and married Madonna, a much bigger celebrity and one a decade his senior—facts that tended to come up in mentions of the couple, whose younger half was at that point more of a tabloid staple than a celebrated filmmaker.

Sometime around the turn of the millennium, noted cinephile Madonna—for whom power plays, especially ones of a sexual nature, had long been an artistic preoccupation—showed Wertmüller’s Swept Away to Ritchie. “I remember seeing it years and years ago, and I always loved that film,” she’d later explain, “and Guy hadn’t seen it so he was curious.” In the months following their 2000 marriage, the two had been collaborating on short-form projects—the MTV-banned video for Madonna’s “What It Feels Like for a Girl” and the BMW-commissioned Star came out within months of each other—and found that they quite enjoyed working together. Naturally, there was talk of putting Madonna in a Ritchie feature.

“But Guy has a tendency to do very male, laddish…films,” she told Larry King. “So I always thought it would be some kind of quirky character.” Ritchie has said more recently that he was conscious of becoming typecast as the guy who made, well, Guy Ritchie movies: “My feeling was as though there’s a terrible danger to getting stuck in a particular genre as a filmmaker, so you’ve gotta be brave enough to jump out of your familiar territory.” A Swept Away remake was his solution, so he got to work on a new screenplay—writing it at lightning speed, according to his eventual commentary track. He began shooting it along the Mediterranean coast shortly after 9/11, and it was only weeks into production that Wertmüller officially granted him the rights, which she did in exchange for becoming a financial stakeholder. She’d gotten the idea to write and direct a sequel to her own film, and saw any renewed interest as useful to secure financiers.

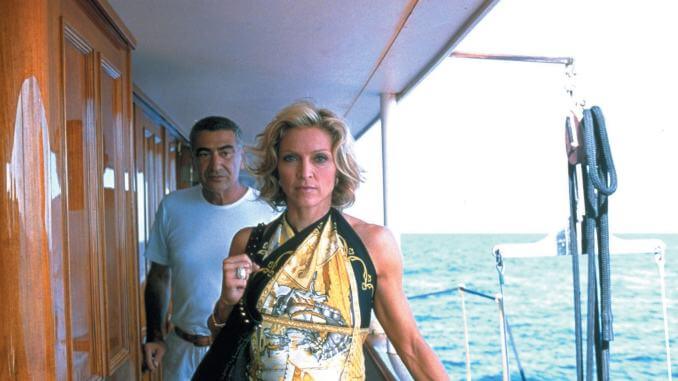

Long before the remake’s release, there was a sense that no one was exactly expecting a masterpiece. Aside from the riskiness of the source material, journalists pointed to Madonna’s mere handful of hits (and many more misses) on the big screen. But if expectations were already low, the final product didn’t manage to clear them. In Ritchie’s update, the yachters are American tourists rather than fellow Italians—already veering into something of an apples-and-oranges situation in terms of class analysis—and Raffaella is reimagined as Madonna’s Amber Leighton (which, weirdly, is also the name of Ritchie’s mother). Less radically, Gennarino is now Giuseppe, with Giancarlo Giannini’s son Adriano assuming his father’s original role. (The story goes that the younger Giannini simply responded to a casting call for Italian actors, and had already won the hearts of Ritchie and his team when they realized the connection.)

The newer story picks and chooses from the original seemingly at random—keeping the central class dynamic but nixing most of the capital-P politics, making the threat of sexual violence slightly less explicit but still having Amber slapped around on the island. “This rough trade Punch-and-Judy act didn’t play well [in 1974] and it plays worse now,” wrote Manohla Dargis. The remake also Hollywoodizes Wertmüller’s story: Italian characters speak to each other in accented English but also Italian; Mazzy Star and Goldfrapp play over montages; the ill-fated dinghy is destroyed not by shallow rocks but by Amber’s clumsiness with a flare gun. In an extended sequence, one of Madonna’s strongest and for obvious reasons, Giuseppe hallucinates Amber performing the Della Reese cover of “Come On-a My House.”

As for the rest of the film, Swept Away is by no means Madonna’s best work, but there’s also not much to wring from Ritchie’s dashed-out screenplay. On the yacht, Amber does little else but bark one-liners at everyone, and, in a running gag that isn’t terribly funny in practice—nor on paper—refers to Giuseppe (aka Pepe) as “Pee-pee.” One wonders whether her overacting is on some level a desire not to be confused for her character, a fellow gym rat accustomed to the high life.

