Exclusive: First Second’s Idle Days Promises Beauty, Anxiety & Ghosts in WWII Canada

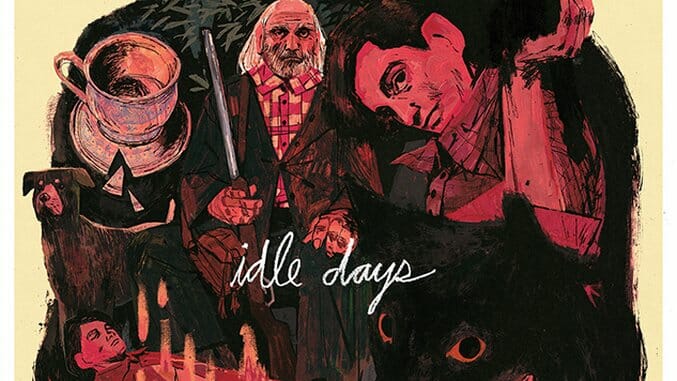

Entering its 10th year of operations this month, publisher First Second is expanding into the future by exploring the past with two new projects that sound hauntingly cool. Paste broke news on Antoine Revoy’s The Playground roughly a year ago, and now the imprint is prepping Idle Days from debut graphic novelists Thomas Desaulniers Brousseau and Simon Leclerc. This new tale follows Jerome, a World War II deserter holed up with his grandfather in a decaying house surrounded by an ominous forest. Isolated and increasingly anxious, Jerome soon encounters a succession of surreal threats including “a dead woman, alcohol smugglers, a witch, [and] a black cat” as his reality deteriorates.

Writer Brousseau helms the webcomic Boire du mercure while Leclerc is a storyboard/concept artist for many a secret video game. Judging by the sunrise-colored sample pages below, Idle Days will ooze atmosphere and texture with a scratchy, densely-detailed style reminiscent of Dave McKean’s and Bill Sienkiewicz’ work. Paste emailed with both creators from their home in Montreal to discover more about this enigmatic new project and how it channels personal history, style and claustrophobia with passion and finesse.![]()

Paste: Simon and Thomas, thank you kindly for taking the time to answer some questions. This is a huge long-form debut project for the both of you. Can you describe its inception and how your collaboration began?

Thomas Desaulniers Brousseau: Thanks for having us! We’re very glad for this opportunity to be discussing our work.

Simon Leclerc: Indeed, such a pleasure! So yes: I worked on my first comic in 2010 or 2011, which was published sometime in 2012, and then I went to study animation abroad at the California Institute of the Arts for a year. At that time, I knew that when I’d come back to Montreal I would want to work on a graphic novel project again, and I knew Thomas was writing short stories on his side. So I asked him to write a brief for a story that I could illustrate, and we built a pitch together when I returned. We knew our project was a tough sell to publishers, because we planned it as a 200-ish page fully colored book—but we planned it from the start as a book we’d want to do, not a book we’d want to sell. I posted some excerpts from the pitch on my Tumblr, and soon enough, First Second’s Senior Editor Calista Brill emailed me. And then I got pretty excited, because so many authors I admire are published there. And then I guess they trusted our pitch enough to sign two unknown authors, and now here we are!

Brousseau: It was such a great surprise. We were initially pitching the project to French publishers, and then when Calista contacted Simon, I translated everything in a rush and had like three people read it over. A few months later, Simon asks me out of the blue how well I could write in English, and I said: “Not too bad I think, why?” Then he told me First Second wanted to sign us and we went pretty crazy. I’ve been winging it since then.

Simon and I have known each other since high school, and though we played in a joke-band together back then, we didn’t talk much and were never really close. The summer before he left for California, he took the room of one of my roommates who was moving out and we got to know each other a bit more. I don’t think he had ever read anything I was writing, and I only knew his work from what little he showed people, which wasn’t much since he is a pretty secretive person. Sometime around the moment he offered that we collaborate on a graphic novel, he also mentioned his plan to move back in with us. Life was pushing us together for reasons other than this project, and although our work has been very compartmented in a way—him giving very little input on the story and me having complete confidence in his work—my initial idea for the story evolved in surprising directions. Although it is a very personal story, I see a lot of him in it, too.

Idle Days Interior Art by Simon Leclerc

Paste: This project takes place in your home country of Canada (maybe Montreal, too?), and lead character, Jerome, finds it both haunting and isolating. How much does Jerome’s perspective of the country reflect your own, or is his reflection more a result of his situation?

Brousseau: I think the story is drawn from more personal considerations than, say, national ones. Although I have spent most of my adult life there, this is not a story about Montreal but about the forest, and about a very specific place that has marked my imagination since childhood. I have a pretty strong fascination with the woods, but the idea of living there day after day is also quite far from what I’ve known my whole life; I don’t know that I could handle it as well as Maurice, the grandfather, seems to. That being said, maybe there is something to the fact that this is a story that takes place in some isolated place in the middle of nowhere, steps from the U.S. border, and that it verges on horror, ha!

Leclerc: Jerome, being a deserter, finds himself forced to live in his grandfather’s house, isolated in the woods nearby. The story then unfolds around that house; the forced reclusiveness gets Jerome interested in the previous generations of the house owners and their mysterious and tragic fates that weirdly relate to his. Along the way, the forest unveils its haunting characters: a dead woman, alcohol smugglers, a witch, a black cat, all while Jerome has to deal with his grumpy grandfather!

Paste: World War II is arguably considered the most morally-justified of all the major historical wars. What attracted you to exploring the perspective of a deserter?

Brousseau: Well I wouldn’t say that it’s really what I set out to do. I needed something that would keep the character stranded in the forest, and him being a deserter was mostly a convenient device. But once I chose to do that, I didn’t really question the morality of it. Although the vast majority of Canadians believed the war to be necessary and many enrolled of their own will, the people accepted it against the promise that there would be no conscription, at least for overseas service. French Canadians were particularly opposed to it, judging as in the case of the First World War that it was chiefly a European conflict, and particularly that of the United Kingdom, their historical oppressor. The Canadian Forces were also an organization where French-speakers were heavily marginalized… and I am cutting corners right now, but the bottom line is that the opinion of the majority of Quebecers contrasted with that of the rest of Canadians. And when the Government reneged its promise and imposed conscription, there was generalized dissent here. Desertion, or simply dodging the draft, was very frequent—the mayor of Montreal was actually sent to jail for urging people to ignore the registration—and these young “insoumis” usually had the approval of their community. The deserter/conscientious objector is a sort of mythical figure in Quebec, and speaking to people around me, I realized that most have a family story to tell on the matter.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-thumb-230x237-423120.jpg)