The first thing one notices, looking at the horror genre as it exists on Max (formerly HBO Max), is that there’s an unusual level of genuine curation involved here. The overall scope of the service might not be quite as broad as something like Netflix, but you’re likely to have heard of far more of these films. That’s because unlike the horror selections of Netflix, Hulu or (especially) Amazon Prime, the bulk of the selections here aren’t made up of modern, straight-to-VOD, zero-budget productions with vague, one-word titles like Desolation or Satanic. Rather, almost everything here received a wide release at some point.

That makes for an interesting horror library indeed, one that balances total schlock from Roger Corman with acclaimed works by the likes of Guillermo Del Toro and Stanley Kubrick. There are strange, foundational early horror films, such as Haxan or Vampyr, along with classics of world cinema like Japan’s Kwaidan, Onibaba and House. There are also indie gems like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, or The Witch.

Regardless, of all the major streamers, Max likely has the horror library most focused on what you’d call older “classics,” rather than newer releases—fine with us, considering that segment tends to be less well represented.

Here, then, are 40 best horror movies streaming on Max Now.

You may also want to consult the following horror-centric lists:

The 100 best horror films of all time.

The 100 best vampire movies of all time.

The 50 best zombie movies of all time.

The 50 best movies about serial killers.

The 50 best slasher movies of all time

The 50 best ghost movies of all time.

The best horror movies streaming on Netflix.

The best horror movies streaming on Amazon Prime.

The best horror movies streaming on Hulu.

The best horror movies streaming on Shudder.

1. The Witch

Year: 2016

Year: 2016

Director: Robert Eggers

Stars: Anya Taylor-Joy, Ralph Ineson, Kate Dickie

Rating: R

From its first moments, The Witch strands us in a hostile land. We watch (because that’s all we can do, helplessly) as puritan patriarch William (Ralph Ineson) argues stubbornly with a small council, thereby causing his family’s banishment from their “New England” community. We watch, and writer-director Robert Eggers holds our gaze while a score of strings and assorted prickly detritus—much like the dialogue-less beginning to There Will be Blood —rise to a climax that never comes. It’s a long shot, breathing dread: The wagon lurches ever-on into the wilderness, piling the frontier of this New World upon the literal frontier of an unexplored forest. It’s 1620, and William claims, “We will conquer this wilderness.” Eggers’ “New England Folk Tale” is a horror film swollen with the allure of the unknown. To say that it’s reminiscent of the Salem Witch Trials, which take place 70 years after the events in the film, would be an understatement—the inevitable consequences of such historic mania looms heavily over The Witch. All of this Eggers frames with a subconscious knack for creating tension within each shot, rarely relying on jump scares or gore, instead mounting suspense through one masterful edit after another. The effect, then, is that of a building fever dream in which primeval forces—lust, defiance, hunger, greed—simmer at the edges of experience, avoided but never quite conquered. But what’s most convincing is the burden of puritanical spirituality which blankets the film’s every single moment, a pall through which every character—especially teenage Thomasin (Anya Taylor Joy)—struggles to be, simply, a regular person. There is no joy in their worship, there is only gravitas: prayers, fasting, penitence and fear. And it’s that fear which drives the film’s horror, which eventually makes even us viewers believe that, at the fringes of civilization, at the border of the unknown, God has surely abandoned these people. —Dom Sinacola

2. Kwaidan

Year: 1964

Year: 1964

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Stars: Rentaro Mikuni, Tatsuya Nakadai, Katsua Nakamura, Osamu Takizawa, Noboru Nakaya

Rating: NR

Ghost stories don’t get much more gorgeous than the four in Masaki Kobayashi’s sprawling Kwaidan. Between two acerbically political and widely lauded samurai epics, Hara-kiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967), Kobayashi led what was then Japan’s most expensive cinematic production ever, an anthology film with its parts loosely connected by Lafcadio Hearn’s collection of Japanese folk tales and Kobayashi’s intuitive penchant for surreal, sweepingly lush sets. In “The Black Hair,” a selfish, impoverished ronin (Rentaro Mikuni) abandons his wife to marry into wealth, only to realize he made a dire mistake, plunging him into a gothic nightmare of decay and regret. “The Woman of the Snow” follows a craftsman (the always welcome Tatsuya Nakadai) doomed to have everything he loves stolen from him by a patient bureaucratic specter. The movie-unto-itself, “Hoichi the Earless,” pits the titular blind monk musician (Katsua Nakamura) against a family of ghosts, forcing the bard to recite—in hushed, heartbreaking passages on the biwa—the story of their wartime demise. Rapt with indelible images (most well known, perhaps, is Hoichi’s skin completely covered in the script of The Heart Sutra to ward off the ghosts’ influence), “Hoichi the Earless” is both deeply unnerving and quietly tragic, wrung with the sadness of Kobayashi’s admission that only forces beyond our control hold the keys to our fates. The fourth, and by far the weirdest, entry, “In a Cup of Tea,” is a tale within a tale, purposely unfinished because the writer (Osamu Takizawa) who’s writing about a samurai (Noboru Nakaya) who keeps seeing an unfamiliar man (Kei Sato) in his cup of tea is in turn attacked by the malicious spirits he’s conjuring. From these disparate fairy tales, plenty of fodder for campfires, Kobayashi creates a mythos for his country’s haunted past: We are nothing if not the pawns of all those to come before. —Dom Sinacola

3. Aliens

Year: 1986

Year: 1986

Director: James Cameron

Stars: Sigourney Weaver, Bill Paxton, Jenette Goldstein, Paul Reiser, Lance Henriksen, Michael Biehn

Rating: R

Runtime: 138 minutes

James Cameron colonizes ideas: Every beautiful, breathtaking spectacle he assembles works as a pointillist representation of the genres he inhabits–sci-fi, horror, adventure, thriller–its many wonderful pieces and details of worldbuilding swarming, combining to grow exponentially, to inevitably overshadow the lack at its heart, the doubt that maybe all of this great movie-making is hiding a dearth of substance at the core of the stories Cameron tells. An early example of this pilgrim’s privilege is Cameron’s sequel to Ridley Scott’s horror masterpiece, in which Cameron mostly jettisons Scott’s figurative (and uncomfortably intimate) interrogation of masculine violence to transmute that urge into the bureaucracy that only served as a shadow of authoritarianism in the first film. Cameron blows out Scott’s world, but also neuters it, never quite connecting the lines from the aggression of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation to the maleness of the military industrial complex, but never condoning that maleness, or that complex, either. Ripley’s (Sigourney Weaver) story about what happened on the Nostromo in the first film is doubted because she’s a woman, sure, but mostly because the story spells disaster for the corporation’s nefarious plans. Private Vasquez’s (Jennette Goldstein) place in the Colonial Marine unit sent to LV-426 to investigate the wiping out of a human colony is taunted, but never outright doubted, her strength compared to her peers pretty obvious from the start. Instead, in transforming Ripley into a full-on action hero/mother figure–whose final boss battle involves protecting her ersatz daughter from the horror of another mother figure–Cameron isn’t messing with themes of violation or the role of women in an economic hierarchy, he’s placing women by default at the forefront of mankind’s future war. It’s magnificent blockbuster filmmaking, and one of the first films to redefine what a franchise can be within the confines of a new director’s voice and vision.–Dom Sinacola

4. Godzilla

Year: 1954

Year: 1954

Director: Ishiro Honda

Stars: Sachio Sakai, Takashi Shimura, Momoko Kochi, Akira Takarada

Rating: NR

Early in Godzilla, before the monster is even glimpsed off the shore of the island of Odo, a local fisherman tells visiting reporter Hagiwara (Sachio Sakai) about the play they’re watching, describing it as the last remaining vestige of the ancient “exorcism” his people once practiced. Hagiwara watches the actors “sacrifice” a young girl to the calamitous sea creature to satiate its hunger and cajole it into leaving some fish for the people to enjoy—at least until the next sacrifice. Ishiro Hondo’s smash hit monster movie—the first of its kind in Japan, the most expensive movie ever made in the country at the time, not even a decade after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—is, after 20-something sequels over three times as many years, a surprisingly elegiac exorcism of its own, a reminder of one nation’s continuing trauma during a time when the rest of the world jonesed to forget.