Most notably, Ritchie abandons the original ending in favor of textbook romantic tragedy. Amber, having been character-developed by her island experience, chooses Giuseppe over her money, but their messages to each other are intercepted by her husband (Bruce Greenwood), leaving both halves of the couple thinking they’ve been rejected. The change was apparently Ritchie-spearheaded and not one that Madonna was necessarily on board with. “It’s clear that Madonna understands the original story better than Ritchie does,” wrote Ed Gonzalez of the rumor, “and the film’s ridiculous finale is a testament to their sad compromise.” In an interesting companion to his original review, Ebert echoed that sentiment: “This story was about something when Wertmüller directed it, but now it’s not about anything at all.”

Reviews were generally withering, with some critics asking whether the fiasco would end in divorce for the famous couple (no, or at least not for several years). Interviewed about its early American reception, Wertmüller called the situation a “disaster” for her sequel plans. (In the end, they’d never come to fruition.) A first for him in his career, Ritchie’s film was thereafter designated a straight-to-video release in the U.K. “It’s not being released [theatrically] here because people think it’s shit,” he said, though Madonna separately argued that “everyone in England has slagged it off without having seen it.” She added: “I enjoy acting…it’s fun. I don’t give a shit about what people say about it or my music…you can’t let it influence the choices you make.” While Ritchie’s 2002 would be defined by the flop, his “missus” (as he often referred to her publicly during their marriage) had only days—literally—before the conversation moved on to her divisive Bond song for, and heavily-panned cameo in, Die Another Day. Again, shit-kickings were very much a routine occurrence.

Interestingly, coverage of Swept Away tended to treat Mr. and Mrs. Ritchie as a sole authorial entity rather than a writer-director and his leading lady—who, yes, had played a role in shaping the remake. But if they were being viewed as jointly culpable, they weren’t critiqued evenly. Some reviews pointed to Ritchie’s lack of finesse. Most were overly concerned with Madonna’s body—phrases like “aerobicized to sinewy excess” and “a scary mix of pecs and peroxide” are common—and her “superior musculature” relative to Giannini’s was at one point implied to have made the scenes of physical violence less believable. Of her decision to play the role at all, even Dargis, whose review was more generous to the star than most, wrote, “Perhaps the idea of getting publicly smacked around seemed like a good way to curry favor with audiences that no longer hang on her every costume change.”

The idea of Madonna being a woman and artist past her prime (so to speak) was a common thread. It didn’t help that there was an age difference between Amber and Giuseppe that hadn’t existed between Raffaella and Gennarino, leaving journalists describing Amber’s character as an older woman in news segments. (Also hammering home the gap, Adriano Giannini told one interviewer, “It didn’t come easy for me to slap a woman, especially someone I had grown up listening to.”) But Ritchie’s screenplay also felt the need to address his wife’s age with a decidedly heavy-handed moment where Amber tells Giuseppe that he doesn’t have to “compete with 18-year-olds” the same way she does.

Once the dust had settled after the one-two punch of Swept Away and Die Another Day, Madonna vowed never to act in a film again, a promise she’s largely kept. Aside from killing the prospect of the Ritchies becoming a legendary filmmaking duo, the experience of 2002 seemed to push Madonna behind the camera; there, she could unleash her own meta-commentary as well as get the shit kicked out of her strictly for her own artistic vision. By the end of 2008, the same year she and Ritchie divorced, she’d made her feature debut with Filth and Wisdom, which riffed on her “struggling artist” origin story, and had already started work on what would become her second film, 2011’s W.E., about an American divorcée who upends the U.K. Neither was received particularly well, but that doesn’t appear to have dissuaded her from helming her own biopic.

Ritchie, for his part, eventually settled into what seems to be a comfortable groove, churning out an action-comedy every two or three years, some of them even pretty good. “There were a couple of issues there,” he said in 2017 of the Swept Away affair. “One was making it with my ex-wife, and two, making it on the back of my previous films…That was the first time I jumped out of my familiar territory, and boy, did I get punished for it.” It’s unclear what role he seems to think his own artistic capabilities played in the whole thing, but it’s true that his situation making his third feature had been unusual, not exactly allowing for all that much grace.

That Ritchie has since graduated from Madonna school has conceivably made his flop-sprinkled career a lot more manageable. As he said while promoting the critical and commercial misadventure that was 2017’s King Arthur: Legend of the Sword, sounding an awful lot like the ex-missus, “If someone gives you a load of money to go and make something and you have a lovely time doing it, at what point do you start to care about the judgment of your creation?”

Sydney Urbanek is a Toronto-based writer on movies, music videos, and things in between. She wrote her MA thesis on Jonas Åkerlund’s film and music video work. She also writes a newsletter called Mononym Mythology about mostly pop stars and their (visual) antics. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram.