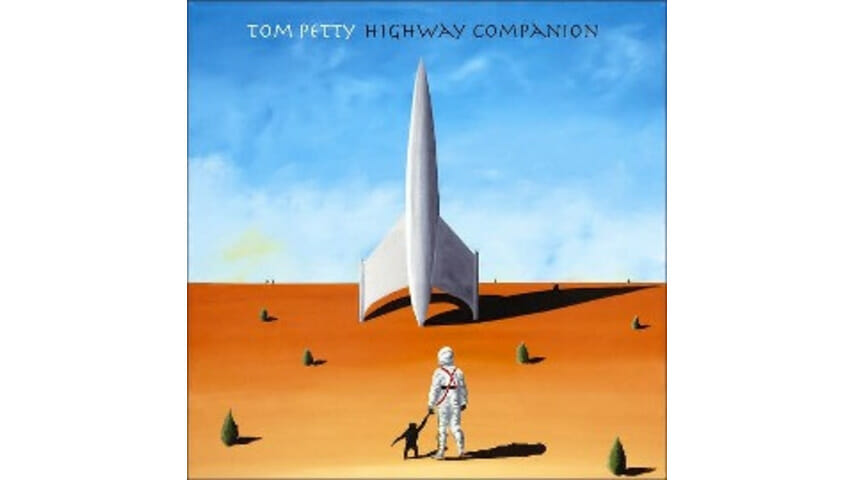

Tom Petty – Highway Companion

Bare-bones production draws attention to lackluster lyrics on Petty’s latest

“If you don’t run, you rust,” Tom Petty sings on his new album, Highway Companion. If this echo of Neil Young (and his motto, “It’s better to burn out than it is to rust”) weren’t enough, the lazy country-rock-stomp intro of “Turn This Car Around” and “This Old Town” make Petty’s new songs sound like outtakes from Young’s Harvest album. Moreover, Petty is tackling some of Young’s recent obsessions: the running-out-of-time for the baby-boomer generation and the need to clear all distractions and get back to life’s fundamentals, back to what the second track describes as “Square One.”

There’s nothing wrong with treading in another artist’s footsteps. Young has scarcely exhausted the possibilities of country-rock or of encroaching mortality. Plus, Petty has a clear-cut advantage over such role models as Young and Bob Dylan: He has the same nasal tenor that can bend notes and twist timbres into new meanings, but he has a much surer sense of pitch, so he can marry these meanings to juicy melodies.

So why is his new album so underwhelming? Because Petty has gotten away from his strength—whipping pop hooks into an emotional frenzy of harmonies—and has focused on his weakness: overly ambitious lyrics. Think of his brightest moments—“American Girl,” “Refugee,” “Even the Losers,” “The Waiting,” “Free Fallin’,” “I Won’t Back Down.” Do we remember them for their philosophical insights or for their ever-expanding swirl of vocal, guitar and keyboard harmonies?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-