As J Hoberman describes in his essay for the film’s Criterion release, much of Honda’s disaster imagery is “coded in naturalism,” a verite-like glimpse of the harrowing destruction wrought by the beast but indistinguishable from the aftermath of the Americans’ attacks in 1945, especially when the U.S. and Russia, among other powers, were testing H-bombs in the Pacific in the early 1950s, bathing the Japanese in even more radiation than that in which they’d already been saturated. And yet, Godzilla is a sci-fi flick, replete with a “mad” scientist in an eye patch and a human in a rubber dinosaur suit flipping over model bridges. That Honda handles such goofiness with an unrelentingly poetic hand, purging his nation’s psychological grief in broadly intimate volleys, is nothing short of astounding. Shots of Godzilla trudging through thick smoke, spotlights highlighting his gaping maw as the Japanese military’s weapons do nothing but shock the dark with beautiful chiaroscuro, have been rarely matched in films of its ilk (and in the director’s own legion of sequels); Honda saw gods and monsters and, with the world entering a new age of technological doom, found no difference between the two. —Dom Sinacola

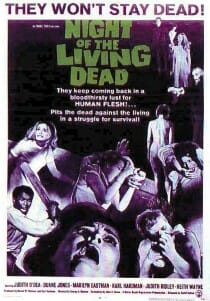

5. Night of the Living Dead

Year: 1968

Year: 1968

Director: George A. Romero

Stars: Judith O’Dea, Duane Jones, Marilyn Eastman, Karl Hardman, Judith Ridley, Keith Wayne

Rating: N/A

What more can be said of Night of the Living Dead? It’s pretty obviously the most important zombie film ever made, and hugely influential as an independent film as well. George Romero’s cheap but momentous movie was a quantum leap forward in what the word “zombie” meant in pop culture, despite the fact that the word “zombie” is never actually uttered in it. More importantly, it established all of the genre rules: Zombies are reanimated corpses. Zombies are compelled to eat the flesh of the living. Zombies are unthinking, tireless and impervious to injury. The only way to kill a zombie is to destroy the brain. Those rules essentially categorize every single zombie movie from here on out—either the film features “Romero-style zombies,” or it tweaks with the formula and is ultimately noted for how it differs from the Romero standard. It’s essentially the horror equivalent of what Tolkien did for the idea of high fantasy “races.” After The Lord of the Rings, it became nearly impossible to write contrarian concepts of what elves, dwarves or orcs might be like. Romero’s impact on zombies is of that exact same caliber. There hasn’t been a zombie movie made in the last 50-plus years that hasn’t been influenced by it in some way, and you can barely hold a conversation on anything zombie-related if you haven’t seen it—so go out and watch it, if you haven’t. The film still holds up well, especially in its moody cinematography and stark, black-and-white images of zombie arms reaching through the windows of a rural farmhouse. Oh, and by the way—NOTLD is public domain, so don’t get tricked into buying it on a shoddy DVD. —Jim Vorel

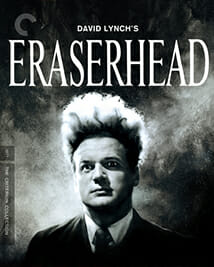

6. Eraserhead

Year: 1977

Year: 1977

Director: David Lynch

Stars: Jack Nance, Charlotte Stewart, Allan Joseph

Rating: R

It can be a painful experience to watch a film and have no idea what it’s about—to have the film’s meaning nagging at the core of you, always out of reach. Yet, that’s exactly the molten, subterranean fuel that pushes David Lynch’s visions forward, and with his debut, the perplexing and terrifying Eraserhead, the director offers no consolation for the encroaching feeling that with him we’ll never find any sort of logical mooring to keep our psyches safe. A simple tale about a funny-haired worker (Jack Nance) trundling nervously through a phantasmagoric industrial landscape, in the process fathering a mutant turtle-looking baby who he’s left to raise after his new wife abandons her “family,” Eraserhead is an astounding act of burying independently-minded cinematic experimentation in the popular consciousness. You may not know much about Eraserhead, but you probably know what it is. And whether or not it’s a meditation on the horrors of fatherhood, or a glimpse of the weird devolution of physical intimacy in a dying ecosystem, or a groundbreaking work of DIY sound design, or whatever—Eraserhead is a black hole of influence. It’s gross, it’s soul-stirring, it’s a visceral nightmare, and to this day, it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen before. Which may or may not be a compliment. I can’t be sure. —Dom Sinacola

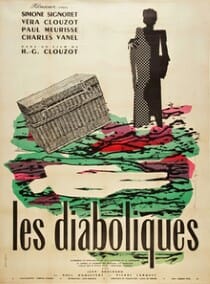

7. Les Diaboliques

Year: 1955

Year: 1955

Director: Henri-Georges Clouzot

Stars: Véra Clouzot, Paul Meurisse, Simone Signoret

Rating: NR

Watching Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques through the lens of the modern horror film, especially the slasher flick—replete with un-killable villain (check); ever-looming jump scares (check); and a “final girl” of sorts (check?)—one would not have to squint too hard to see a new genre coming into being. You could even make a case for Clouzot’s canonization in horror, but to take the film on only those terms would miss just how masterfully the iconic French director could wield tension. Nothing about Les Diaboliques dips into the scummy waters of cheap thrills: The tightly wound tale of two women, a fragile wife (Véra Clouzot) and severe mistress (Simone Signoret) to the same abusive man (Paul Meurisse), who conspire to kill him in order to both reel in the money rightfully owed the wife, and to rid the world of another asshole, Diaboliques may not end with a surprise outcome for those of us long inured to every modern thriller’s perfunctory twist, but it’s still a heart-squeezing two hours, a murder mystery executed flawlessly. That Clouzot preceded this film with The Wages of Fear and Le Corbeau seems as surprising as the film’s outcome: By the time he’d gotten to Les Diaboliques, the director’s grasp over pulpy crime stories and hard-nosed drama had become pretty much his brand. That the film ends with a warning to audiences to not give away the ending for others—perhaps Clouzot also helped invent the spoiler alert?—seems to make it clear that even the director knew he had something devilishly special on his hands. —Dom Sinacola

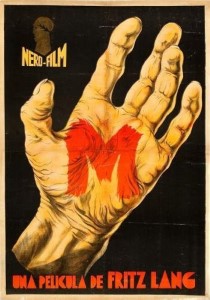

8. M

Year: 1931

Year: 1931

Director: Fritz Lang

Stars: Peter Lorre, Otto Wernicke, Gustaf Grundgens

Rating: PG-13

It’s rather amazing to consider that M was the first sound film from German director Fritz Lang, who had already brought audiences one of the seminal silent epics in the form of Metropolis. Lang, a quick learner, immediately took advantage of the new technology by making sound core to M, and to the character of child serial killer Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), whose distinctive whistling of “In the Hall of the Mountain King” is both an effectively ghoulish motif and a major plot point. It was the film that brought Peter Lorre to Hollywood’s attention, where he would eventually become a classic character actor: The big-eyed, soft-voiced heavy with an air of anxiety and menace. Lang cited M years later as his favorite film thanks to its open-minded social commentary, particularly in the classic scene in which Beckert is captured and brought before a kangaroo court of criminals. Rather than throwing in behind the accusers, Lang actually makes us feel for the child killer, who astutely reasons that his own inability to control his actions should garner more sympathy than those who have actively chosen a life of crime. “Who knows what it is like to be me?” he asks the viewer, and we are forced to concede our unfitness to truly judge.—Jim Vorel

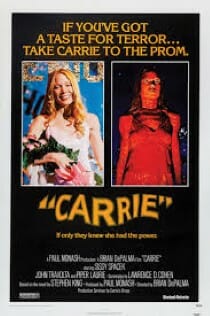

9. Carrie

Year: 1976

Year: 1976

Director: Brian de Palma

Stars: Sissy Spacek, Piper Laurie, John Travolta, P.J. Soles

Rating: R

The tropes and individually famous scenes of Carrie are so well known and ingrained into the pop cultural consciousness that you’d be forgiven for thinking you didn’t really need to see the original film to understand what makes it significant. But Carrie is much more than a precariously balanced bucket of pig’s blood: It’s a film that vacillates between darkly humorous and legitimately disturbing, mean-spirited and cruel, that terrifying mix of tones set immediately by what happens to poor Carrie White (Sissy Spacek) in the school’s locker room. Rarely has abject terror and helplessness been so perfectly captured as it is here, Carrie desperately, pathetically clinging to her classmates in terror of her first menstruation, only to be derided and pelted with tampons as she lays in a screaming heap. There’s simply no coming back from the kinds of humiliations she suffers, and none of her peers care to find out that Carrie’s home life is even more abusive. Spacek was rightly rewarded with an Oscar nomination for her performance in this, the first film adaptation of a Stephen King work, as was Piper Laurie as her mother–this is back in the ’70s when not one but two actresses from a horror film could actually receive Academy Award nominations (my how things have changed). Carrie is a brisk film which thrives on those two strong, central performances, building to the gloriously cathartic orgy of revenge we all know is coming. —Jim Vorel

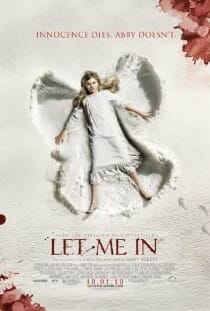

10. Let Me In

Year: 2010

Year: 2010

Director: Matt Reeves

Stars: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Chloe Grace Moretz, Elias Koteas, Richard Jenkins

Rating: R

Practically more supernatural a creature than its starring monster, Let Me In is not only an Americanized adaptation of a foreign film that isn’t a waste of everyone’s time, it’s arguably superior than the film it’s based upon. Like the original Swedish film, Let the Right One In, Matt Reeves’ update teases a remarkable amount of tension and intrigue through meticulous plotting and arresting imagery. Though set in Los Alamos, New Mexico, rather than Stockholm, the choice of place for relocation initially seems an odd one—but it turns out it’s not the icy Swedish darkness that harbors the sense of unease. It’s the isolation of a 12-year-old boy, neglected by parents and any real parental figure. Owen’s (Kodi Smit-McPhee) bond with the eternally youthful vampire Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz) is as effective and chilling here as it is in the original, thanks in no small part to its two phenomenal young leads. No question there’s a modern horror classic here, from the unlikeliest of origins. —Scott Wold

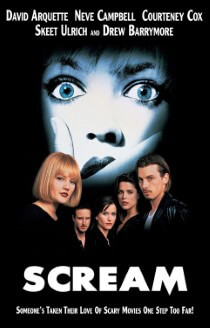

11. Scream

Year: 1996

Year: 1996

Director: Wes Craven

Stars: Neve Campbell, Skeet Ulrich, David Arquette, Courteney Cox, Matthew Lillard, Rose McGowan, Drew Barrymore

Rating: R

Before Scary Movie or A Haunted House were even ill-conceived ideas, Wes Craven was crafting some of the best horror satire out there. And although part of Scream’s charm was its sly, fair jabs at the genre, that didn’t keep the director from dreaming up some of the most brutal knife-on-human scenes in the ’90s. With the birth of the “Ghost Face” killer, Craven took audiences on a journey through horror-flick fandom, making all-too-common tricks of the trade a staple for survival: sex equals death, don’t drink or do drugs, never say “I’ll be right back.” With a crossover cast of Neve Campbell, Courteney Cox, David Arquette, Matthew Lillard, Rose McGowan and Drew Barrymore (OK, for like 10 minutes), Scream arrived with a smart, funny take on a tired genre. It wasn’t the first film of its kind, but it was the first one to be seen by a huge audience, which went a long way in raising the “genre IQ” of the average horror fan. —Tyler Kane

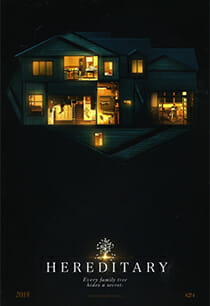

12. Hereditary

Year: 2018

Year: 2018

Director: Ari Aster

Stars: Toni Collette, Alex Wolff, Milly Shapiro, Ann Dowd, Gabriel Byrne

Rating: R

Ari Aster’s debut film begins in miniature. Later we learn of the trade Annie (Toni Collette), the film’s family’s matriarch, plies—meticulously designing doll-house-sized vignettes of the many domestic traumas she’s experienced, and still does, throughout her life, not for children but for art gallery spaces—though in the moment, in the beginning of Hereditary, the effect simply alludes to Aster’s ancestral preoccupations. From a tree house, pulling back through Annie’s workshop window, cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski’s camera pans to a tiny recreation of the house we’re currently within, then pushes into the simulacrum of high school student Peter Graham’s (Alex Wolff) bedroom, which transforms into the room itself, perspectives already ruined so early in the film. Father Steve (Gabriel Byrne) enters to give his late-snoozing son the black suit needed to attend his late grandmother’s memorial. Aster’s intent, as is the case throughout Hereditary, is both blunt and oblique: worlds exist within worlds, shadows within that which casts them, or vice versa, reality represented like the rings of a tree or the spirals of DNA holding untold secrets within the cores of whoever we are. Colin Stetson’s brain-churning score rattles the frame’s edges; menace looms—and menace soon unfolds, tragedies upon tragedies. The Graham family unravels over the course of Hereditary, which derives its power from testing the binds that force families together, teasing their strength as each family member must confront, kicking and screaming (or in Collette’s case: making the noise of one’s soul fleeing through every orifice), just how superficial those binds can be. In the absence of a reason for all of this happening, there is inevitability; in the absence of resolution there is only acceptance. —Dom Sinacola

13. Onibaba

Year: 1964

Year: 1964

Director: Kineto Shindo

Stars: Nobuko Otowa, Jitsuko Yoshimura, Kei Sat?, Taiji Tonoyama

Rating: NR

Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba will make you sweat and give you chills all at once, with its power found in Shindo’s blend of atmosphere and eroticism. It’s a sexy film, and a dangerous film, and in its very last moments a terrifying, unnerving film where morality comes full circle to punish its protagonists for their foibles and their sins. There’s a classicism to Onibaba’s drama, a sense of cosmic comeuppance: Characters do wrong and have their wrongs visited upon them by the powers that be. (In this case, Shindo.) But what makes the film so damn scary isn’t the fear of retribution passed down from on high, it’s the human element, the common thread sewn in a number of modern horror movies where the true monster is always us. Did demons, or demonic idols, foment the civil war that serves as Onibaba’s backdrop? Are spirits culpable for the ruthless survivalism of the film’s two main characters? Nope and nope. Put a checkmark next to “mankind” in reply to both questions, and then wish that demons and spirits were real, because that’d be preferable to acknowledging reality. Back a human into a corner, and they’ll throw you into a ditch, leave you for dead and steal your shit, and what’s more unsettling than “better you than me” as a guiding principle for living? —Andy Crump

14. Midsommar

Year: 2019

Year: 2019

Director: Ari Aster

Stars: Florence Pugh, Jack Reynor, William Jackson Harper, Vilhelm Blomgren, Ellora Torchia, Archie Madekwe, Will Poulter

Rating: R

Christian (Jack Reynor) cannot give Dani (Florence Pugh) the emotional ballast she needs to survive. This was probably the case even before the family tragedy that occurs in Midsommar’s literal cold open, in which flurries of snow limn the dissolution of Dani’s family. We’re dropped into her trauma, introduced to her only through her trauma and her need for support she can’t get. This is all we know about her: She is traumatized, and her boyfriend is barely decent enough to hold her, to stay with her because of a begrudging obligation to her fragile psyche. His long, deep sighs when they talk on the phone mirror the moaning, retching gasps Pugh so often returns to in panic and pain. Her performance is visceral. Midsommar is visceral. There is viscera, just, everywhere. As in his debut, Hereditary, writer-director Ari Aster casts Midsommar as a conflagration of grief—as in Hereditary, people burst into flames in Midsommar’s climactic moments—and no ounce of nuance will keep his characters from gasping, choking and hollering all the way to their bleakly inevitable ends. Moreso than in Hereditary, what one assumes will happen to our American 20-somethings does happen, prescribed both by decades of horror movie precedent and by the exigencies of Aster’s ideas about how human beings process tragedy. Aster births his worlds in pain and loss; chances are it’ll only get worse. —Dom Sinacola

15. The Conjuring

Year: 2013

Year: 2013

Director: James Wan

Stars: Vera Farmiga, Patrick Wilson, Ron Livingston, Lili Taylor

Rating: R

Let it be known: James Wan is, in any fair estimation, an above average director of horror films at the very least. The progenitor of big money series such as Saw and Insidious has a knack for crafting populist horror that still carries a streak of his own artistic identity, a Spielbergian gift for what speaks to the multiplex audience without entirely sacrificing characterization. Several of his films sit just outside the top 100, if this list were ever to be expanded, but The Conjuring can’t be denied as the Wan representative because it is far and away the scariest of all his feature films. Reminding me of the experience of first seeing Paranormal Activity in a crowded multiplex, The Conjuring has a way of subverting when and where you expect the scares to arrive. Its haunted house/possession story is nothing you haven’t seen before, but few films in this oeuvre in recent years have had half the stylishness that Wan imparts on an old, creaking farmstead in Rhode Island. The film toys with audience’s expectations by throwing big scares at you without standard Hollywood Jump Scare build-ups, simultaneously evoking classic golden age ghost stories such as Robert Wise’s The Haunting. Its intensity, effects work and unrelenting nature set it several tiers above the PG-13 horror against which it was primarily competing. It’s interesting to note that The Conjuring actually did receive an “R” rating despite a lack of overt “violence,” gore or sexuality. It was simply too frightening to deny, and that is worthy of respect. —Jim Vorel

16. Eyes Without a Face

Year: 1959

Year: 1959

Director: Georges Franju

Stars: Édith Scob, Pierre Brasseur, Francois Guerin

Rating: NR

I remember seeing my first Édith Scob performance back in 2012, when Leos Carax’s Holy Motors made its way to U.S. shores, in which she donned a seafoam mask, every bit as blank and lacking in expression as Michael Myers’, in the film’s ending. I thought to myself, “Gee, that’d play like gangbusters in a horror movie.” What an idiot I was: Scob had already appeared in that movie, Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, an icy, poetic and yet lovingly made film about a woman and her mad scientist dad, who just wants to kidnap young ladies that share her facial features in hopes of grafting their skin onto her own disfigured mug. (That’s father of the year material right there.) Of course, nothing goes smoothly in the film’s narrative, and the whole thing ends in tears—plus a frenzy of canine bloodlust. Director Franju plays Eyes Without a Face in just the right register, balancing the unnerving, the perverse and the intimate, as the most enduring pulpy horror tales tend to do. If Franju gets to claim most of the credit for that, at least save a portion for Scob, whose eyes are the single best special effect in the film’s repertoire. Hers is a performance that stems right from the soul. —Andy Crump

17. Ugetsu

Year: 1953

Year: 1953

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Stars: Mitsuko Mito, Masayuki Mori, Eitaro Ozawa, Kinuyo Tanaka

Rating: NR

During an incredibly prolific point at the end of his career, Kenji Mizoguchi released Ugetsu between The Life of Oharu (1952) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954), only three years before his death. Like in those two films, Mizoguchi set Ugetsu in feudal Japan, using the country’s civil war as a milieu through which he could explore the ways in which ordinary people are kept from seeing to their basest needs, ground instead to dirt by forces far beyond their control. So it goes with two couples: Genjuro (Masayuki Mori), a potter hoping to profit from wartime, and his wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka); Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa) and Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), who rightly indicts her husband’s dreams of being a well-decorated samurai as foolish, especially considering that Tobei shows no signs of physical mettle, let alone a brain with any sense of militaristic prowess. Ignoring both their wives’ grave concerns and the ecliptic tide of war, the two men set out to make one last big bid for fame and fortune, setting out only to find a country haunted, literally sometimes, by casualties. Ugetsu is a lushly elemental film, epitomized by Mizoguchi’s long takes and aloof mise-en-scene, highlighted the callousness of what he was trying to capture. Seamlessly shifting between ethereal setpieces—the iconic rendezvous between boats, set amidst a hellish waterscape of mist and portent is perhaps the crux around which the film unwinds—and grittier clusterfucks of mass pain in progress, Mizoguchi conjures up a sense of inevitability: No matter how much these characters learn about love or family or themselves, they are doomed. Misery unfolds supernaturally and pointlessly in Ugetsu—so much so that by the time anyone’s noticed that tragedy’s struck, it’s already well-burrowed into the bones of those at its mercy. —Dom Sinacola

18. It Comes at Night Year: 2017

Year: 2017

Director: Trey Edward Shults

Stars: Joel Edgerton, Christopher Abbott, Carmen Ejogo, Riley Keough, Kelvin Harrison Jr.

