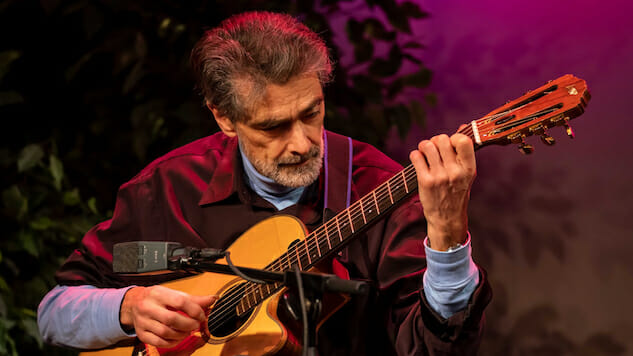

Kinloch Nelson: An Overnight Sensation That Took 50 Years

A lifelong guitarist from upstate New York gets overdue attention.

Kinloch Nelson came to his instrument of choice—the guitar—and his chosen genre—the rambling fingerpicked folk style known as American primitive—in as close to a vacuum as one could get in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s.

Around age six, he found a parlor size guitar in the coat closet of his family’s home in Massachusetts and was instantly hooked. Especially when he could lean his little head down, place his ear right next to it and feel like he was inside of the instrument. Much like sitting underneath his family’s piano while his mother practiced. He grew with the instrument, teaching himself and finding resonance with the growing folk scene that was frightening Middle America at the time. Even as he developed his own sound, Kinloch found the next catalyst in his musical evolution with an assist from his high school buddy, Carter Redd.

“I’d figured out a lot of the patterns I could do with a flat pick,” Nelson says. “But it just didn’t sound right because it was clumsy. Carter said, ‘Here, you should try fingerpicks.’ I watched him play and that’s when everything changed.”

From that pivotal moment to today, Nelson has built and sustained a remarkable career as an instrumentalist. He has expanded his repertoire considerably, studying and performing classical guitar and jazz, and holding workshops and private lessons in and around his hometown of Rochester, New York. He’s also co-founded two different guitar societies, which holds clinics and workshops for young players and presents concerts for touring musicians.

Somehow, Nelson has been able to accomplish all of this almost entirely below the radar of the music industry. And to hear him tell it, that’s been entirely by design.

“I totally avoided trying to find a record deal and becoming a personality, a national touring act kind of thing,” he says. “I saw so many gifted artists get bad record deals, especially back in the ‘60s and ‘70s when I was coming up. And I saw more than one guy go down in flames. Even a guy that I knew ultimately committed suicide because he got a bad record deal and the pressure of the big music life was too much. I just didn’t want to go down that road.”

Nelson is dipping his toes into those waters ever so gently this year thanks to a small nudge from the folks at Tompkins Square Records. The Bay Area label is getting the guitarist some long overdue attention with the release of “Partly On Time: Recordings 1968 – 1970”, a collection of tunes recorded in the studios of Dartmouth College’s radio station.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-