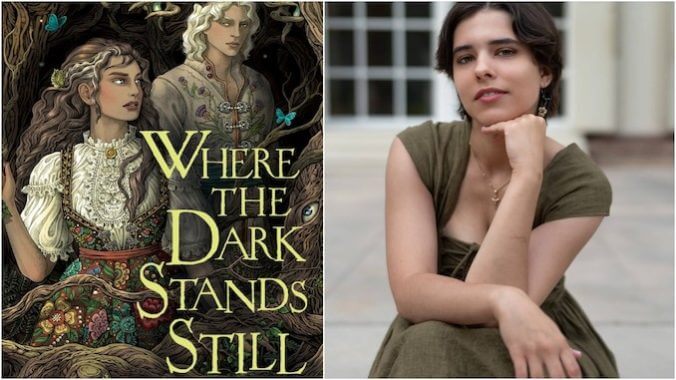

Reimagining Folklore: The Polish Inspiration in A.B. Poranek’s Where the Dark Stands Still

You know the story. A traveler goes into the woods, sees a beautiful flower growing from a bush near a mysterious manor, and is greeted by the monster that dwells within. But this isn’t “Beauty and the Beast.” What lives in the woods of Where the Dark Stands Still by A.B. Poranek is something much more dangerous than a cursed prince, and the girl who agrees to work for him for a year is far from helpless. Instead, Liska is a girl trying to get rid of her own curse—a magic that she doesn’t want, and seems only to harm those around her—and the Leszy is the guardian demon of the woods. Despite what everyone knows about demons, Liska makes a bargain, and in doing so discovers how much of what everyone knows is utterly wrong.

Where the Dark Stands Still has a very fairy tale feel: the qualities of the young person entering the woods and encountering greater magical forces is reminiscent of many familiar stories. The magical manor that feels almost like a living thing itself evokes not just the enchanted house of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast (admittedly a film Poranek adores), but also the nearly-sentient house on chicken legs of Baba Yaga. Secrets hidden behind locked doorways might offer that same creepy feeling of all not being right that readers encounter in “Bluebeard.” But more than any of these tales, Where the Dark Stands Still draws on Polish folklore, the same stories that Poranek grew up with. When asked about the comparison to other European fairy tales, Poranek acknowledges, “There are similar elements: the flower, the library, the monstrous boy, but they were never intentional—these are just elements I’ve always enjoyed in stories.… I think a lot of fairytales tend to echo each other, since we always gravitate towards certain morals, like seeing the beauty within or helping those in need.”

In the story, Liska seeks a mythical fern flower, one that will grant a single wish. There’s nothing Liska wants more than just to fit in, and fitting in means getting rid of her magic. If only she were normal, she would have an intact family, and a friend who still cared for her like a sister. But something truly awful has happened, and it has driven Liska to this one last hope. However, finding the flower means navigating the Driada, a spirit wood where the demon warden, the Leszy, has trapped demons who will harm human travelers. The Leszy defends the mortals within the Driada’s boundaries, and they offer him tithes for the service. But he’s still a demon—or so Liska believes—which makes him dangerous, and not to be trusted. When the Leszy guides her to the fern flower in the guise of a white stag, he makes her a bargain: she must serve him for a year, and he will grant her wish. She knows it’s a trap, but she sees no better alternative. After all, what is a year when she will have the rest of her life without magic?

But as Liska serves the Leszy, who seeks to free her magic away from where she has locked it, she begins to realize how little she understands about the world beyond the borders of her small village. In order to help the Leszy keep humans safe, she must open herself up to the possibility that her magic might be useful. And once she does, she has to confront that perhaps she has never really considered what she wanted in life, only the life that was planned for her. Surrounded by a delightful cast of supernatural characters—a skrzat house spirit, a czarownik who has used magic for a lifetime, a siren-like rusalka, and more—Liska develops the vision of what the world should be, the duty of keeping others safe from harm, and the understanding that the wood must always have a warden.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-