Rating: R

It Comes at Night is ostensibly a horror movie, moreso than Shults’s debut, “Krisha“:https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2016/03/krisha.html, but even Krisha was more of a horror movie than most measured family dramas typically are. Perhaps knowing this, Shults calls It Comes at Night an atypical horror movie, but—it’s already obvious after only two of these—Shults makes horror movies to the extent that everything in them is laced with dread, and every situation suffocated with inevitability. For his sophomore film, adorned with a much larger budget than Krisha and cast with some real indie star power compared to his previous cast (of family members doing him a solid), Shults imagines a near future as could be expected from a somber flick like this. A “sickness” has ravaged the world and survival is all that matters for those still left. In order to keep their shit together enough to keep living, the small group of people in Shults’s film have to accept the same things the audience does: That important characters will die, tragedy will happen and the horror of life is about the pointlessness of resisting the tide of either. So it makes sense that It Comes at Night is such an open wound of a watch, pained with regret and loss and the mundane ache of simply existing: It’s trauma as tone poem, bittersweet down to its bones, a triumph of empathetic, soul-shaking movie-making. —Dom Sinacola

19. Evil Dead Rise

Year: 2023

Year: 2023

Director: Lee Cronin

Stars: Alyssa Sutherland, Lily Sullivan, Morgan Davies, Gabrielle Echols, Nell Fisher

Rating: R

If there’s anything that could have an entire audience cheering when a possessed pre-teen drags a cheese grater across her aunt’s calf like it’s a fresh block of cheddar, it’s an Evil Dead movie. The first film to grace the beloved franchise in a decade, Evil Dead Rise is everything you could ask for from an Evil Dead flick: It’s disgusting enough to make you physically recoil, it’s funny as hell and, perhaps most importantly, it might just wield more blood than I’ve ever seen in a movie. If the film has one downfall, it’s that director Cronin sometimes sacrifices too much to get his shocking, gore-filled images on the screen. The film only works if the five main characters aren’t able to leave their apartment. As a result, no one tries particularly hard to. And while I am endlessly thankful for all of the horrible, depraved things that I witnessed in that theater, at times I could imagine Cronin asking “What is the grossest thing I could put in a movie?” and working backwards from there, without paying too much mind to the plot. Still, you have to hand it to him: Cronin gave Evil Dead fans (myself included) precisely what they wanted with Rise. All of the gore, humor and callbacks you could possibly ask for, packaged into 90 minutes. You can’t ask for much more than that—though it’ll be a while before I eat grated cheese again. —Aurora Amidon

20. The Lure

Year: 2015

Year: 2015

Director: Agnieszka Smoczynska

Stars: Marta Mazurek, Michalina Olszanska

Rating: NR

In Filmmaker Magazine, director Agnieszka Smoczynska called The Lure a “coming-of-age story” born of her past as the child of a nightclub owner: “I grew up breathing this atmosphere.” What she means to say, I’m guessing, is that The Lure is an even more restlessly plotted Boyhood if the Texan movie rebooted The Little Mermaid as a murderous synth-rock opera. (OK, maybe it’s nothing like Boyhood.)

Smoczynska’s film resurrects prototypical fairy tale romance and fantasy without any of the false notes associated with Hollywood’s “gritty” reboot culture. Poland, the 1980s and the development of its leading young women provide a multi-genre milieu in which the film’s cannibalistic mermaids can sing their sultry, often violently funny siren songs to their dark hearts’re content. While Ariel the mermaid Disney princess finds empathy with young girls who watch her struggle with feelings of longing and entrapment, The Lure’s flesh-hungry, viscous, scaly fish-people are a gross, haptic and ultimately effective metaphor for the maturation of this same audience. In the water, the pair are innocent to the ways of humans (adults), but on land develop slimes and odors unfamiliar to themselves and odd (yet strangely attractive) to their new companions. Reckoning with bodily change, especially when shoved into the sex industry like many immigrants to Poland during the collapse of that country’s communist regime in the late ’80s, the film combines the politics of the music of the time with the sexual politics of a girl becoming a woman (and the musicals that exploit the same). And though The Lure may bite off more human neck than it can chew, especially during its music-less plot wanderings, it’s just so wonderfully consistent in its oddball vision you won’t be able to help but be drawn in by its mesmerizing thrall. —Jacob Oller

21. Häxan

Year: 1922

Year: 1922

Director: Benjamin Christensen

Stars: Clara Pontoppidan, Maren Pedersen, Oscar Stribolt

Rating: NR

A truly unique silent film, Häxan is presented as both a historical documentary and a warning against hysteria, but to a modern audience it plays with a confounding blend of genuine horror and humor, both intentional and not. Director Christensen based his depictions of witch trials on the real-life horrors codified in the Malleus Maleficarum, the 15th century “hammer of witches” used by clergy and inquisitors to persecute women and people with mental illness. The dreamlike—make that nightmarish—dramatization of these torture sequences were almost unthinkably extreme for the time, leading to the film’s banning in the U.S. But put simply: There’s iconography in Häxan that grabs hold of you. Puffy-cheeked devils with long tongues lolling lazily out of their mouths. Naked men and women crawling and cavorting in circles of demons, lining up to literally kiss demonic asses. Scenes of torture straight out of Albrecht Dürer woodcuts or Divine Comedy illustrations. The grainy silence of black and white only makes Häxan more otherworldly to watch today—it feels like some kind of bleak Satanic relic that humankind was never supposed to witness. This is one silent film you won’t want on with children in the room.

Häxan is also an oddball testament to one of the enduring qualities of human nature, which is our tendency to be snarky assholes in our appraisal of previous generations. Christensen’s film often points a finger at the “superstitious” and “religious fanatic” persons of 1922 with a modern sense of cynicism and superiority in its implication that society had long since grown past such things. Obviously, almost 100 years later, we know this is not the case: We’re still deeply informed by the dusty trappings of religion and supernatural superstition, just as Christensen’s contemporaries were. Watching Häxan, then, becomes a different kind of warning: to not think too highly of our own sophistication, or make the assumption that we have in some way evolved from what we once were. People, as it turns out, have always been this way, and may always be. —Jim Vorel

22. The Blackcoat’s Daughter

Year: 2016

Year: 2016

Director: Osgood Perkins

Stars: Emma Roberts, Kiernan Shipka, Lucy Boynton, Lauren Holly, James Remar

Rating: R

Looking at his first two horror features, it becomes clear that director Osgood Perkins seems to have a distinct distaste for both plot and film convention. His films defy easy description, as anyone who watched I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House could attest. The Blackcoat’s Daughter, meanwhile, was completed and exhibited as early as 2015 under the title February, but then floated around for years until A24 gave it a release. Compared with Pretty Thing, Blackcoat’s Daughter is at least easier to grasp and marginally brisker, which makes it more effective overall. Perkins’ style is languid, atmospheric and deliberate, favoring repetition and a slowly multiplying sense of unease and impending doom. The story follows two high school-aged students who are both left relatively alone at their uptight Catholic boarding school over break when their parents fail to pick them up. As one descends into what is implied to be either madness or demonic possession, the events are interwoven with another story about a young woman journeying on the road in the direction of the boarding school. The two stories inevitably intertwine. The film’s pace sometimes leaves something to be desired, but patience is largely repaid by its final third, which contains several moments genuinely disturbing in their violence and transgressive imagery. In the end, The Blackcoat’s Daughter comes together significantly more neatly and logically than one might consider while watching its first hour, rewarding careful attention to detail throughout. —Jim Vorel

