White Bird in a Blizzard

White Bird in a Blizzard is a mystery story, but not the mystery you’re expecting. Set in motion by the disappearance of a teenage girl’s mother, filmmaker Gregg Araki’s latest is only sporadically concerned about the parent’s whereabouts. Instead, it focuses on the young woman left behind, in the process delivering a rather thoughtful study of adolescence, budding female sexuality and the horrifying realization every child goes through about her parents: At one point, they were people, too.

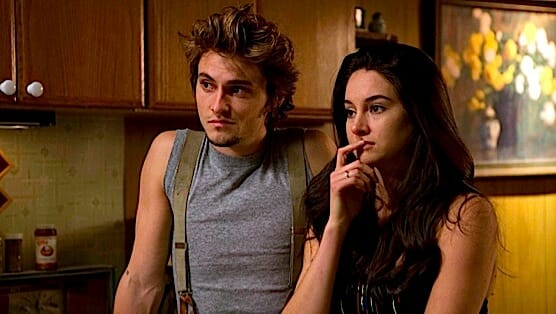

Based on Laura Kasischke’s 1999 novel, White Bird in a Blizzard is set in Southern California suburbia in the late 1980s. Shailene Woodley plays Kat, who’s about a year from graduating high school when her mother goes missing. Even before then, though, Eve (Eva Green) was acting strangely, sleeping on her daughter’s bed in the middle of the day and finding her way into the liquor cabinet, expressing bitter disappointment that she married the ineffectual office drone Brock (Christopher Meloni). When Eve vanishes, Kat and Brock aren’t entirely surprised: They both privately conclude that she walked out on them to go find a better life somewhere. Maybe if Kat were braver, she’d do the same thing.

With such a setup, the film raises expectations that the plot will follow some sort of whodunit narrative as the police look for clues into Eve’s disappearance. (Was she kidnapped? Murdered? In hiding?) But Araki (Mysterious Skin) has no interest in our expectations. As envisioned by Araki, Eve is a permanent specter, a ghostly presence in Kat’s life even when she was around. Green plays the character with more than a touch of camp, giving Eve a boozy, bored-housewife vibe that suggests it’s less a realistic portrait than the exaggerated image her daughter had of her.

That suspicion is backed by Araki and cinematographer Sandra Valde-Hansen’s dreamlike tone to the proceedings. Even when Kat isn’t waking up from visions of walking through snowstorms, White Bird in a Blizzard seems adrift in the character’s teen-angst disillusionment, and the film has a bittersweet, melancholy air that borders on the artificial. At times, Araki seems to be making an ersatz ’80s teen drama that’s a knowing homage to actual ’80s teen dramas, but the emotions sting in such a way that White Bird in a Blizzard transcends pastiche.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-