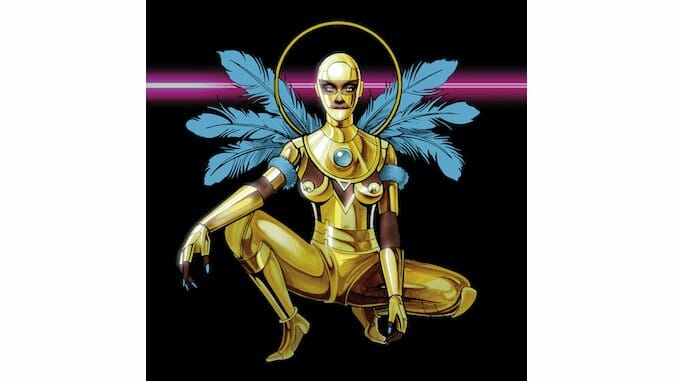

Dawn Richard Leaps and Retreads on Second Line

The longtime electronic innovator’s sixth album sees her at once expanding her palette and vision while keeping her roots firmly grounded

For someone so committed to flexing her New Orleans roots, Dawn Richard often makes music that sounds like it’s coming from an entirely different planet. On previous albums, the former Danity Kane and Dirty Money member often sang about love and life in the language of sci-fi and fantasy atop equally celestial beats. Her music likewise sounds interstellar throughout most of her sixth and newest album, Second Line: An Electro Revival (her first for an indie label, the beloved Durham institution Merge), but here, she sets an explicit goal of shouting out her homeland more than ever before.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-