23. Vampyr

Year: 1932

Year: 1932

Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer

Stars: Julian West, Maurice Schultz, Rena Mandel, Jan Hieronimko, Sybille Schmitz, Henriette Gerard

Rating: NR

While wandering the countryside, a naïve young man with a propensity for the occult stumbles upon a castle where he learns that the owner’s teenage daughter is slowly descending into vampirism. Upon seeing the village doctor trying to poison the girl, the boy intervenes and complications, naturally, ensue. Notable as being one of the few early vampire movies not even passingly based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Vampyr nonetheless brought very little joy to its creator, legendary Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer (he of The Passion of Joan of Arc). Forced to shoot the production in three different languages (French, German and English), Dreyer’s first sound film experience was a proverbial trial by fire. To add salt to the infuriating production, the film was released only after some fairly heavy censoring. The reception was no less brutal, with critics delivering scathing reviews. As the years have passed by and an appreciation for Dreyer has grown, however, so has an appreciation for the film, with many modern critics citing its subversive take on sexuality to be years ahead of its time. Shot with the delicacy and elegance of a dream, Dreyer quickly plunges the viewer into an expressionistic hellscape of shadows and dread. Though it may be a bit slow for some audiences, even with a sparse 73-minute runtime, Vampyr is a intense mood piece that picked up where Nosferatu left off. —Mark Rozeman

24. Paranormal Activity

Year: 2007

Year: 2007

Director: Oren Peli

Stars: Katie Featherston, Micah Sloat

Rating: R

Here’s a statement: Paranormal Activity is the most wrongly derided horror film of the last decade, especially by horror buffs. That’s what happens in the wake of massive overnight success, and immediately derivative, inferior sequels: The original gets dragged down by its progeny. The original Paranormal Activity is a masterful piece of budget filmmaking. For $15,000, Oren Peli made what is probably the most effective “for the price” horror movie ever released, surpassing The Blair Witch in terms of both tension and narrative while pulling off incredibly unnerving minimalist effects. Yes, there are some stupid, “I’m in a horror movie” choices by the characters, and yes, Micah Sloat’s “get out here so I can punch you, demon!” attitude is irritating, but it’s calculated to be that way. Sloat is a reflection of the toxic “man of the house” attitude, a guy who would rather be terrorized than accept outside help. Meanwhile, Katie Featherston’s realistic performance as a young woman slowly unraveling is a thing of beauty. But beyond performances, or effects, Paranormal Activity is a brilliant case study in slowly building tension, and in raising an audience’s blood pressure. I know: I saw this film in theaters when it was still in limited release, and I can honestly say I’ve never been in a movie theater audience that was more terrified. How could I tell? Because they were so loud in the moments of calm before each scare (the most dead giveaway of all: when a young man turns to his friends to assure them how not-nervous he is). This was just such an event—there were actually ushers standing at the entrance ramps throughout the entire film, just watching the audience watch the movie. I’ve yet to ever see that happen again. Deride all you want, but the arrival of Paranormal Activity scared the hell out of us. —Jim Vorel

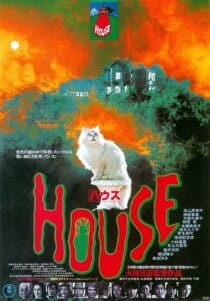

25. Hausu

Year: 1977

Year: 1977

Director: Nobuhiko Obayashi

Stars: Kimiko Ikegami, Miki Jinbo, Ai Matubara, Kumiko Oba, Mieko Sato, Eriko Tanaka

Rating: NR

Oh, how to describe Hausu? Anyone who has seen this crazed Japanese mishmash of horror, comedy and fantasy knows this is no easy task—it’s simultaneously as simple as saying “It’s about some girls who go to a haunted house,” and much more complicated. Hausu has often been described as being “like Jaws, but with a house,” but the comparison isn’t exactly accurate—where Spielberg’s film is classic adventure, Obayashi’s is like a bad acid trip, sporting trippy, day-glo color schemes and mind-bending visuals. Animated cats, disembodied flying heads and stop-motion monsters are all par for the course as Hausu goes for the jugular, seemingly trying to overwhelm the viewer with an all-out assault on the senses. As a piece of modern camp spectacle it’s top tier, but it would be a shame to overlook the genuinely imaginative visual effects and how they would seem to presage the likes of Evil Dead 2 in the years to come. If there’s another film where a woman is eaten by a living, evil piano, I haven’t yet seen it. —Jim Vorel

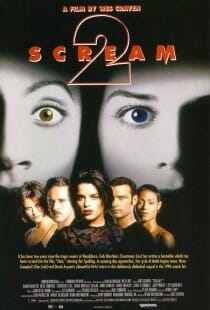

26. Scream 2

Year: 1997

Year: 1997

Director: Wes Craven

Stars: Neve Campbell, Courteney Cox, David Arquette, Liev Schreiber, Jamie Kennedy, Laurie Metcalf, Jerry O’Connell, Timothy Olyphant

Rating: R

It was going to be hard to follow up the original Scream for plenty of reasons: Aside from it being one of the more innovative, self-aware horror films in years, Wes Craven killed off all of its bad guys in the final scenes of the movie. Here’s where Scream 2—a respectable follow-up and one that sets the stage for all of the film’s lesser sequels—comes into play. It follows a new string of “ghost face” murders, this time centering around the creation of Stab, a film based upon the Woodsboro murders. As always, the film is painfully critical of the horror movie genre while still scaring the pants off audiences in voice-morphed, quizzical phone calls and Ghost Face pop-ups. It remains the only Scream sequel to approach the original in terms of overall quality, thanks to its ability to turn over new leaves in examining the conventions of film sequels. —Tyler Kane

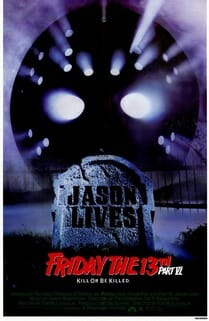

27. Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives

Year: 1986

Year: 1986

Director: Tom McLoughlin

Stars: Thom Matthews, Jennifer Cooke, David Kagen, C.J. Graham, Dan Bradley

Rating: R

It’s a bit of a sleeper pick, but one that has become more defensible over time as its stock grows–of all the Friday the 13th movies, the most purely entertaining entry falls right in the middle of the series: Part VI, Jason Lives. A near perfect amalgam of everything we love about mid ’80s era slasher movies, it’s an expertly balanced melange of jump scares, goofy characters, comic ultraviolence, spooky settings and gratuitous titillation. Tommy Jarvis from The Final Chapter returns as a grown man after the disappointing and confusing fifth installment of the series, unable to accept the fact that Jason is actually dead. Naturally, his attempts to make sure end up resulting in Voorhees actually reanimating as a truly undead killing machine for the first time, and we’re off to the races. Jason stacks up a truly absurd body count in this entry, dispatching minor characters and cannon fodder with the greatest of ease and stylish panache. The film winks at the audience quite a bit, critiquing their taste in tawdry slashers even while it delivers one of the most fun, vibrant examples of the genre from the mid-’80s. It’s self-aware in all the best ways, because its awareness never stops it from giving the paying audience exactly what they came to see. —Jim Vorel

