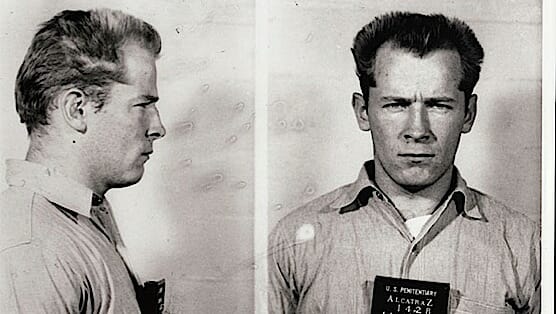

Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger

In all of the hubbub surrounding the capture, indictment and trial of James J. “Whitey” Bulger, two kinds of reporting occurred: the responsible kind that took great pains to chronicle the fracas’ every minute detail, and the sensationalist kind that cared more about the exchange of expletives between Bulger and his longtime confidant, Kevin Weeks, in the middle of federal court. Of these, Joe Berlinger’s Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger assuredly falls into the former category, but that’s not necessarily to say that it’s a great piece of journalism, or even a particularly good film. Berlinger’s work here is impressively comprehensive, and the volume of information on the case is plentiful. It’s the execution that’s frustratingly lacking.

Which is to say that Whitey isn’t a particularly bad film, either, just a disheveled, disorganized, ugly and pointedly non-cinematic one. This subject has been covered in print and at length before and since FBI agents rooted Bulger out of his Santa Monica apartment and charged him with murder most foul, conspiracy to murder most foul, narcotics distribution, extortion, and money laundering; Whitey, if anything, is just an extension of that coverage, put on the big screen for our elucidation and edutainment. Berlinger doesn’t have a new angle on the Bulger mythos, his Robin Hood persona, or what his past crimes even mean in today’s Boston.

He does, however, have some sharp thorns to stick in the side of the law enforcement agencies that allowed Bulger to get away scot-free for several flavors of bad behavior. Whitey makes a meal of the corruption that, in essence, enabled Bulger’s criminal tendencies and helped him maintain a stranglehold on Boston for years. The question is posed, in both more and less explicit terms, as to whether Bulger is the bigger crook, or if it’s really the FBI. After all, the Feds are supposed to be the ones putting the psychos behind bars, something Berlinger depicts through news clippings of the Bureau’s successful takedown of the Angiulo crime syndicate prior to Whitey’s rise to prominence.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-