Françoise Mouly & Nadja Spiegelman on RESIST!, the Women’s Rights Graphic Newspaper Released Last Weekend

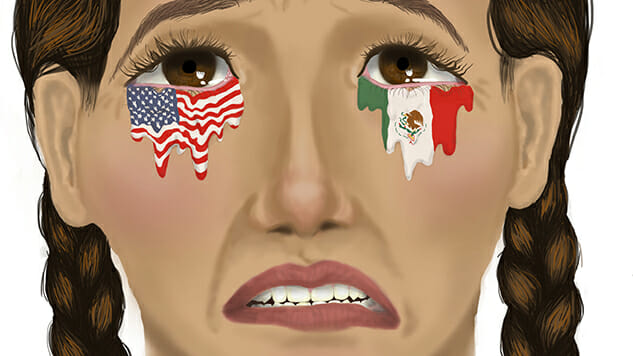

Main Art by Ciena Valenzuela-Peterson

Over the weekend, millions of women united throughout the country to protest the inauguration of President Donald Trump. From Anchorage, Alaska to Austin, Texas, hundreds of marches and demonstrations erupted across the country in what is being called the largest protest of an inauguration in American history. Showing solidarity with their American friends, family members and fellow human beings, men and women around the world took similar action—with sizable events popping up in France, England and Australia (and even a small protest in Antarctica). Over 2.5 million people came out in more than 600 different Sister Marches—local showings of solidarity with the Washington Women’s March.

At this gathering in the nation’s capital, over 30,000 copies of RESIST! were handed out. Published as a special edition of the newsprint, tabloid-sized Smoke Signal, the arts anthology features illustrations and comics from women all around the world, unified under the common theme of resisting fascism, bigotry and injustice in all its forms. The editors of the project—New Yorker art director Françoise Mouly and writer Nadja Spiegelman—were kind enough to sit down with Paste before the events of last weekend to discuss where the project came from and what they hoped it may accomplish. ![]()

Paste: Can you tell me a little bit about the project?

Françoise Mouly: It comes from Gabe Fowler, the owner of Desert Island Comics in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, who has published a tabloid called Smoke Signal for years now, which is something that he edits. It’s an old-fashioned tabloid of a size that hasn’t been seen since the underground comix. He got in touch with me right after the election, saying he wanted the next issue of Smoke Signal to be distributed at the [Women’s] March in Washington representing women’s voices. He wanted me as an editor. I mentioned it to Nadja—she’s a writer, and we’ve been working together. She jumped at the chance. So it started out as a blank check from Gabe, saying do it whichever way you want and I’ll bankroll it, distribute it. If I had been on my own, I probably would’ve contacted cartoonists and done it the old fashioned way. With Nadja, as I was doing that, we simultaneously put out an open call…

Nadja Spiegelman: It hit a nerve. The post we put on our social media went viral instantly. I think the combination of having an open call over the internet, where anyone can send something in and then have it be turned into something physical, like a newspaper, that would be handed out for free… That desire to contribute to some kind of concrete act was so powerful for people when they felt so hopeless.

Mouly: That [idea to hand RESIST! out at the march] was [Gabe Fowler’s] initial idea, and it was one of the reasons that put the whole thing into motion. I think it was why [the project] hit a nerve. It provided a deadline, and it provided a concrete action. It wasn’t just screaming into the wild. It was actually making a physical object. I think if it had been a curated slideshow on a website, it wouldn’t have been as entrancing. But making a permanent record of what we were feeling in this moment of impermanence…

Spiegelman: I think the fact that it’s free…we received so many submissions not only from artists, but an outpouring of people who wanted to donate money, who wanted to help us distribute it. It’s amazing to use the internet to create this community, grassroots movement that involves people going and handing others things physically and having an interaction. I’ve been so moved by the amount of support the project has gotten.

RESIST! Interior art by Ciena Valenzuela-Peterson

Paste: What steps, if any, did you take to make sure certain groups of women’s voices—whether it’s women of color, Muslim women, lower-income women—were represented in this collection?

Spiegelman: I would say that, for me, more than with most projects, diversity was a priority and one of the values that I was looking for in the work. We were hearing such a strong collective voice from the thousands of submissions that came in, but in order to translate that as clearly as possible, we needed it to be as multi-layered as possible. And I think what makes our newspaper of resistance is for it to be diverse.

Mouly: The quantity of work that was sent to us, the goodwill, the sheer number—because of how open it was, because there was no entry fee, people could send us as many images. We made those decisions the first day, that we weren’t going to limit anything. It let people take chances. And one thing we saw: we were posting work on the website, and it encouraged more. The more pieces of work we were posting, the more individual pieces came in.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-