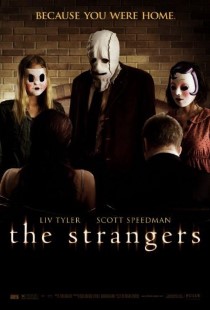

28. The Strangers

Year: 2008

Year: 2008

Director: Bryan Bertino

Stars: Liv Tyler, Scott Speedman

Rating: R

When it arrived in 2008, some horror fans were perhaps a bit too eager to anoint The Strangers as an instant classic of the genre. A decade and one belated, uninspired sequel later, it’s easier to see the film for what it is: A well-crafted home invasion thriller that stands out for its less-is-more approach to building tension. Our characters, such as they are, are stand-ins for anyone in polite society–a man and a woman, in a failing relationship. They’re hardly unique, and that’s the point. Likewise, as opposed to the likes of Funny Games–to which The Strangers is often compared–we really don’t get a sense of the psyche of our antagonists. This is ultimately the scariest thing about them; their faceless blankness and simple, “because you were home” motivation. These people don’t proselytize to their victims; they just kill them because it’s fun. The film ultimately can’t quite sustain genuine fear into the third act, but its midpoint is pretty masterfully calculated–especially the scene in which Liv Tyler nervously paces the kitchen while an intruder lurks unseen in the background, completely silent. There’s a reason this is the enduring image that most fans remember from The Strangers today. —Jim Vorel

29. Scanners

Year: 1981

Year: 1981

Director: David Cronenberg

Stars: Michael Ironside, Jennifer O’Neill, Stephen Lack, Patrick McGoohan, Lawrence Dane

Rating: R

Everything to love about David Cronenberg rests squishy and bulging in Scanners—but this is before The Fly, before VIdeodrome, before Dead Ringers, and long before Naked Lunch—and so everything we love about Cronenberg is in Scanners, squishy and bulging and also with the slight gleam of nascent dew. To be sure, the body horror is egregious, and its tension visceral, but the bonus of Scanners is that, still so early in his career, Cronenberg had an obviously dubious time trying to figure out what kind of films he wanted to make. Sci-fi thriller, old-timey cyberpunk, grody procedural—Cronenberg litters his typical themes of transformation and transmutation throughout a story that, at practically any moment, feels like it could turn completely on its head. A head which would then, in a firework of brains and bone, explode—nothing if a gratuitous sign of genius things to come.—Dom Sinacola

30. Carnival of Souls

Year: 1962

Year: 1962

Director: Herk Harvey

Stars: Candace Hilligoss, Herk Harvey

Rating: PG

Carnival of Souls is a film in the vein of Night of the Hunter: artistically ambitious, from a first-time director, but largely overlooked in its initial release until its rediscovery years later. Granted, it’s not the masterpiece of Night of the Hunter, but it’s a chilling, effective, impressive tale of ghouls, guilt and restless spirits. The story follows a woman (Candace Hilligoss) on the run from her past who is haunted by visions of a pale-faced man, beautifully shot (and played) by director Herk Harvey. As she seemingly begins to fade in and out of existence, the nature of her reality itself is questioned. Carnival of Souls is vintage psychological horror on a miniscule budget, and has since been cited as an influence in the fever dream visions of directors such as David Lynch. To me, it’s always felt something like a movie-length episode of The Twilight Zone, and I mean that in the most complimentary way I can. Rod Serling would no doubt have been a fan. —Jim Vorel

31. Pet Sematary Year: 1989

Year: 1989

Director: Mary Lambert

Stars: Dale Midkiff, Fred Gwynne, Denise Crosby, Brad Greenquist, Michael Lombard

Rating: R

The book might be one of King’s biggest-selling works and the movie adaptation might have been a success at the box-office, but let’s face it: Pet Sematary has a really stupid premise. It’s essentially a pre-Romero, old-fashioned zombie tale with flesh-eating undead kitty cats and little boys. Don’t get me wrong, director Mary Lambert’s take on King’s novel probably represents the best possible cinematic outcome for this silly tale, with an overbearing gothic mood that unsettles the audience at every turn, and an admirably straight-faced execution that manages to give the project some gravitas. But at the end of the day, this is a movie that takes the idea of a zombie cat seriously, while also climaxing with an annoyingly clichéd genre twist. —Oktay Ege Kozak

32. From Dusk Till Dawn

Year: 1996

Year: 1996

Director: Robert Rodriguez

Stars: George Clooney, Quentin Tarantino, Harvey Keitel, Juliette Lewis, Ernest Liu, Salma Hayek

Rating: R

I can’t help but wonder, watching From Dusk Till Dawn, what the film might have looked like if Robert Rodriguez wrote it as well, rather than Quentin Tarantino. Would the Mexican vampire element have been introduced before the halfway mark? Probably. But there’s Tarantino for you, not content to tell one story—instead, he delivers what almost becomes two entirely separate movies starring the same characters. In the first half we get a crime dramedy about a pair of sociopathic brothers on the lam, taking hostages down the Mexico. When they finally get there, the switch flips and it turns into a gory vampire western. Both halves are entertaining in their own way, although genre purists who went in expecting a vampire film were probably perplexed by the lead-in to the payoff. That payoff is satisfyingly pulpy, though, and there’s a certain pleasure in going back to see the earlier era of George Clooney, when he thought the idea of fighting Mexican vampires seemed like a good career move. —Jim Vorel

33. Malignant

Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: James Wan

Stars: Annabelle Wallis, Maddie Hasson, George Young, Michole Briana White

Rating: R

Before anything else, horror director James Wan is a master of depicting possession. Of course, we see this in the prolific Conjuring series, where countless bodies are puppeteered by evil spirits. We also bear witness to it in the Saw franchise, where the sadistic influence of Jigsaw possesses his victims to mutilate themselves or others. The entirety of Wan’s career has pondered what it is exactly about the idea of possession that shakes us to our very cores. Decades after his cinematic debut, Malignant, or, more specifically, the film’s final moments, finally answers that question. Malignant follows Madison Lake (Annabelle Wallis), a young woman who, after being attacked by her abusive husband, becomes regularly consumed by visions of a hooded figure committing grisly murders. It isn’t long before Madison discovers that these aren’t just visions—they’re happening in real life. For much of Malignant, Wan relies on campy acting and jump scares to keep the solid, if not edging on unimaginative, story happily trodding along, and its viewers with it. He confidently holds back on revealing the film’s true genius until the final act, at which point it unexpectedly mutates into a masterclass of mind-bending, absurdist psychological horror. —Aurora Amidon

34. Friday the 13th Part IV: The Final Chapter

Year: 1984

Year: 1984

Director: Joseph Zito

Stars: Kimberly Beck, Peter Barton, Crispin Glover

Rating: R

Had the producers of the Friday the 13th series never decided to officially return Jason from the dead as a superpowered zombie in series highlight Jason Lives, then The Final Chapter would actually stand out all the more as the most perfect synthesis of the Friday the 13th formula, complete with a fittingly grisly end to the series antagonist. As is, it’s still one of the very best entries, consistently ranked near the top by fans for its characters, kills and an outstanding Jason performance by uncredited stuntman Ted White. It’s the film that gives us a young Corey Feldman as Tommy Jarvis, the inventive little boy who becomes the closest thing that Jason ever attains to a human arch-nemesis, and the source of his eventual undoing. Jason himself is near his best in The Final Chapter, having become gradually more and more powerful as the series continued–here, he has no trouble at all bursting through bolted doors in a single motion. And of course, no mention of The Final Chapter is complete without acknowledging the presence of Crispin Glover as the neurotic “Jimmy,” whose “spastic dance sequence”:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ocgj9tewHso has passed into slasher film legend as one of the genre’s most awkwardly hilarious moments. —Jim Vorel

