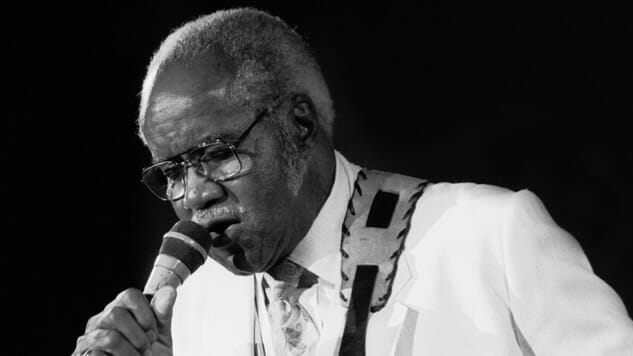

The Curmudgeon: Pops Staples and the Great Variety of African-American Music

Almost no one talks about European-American music as if it were all one thing. Few folks work from the assumption that John Adams’ symphonies, Stephen Sondheim’s show tunes, Kurt Cobain’s grunge, Paul Simon’s folk-rock, Britney Spears’ pop and Willie Nelson’s country are part of one big genre. Yet people talk about African-American music like that all the time—and not just outsiders. Many of that music’s insiders like to talk as if “we’re all in this together.”

Given America’s cultural history, perhaps it’s natural that black musicians resist anything that smells like a divide-and-conquer strategy. But such resistance makes it difficult to appreciate the amazing variety of African-American music. Or to understand the blues-vs.-gospel tension that informs many of the music’s greatest moments. Or to get a grasp on the profound differences between the sound of the Civil Rights Era and the musics that preceded and followed it. Or to fathom such outliers as Sun Ra, Anthony Braxton, Oscar Brown Jr., Jimi Hendrix and Rhiannon Giddens. Or to properly evaluate Roebuck “Pops” Staples.

For the reflexive attempt to fit Pops into the mainstream of gospel or R&B only diminishes the strangeness and power of this musician. He played guitar like no one else—not very fast, not with a lot of notes and not with a lot of range, but as if each string on his instrument had been snipped and retied into a barbed-wire strand. Unhurried and uncluttered, his guitar phrases used their flatted thirds and sevenths to evoke both brutal treatment and resilient optimism.

He sang much the same way: making the most of a few, laconic notes. Perhaps his closest analogue was Johnny Cash, whose voice was similarly bottled up in a shortened range but who likewise sang with the nerve-jangling authority of an Old Testament prophet.

The economy and patience of Pops Staples’ music reflects another source of the diversity in African-American music: the tension between town and the country. Both his singing and his guitar playing are products of the Mississippi farmland where he grew up. Much of his early repertoire came from the pre-1920 black community, which was as overwhelmingly rural as today’s black community is overwhelmingly urban.

Though he moved to Chicago and raised his son and daughters there, Pops never let go of that essential “country” quality in his music—the sound of an environment where a quiet note could carry farther through the silent night, where there was no hurry to get to the next song and where death was only a failed crop away.

You can appreciate the continuity of Pops’ influence over the course of the Staple Singers’ career on the new four-CD, 80-track box set, Faith & Grace: A Family Journey, 1953-1976, the first anthology to collect songs from most of the labels the Staples recorded for during those years: Royal, United, Savoy, Vee-Jay, Riverside, D-Town, Epic, Stax and Warner Bros. Even as the repertoire shifted from traditional spirituals to new songs written in the spirit of the Civil Rights movement, the echo of Mississippi’s piney woods in Pops’ voice and guitar was a constant.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-