35. John Dies at the End

Year: 2012

Year: 2012

Director: Don Coscarelli

Stars: Chase Williamson, Rob Mayes, Paul Giamatti, Clancy Brown, Glynn Turman, Doug Jones, Daniel Roebuck

Rating: R

Your ability to withstand the absurdity of John Dies at the End will depend almost entirely on if you’re able to tolerate nonlinear storylines and characters who, woven together, tax the lengths of the imagination. An oftimes crude and farcical combination of horror, drug culture, and philosophical sci-fi, it’s a film you won’t entirely grasp until you’ve seen it for yourself. Central is a drug known as “soy sauce,” which causes the user to see outside the concept of linear time, existing at all times at once, similar to the alien beings from Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. Also appearing: phantom limbs, an alien consciousness known as “Shitload,” a heroic dog, Paul Giamatti and an evil, interdimensional supercomputer. No drugs necessary—John Dies at the End will make you feel like you’ve already ransacked your medicine cabinet. —Jim Vorel

36. Cujo

Year: 1983

Year: 1983

Director: Lewis Teague

Stars: Dee Wallace, Daniel Hugh-Kelly, Danny Pintauro, Ed Lauter, Christopher Stone

Rating: R

Cujo is a very modest, intimate horror film, as sad as it is potentially frightening. There’s something really tragic in the degradation of Cujo the St. Bernard after he contracts rabies, the way his eyes and mental state begin to crumble in the face of the disease. He’s made into a monster, but it’s an unwilling transformation from his normally friendly state, a stripping away of non-sentient good-naturedness–one might call it a metaphor for the corrupting power of evil in society. It’s well-structured to lead itself to a long, tense stand-off between a mother, her young son and the dog, as they sit trapped in their car in the broiling heat, trying to make a decision between heatstroke or the vicious dog waiting for them outside. As if it needs to be said, you shouldn’t watch this if you’ve ever had any doubts about the loyalties of the family pooch, as it will only exacerbate them. —Jim Vorel

37. Cronos

Year: 1993

Year: 1993

Director: Guillermo del Toro

Stars: Federico Luppi, Ron Perlman, Claudio Brook, Margarita Isabel, Tamara Shanath

Rating: R

Even working with a small budget in his first feature film, the vitality of Guillermo Del Toro’s imagination was immediately on full display in Cronos, his Mexican vampire horror drama. Reflecting themes and visual elements that the director has continued to refine in The Devil’s Backbone, Pan’s Labyrinth and Crimson Peak, Cronos is a simply told but visually striking story about an antique shop owner who is slowly and unwittingly transformed into a vampire-like creature after a 450-year-old mechanical device clamps onto his arm and refuses to let go. At first he enjoys the new vitality of the transformation, before other parties come hunting for the device, turning the movie into almost a vampire crime story, as it were. Regardless, Cronos features a very sympathetic vampire at its core, an old man who is simply thrilled by what at first appears to be a new lease on life but eventually requires deadly sacrifices. It’s certainly not Del Toro’s most spellbinding feature, but it was an excellent debut. —Jim Vorel

38. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: Jane Schoenbrun

Stars: Anna Cobb, Michael J. Rogers

Rating: NR

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair isn’t straightforwardly a “horror” movie—even if the title reads like an invocation chanted by hypnotized cultists doomed to whatever fate awaits them at the fairgrounds. That, of course, is more or less exactly what it is, as evinced in the opening sequence, where young Casey (Anna Cobb) recites the phrase three times while staring wide-eyed at her computer monitor. Innocent enough, if firmly eerie. Then she pricks her finger with a button’s pin about two dozen times in rapid succession and streaks her blood on the screen (though just out of the audience’s line of sight) to conclude the ritual. All that’s left is to wait and see how joining in this online “game” changes her, as if undergoing a Cronenbergian rite of passage. What writer/director Jane Schoenbrun wants viewers to wonder is whether those changes are in earnest, and whether changes documented by other participants in the “World’s Fair challenge” are legit or staged. They’re unreliable narrators. To an extent, so is Casey—insomuch as teens stepping into the world solo for the first time can be relied on for anything resembling objectivity. There’s also the question of exactly where Casey draws the line between truth and macabre make-believe, and of course whether that belief is made up. Maybe there really is a ghost in the machine. Or maybe a life predominantly lived in a virtual space—because physical space is dominated by isolation and bad paternal relationships—naturally inclines people toward delusion at worst and an unerring sensation of disembodiment at best. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair concludes with ambiguity and atmospheric loss, as if we’re meant to consider leaving childhood behind as a form of tragedy. Spoken in Schoenbrun’s language, that process is painful, transformative and—first and foremost—an internal experience regardless of the movie’s stripped-down visual pleasures. Outside forces influence Casey, but Casey ultimately controls the direction those forces take her. In a way, that’s empowering. But Schoenbrun belies the collective dynamic implied in We’re All Going to the World’s Fair’s title with Casey’s lonesome reality.—Andy Crump

39. The Brood

Year: 1979

Year: 1979

Director: David Cronenberg

Stars: Oliver Reed, Samantha Eggar, Art Hindle

Rating: R

Even by the standards of David Cronenberg, The Brood is a particularly nasty piece of work. This is a meanspirited and misanthropic yarn that blends body horror and science fiction into a new-aged parable of revenge and repressed rage, erupting forth whether we want it to or not. The titular “brood” are a deformed band of what look like dwarf-like children, created not by mad science but new-age psychobabble—a woman turns her latent anger, fear and mental illness into a physical product, which becomes a series of small, psychically linked killer dwarves who are sent out to destroy those who caused her grief. Totally absurd? Oh, 100% accurate, but also just as deeply off putting as you’d expect the work of Cronenberg to be in so many cases. It’s a messed-up metaphor on the destructive power of pent-up bitterness, inspired by Cronenberg’s own rancorous divorce. —Jim Vorel

40. Friday the 13th Part VII: The New Blood

Year: 1988

Year: 1988

Director: John Carl Buechler

Stars: Lar Park Lincoln, Kevin Blair, Susan Blu, Terry Kiser

Rating: R

You can almost imagine the pitch meeting for Friday the 13th: The New Blood. A bunch of studio execs are sitting around a table. “But we’ve DONE these Jason movies,” says one. “What can we possibly do that we haven’t already done?” The room falls silent. A nebbish guy stands up and tentatively says the following: “What about psychic powers?” And the room bursts into applause. Because that’s what this fun, exuberant entry in the series gives us–an otherwise archetypal female protagonist who is set apart by her Carrie-esque telekinetic abilities. Just that one change allows for the application of a fresh coat of supernatural paint to the Jason Voorhees slasher primer. Jason is at his indestructible best in this entry, completely unstoppable and boasting what may be the best overall design of the series–from behind, you can actually see his exposed spine and bone structure, making it clear the Voorhees is more or less a murder golem at this point. The last 20 minutes are excellent, as blonde psychic Tina uses her nascent powers to battle Jason in a variety of locales, peppering him with housing nails before stringing him up with lightbulbs and setting him ablaze. It’s marred only by an overall lack of satisfying deaths (it was heavily edited, sadly) and dopey conclusion that seems out of place with the rest of the film. Other than that, the only entry in the series with a bigger body count is Part VI: Jason Lives. —Jim Vorel